Ngugi Wa Thiongo: Why Kenya Needs Him

|

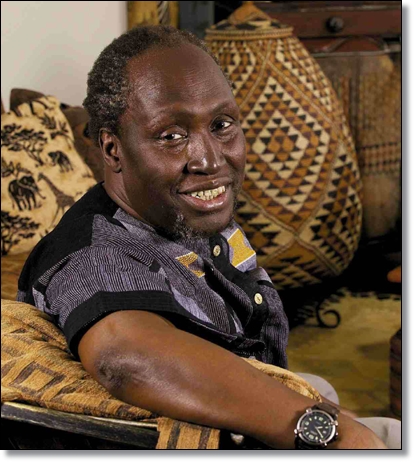

| Professor Ngugi wa Thiong’o P. Courtesy |

It seems that his American hosts also have a problem with him. Late last year, the itinerant Kenyan professor was embarrassed at the San Francisco, a penthouse guest at the Vitale Hotel, for taking a newspaper from the reception and seat on the terrace of the Hotel’s restaurant enjoying the view of Embarcadero, the harbour-front.The management questioned Ngugi, to explain, among other things, if he was a “guest” since the terrace and the newspapers were strictly for guests.

In another scenario, a white guy in New Jersey who found professor and his wife waiting in line to use an ATM, demanded to go ahead of them because they were “cashing a welfare cheque.” Being black made him assume Ngugi and the wife were recipients of monetary handouts from the government. An undercover police officer who happened to be there stopped what was turning into an ugly confrontation.

Professor Ngugi has lived and worked abroad since early nineteen eighties, when he defected from Kenya due to President Moi’s brutality and dictatorship. Aged 74 now, he is professor of English and Comparative Literature and Director of the International Centre for Writing and Translation, at the University of California, Irvine. Ngugi is also a visiting Associate Professor of English and African Studies at Northwestern University and an Honorary Member of American Academy of Letters. He is also a novelist, essayist, playwright, journalist, editor, academic and social activist.

With that kind of vitae, and given that America would stock special data on such an important luminary, was it a mistake that the San Francisco, Vitale Hotel management could treat him with such brutality, or the host country is now tired with him?

However, after this humiliation, the CEO of Joie de Vivre Hospitality, the parent company owner of the hotel, published a public apology on 450 dollar worth of space, and in negotiations with Priority Africa Network, agreed to conduct diversity re-education of his employees. He visited Ngugi in Irvine, South California, to apologise. In addition, he paid 5000 dollars to a grassroots organisation for anti-racist activism in the Bay area.

But what was Ngugi thinking about that night in his hotel room? That his racist attacks were a mistake? That these were ignorant hotel attendants? Are his American hosts already bored with him? Has he misused the wide American democratic space by discussing Western heresies? Or is America changing into a vast anti-democratic conspiracy?

Despite my criticism of Ngugi, I love his audacity and respect fact that he has always carried a Kenyan passport. But is it not time he came home and spent his remaining years on some tangible research activity on Kenyan soil, especially when you consider that he has spent barely a year continuously in Kenya since 1983!? And even then only from the safety of taking a “sabbatical” from his ‘lucrative’ job in the USA.

His book Decolonising the Mind is both an explanation of how he came to write in Gikuyu, as well as an exhortation for African writers to embrace their native tongues in their art. Ngugi claims that the foreign languages most African authors write in like French and English are the languages of the imperialists that were relatively imposed on them. However, Ngugi neither considers Arabic nor Swahili in the same light. Ngugi makes a good case for the obvious point: that the relation of Africans to those imposed languages is very different from that which the same Africans have to the native languages they speak at home.

Ngugi rightly decries the destructive educational focus that embraced essentially only foreign mentality; not only foreign in language, but also in culture. Foreign language and literature were taking us further and further away from ourselves to other selves; from our world to other worlds. He reiterates the need to create literature that conveyed the true African experience - from the perspective of the local, not the visitor or outsider. The local language is an integral part of conveying that experience, often because much of local tradition has been preserved in that language for instance, in the songs and stories that have been passed down through oral tradition - orature -that Ngugi values.

Ngugi's basic arguments are largely convincing. His personal experiences make the entire book an interesting read. In the end he maintains that it is manifestly absurd to talk of African poetry in English, French or Portuguese. Afro-European poetry, yes; but not to be confused with African poetry which is the poetry composed by Africans in their languages.

Ngugi is right to say that it is important to reach an audience in the language of its heritage but not in the language of the former imperialists. But it is time Ngugi – a Pan-African crusader to uphold his teaching of decolonizing the mind and return back to his motherland where he can still offer his intellect in any University.

However, it does not imply that when he begins to work here, at home, Kenyans will be able to understand him. But, at least, he will have made some memorable contribution to his motherland. Ngugi has spent his life educating the world. Why not come home and summarise all that effort, as he sips his gin and tonic, sitting on one of the benches in the Kenya National Theatre! East or West, home will always be the best.

By Okwaro Oscar Plato

The author is a political analyst with Quadz Consulting Africa. The views expressed are solely of the author and do not reflect those of the organization.