Emerging Legislatures in Africa: Challenges and Opportunities

Role of Parliamentarians

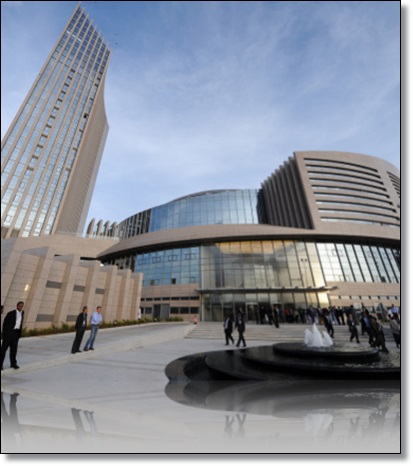

AU Headquarters in Ethiopia

As parliamentarians, we must always be alert to the possibility of bottlenecks in our procedures. We must be constantly examining our procedures to see how we can improve them. I should point out that in Ireland, the lower House, the Dail, is the more powerful, the same as the House of Commons in the UK. I know that the system in Nigeria is different, based on the American system rather than the British.

The Programme for Government noted that the fundamental goals of a properly functioning Dail include to: legislate; represent the people on issues of national concern; ensure more effective financial scrutiny, and to hold the executive to account. These functions apply to almost any parliament.

The Government undertook, in its programme, to institute a number of short-term and urgent reforms to make the Dail fit for purpose. Some of these include enhancing the role of committees; providing that the Government publish the general scheme of a Bill so that Parliamentary Committees can debate and hold hearings on the proposed legislation at an early stage; increasing sitting days; revamping our adjournment debate system, to be renamed the topical issues debate, so that it will be taken in the middle of the day and a minimum of five topical issues covered; and establishing a petition system to be managed by a specific Committee that will investigate and report on petitions which raise issues warranting attention.

The African Context

We hear a lot about “Emerging Africa,” which for many paints a picture of a continent with many diverse countries all emerging simultaneously from a history of underdevelopment to benefit from more recent economic stability and global trade. This image is of course, too simple. Africa is not one entity when it comes to either development or trade. African countries have different histories, different challenges and of course different opportunities.

In future, African countries will also increasingly compete with each other for trading partners and for inward investment. One would expect that the countries that perform best are those that have the strongest parliaments to create legislation and a robust civil society to hold government to account for decisions made on behalf of their citizens.

In many cases in Africa, new trading relationships are based on the natural resource endowment of individual countries. International initiatives have been put in place to safeguard these resources and to force compliance by investors in terms of transparency. I learned on a trip to Ghana last month that the mineral sector is leading the way in terms of best practice.

Some of the initiatives are voluntary while others involve self-regulation by private companies. Self-regulation by investors is certainly to be welcomed. It is however not always a guarantee of best practice. Large companies with significant investments will see the value of compliance. Where legislation is vague or enforcement is weak, poor practice will inevitably arise as some will attempt to cut corners. Smaller companies, including local and informal businesses often feed into the supply chain of larger concerns but are not accountable to the same extent. We can all think of examples where artisans are involved in mining practice that is both dangerous to the individuals as well as potentially causing long term damage to the environment.

In the natural resource sector, good legislation should be in the interests of all parties allowing the compliant companies continued access to resources while allowing the citizens of the country a fair return on their own resources. Parliamentarians have a role in shaping and overseeing this legislation. It is a necessary and important role that will ultimately reduce inequality, promote more even growth and development, encourage better recovery of revenue and reduce inequality.

There is always a gap between the ability to enact good legislation and the power to enforce it. Many countries have strong legislation without the ability to monitor and police its implementation. We can think of many examples across Africa where legislation alone is not an adequate response. One example is the long coast lines in Africa which challenge governments to patrol piracy, smuggling and illegal and environmentally damaging practice. In many of these cases, we have seen success when we have developed strong partnership between national and international actors.

Examples from Ireland

The Irish case study is one where a period of sustainable economic growth was overtaken by growth based on a construction and property bubble, recklessly fuelled by the banking sector. On joining the Eurozone, Irish banks gained increased access to wholesale funding at a relatively low cost. Irish banks increasingly channelled that funding into an over-heating property sector to maximise profits – with little thought for diversification or potential risk. Government policies and statements tended to support this expansionary path and the associated risks were too often undetected, misjudged or downplayed.

When the crisis finally came – inevitable in retrospect – the crash of the property market left Ireland’s banking system as a whole completely exposed. There has been considerable discussion and controversy within Ireland on how that situation was handled as it emerged. It is clear that at that point there were no options left except very painful ones.

To preserve the stability of Ireland’s financial system, an amount equal to 40% of our GDP has been committed to support our banks. That is to say nothing of the sudden gap which opened up for the funding of vital State services and of the huge personal debts accumulated by ordinary people who had invested in their homes during the bubble.

Three years ago, it became clear that Ireland could not borrow on the international markets at sustainable rates, and the assistance of the European Commission and the IMF was necessary. We are set to emerge from this programme of assistance next month having completed some 230 separate actions on which the assistance was conditioned.

It is important at this stage to note that the overall Irish story is a successful one. In Ireland we are a stronger, leaner and certainly smarter economy. Ireland is on track to be the first country in the Eurozone to exit an EU/IMF Programme of assistance. The Irish economy is forecast to see modest economic growth of 0.2% in 2013 – our third straight year of GDP growth. An acceleration in growth rates to 2.0% is expected in 2014.

Exports have driven our recovery. Total exports are 16% higher now in nominal terms than the pre-crisis peak in 2007. Our balance of payments is expected to remain in surplus for the fourth year in a row in 2013.

Last month, I travelled to Ghana with the Joint Committee on Foreign Affairs and Trade. The objective of the mission was to consult with a range of Ghanaians on the challenges arising from economic growth and to identify if there were any parallels with the Irish experience. The Committee met with Dr Ed Brown and his team at the Africa Centre for Economic Transformation. Dr Brown provided a very interesting overview of the challenges which many African countries face including a number of recent developments in Ghana itself.

Ghana, one of Africa’s fastest growing democracies is challenged by a number of issues that have parallels in Ireland. Last year, before the elections in Ghana, public sector salaries grew to an unsustainable level due to an increase in salaries for the 600,000 public servants and the creation of 45 new districts.

In Ireland, we experienced an increase in public sector salaries to match those of the booming private sector. While this may have been justifiable in terms of retaining senior managers in the public service, the overall cost was ultimately unsustainable. One part of the necessary reforms after our boom period has been a real cut in public sector wages resulting in a reduction in take home pay for the average civil servant of more than 20% as well as further levies and tax increases. Some of these measures are short term others are longer term. I believe it is fair to say that a more modest and measured approach to public salaries would have been wise in hindsight.

Identification of bottlenecks and constraints

As elected government officials we know what the needs of our constituencies are. We probably are less sensitive to how others see us. As public representatives we all believe that we represent the best constituencies and that we must work within our mandate to try to do the best for our citizens. However perceptions are a key challenge in terms of attracting investment. Many African countries have a troubled history as indeed we have had on the island of Ireland. It takes a lot of reassurance for an investor to enter a market when their impressions are formed by international media that, by nature, focus on the most tragic stories.

While these perceptions may not be in the hands of legislatures, it is important to note the point in passing. Other perceptions are very clearly within this mandate. As many growing economies are emerging from a history of weak governance associated with poor performance and weak and corrupt regimes, it is essential not only to note improvements in terms of reducing opportunities for rent seeking and graft but to underline these developments with concrete steps in terms of legislation.

Role of Government and Parliaments

Government must be seen to act on cases of corruption. Guilty parties must be brought to account and transparency in the legal system is necessary to build public confidence. Oversight of these processes is a necessary role for parliamentarians.

In many African countries, first impressions often relate to ease of travel. This includes the ability to acquire a visa without delay and to pass through airports without undue difficulties. Where visitors experience difficulties at these early stages, they will naturally assume that other parts of government work the same way.

Transaction costs are usually divided into two broad categories, known and hidden costs. The former are predictable and can be costed into any travel plans. The latter are not transparent and, more often than not, take the form of cash payments which are presented as optional for improved services. Such grey areas provide room for confusion and abuse.

In Ireland we have adopted online processing for services that we believe contribute to improved efficiency. The same paperless procedures can also remove opportunities for rent seeking by opportunistic officials.

I know that Irish companies are working across Africa in the area of financial services to develop new systems that will not only improve efficiency but also reduce opportunism.

Taxation

This is an important area for all Emerging legislatures in Africa. Domestic revenue collection is directly related to the size of the formal economy. In many African countries the majority of workers remain in the informal economy and are effectively outside of the tax net. Increasing the tax net is a challenge which will essentially involve actions by government to convince the business sector that there are long term advantages in formalising business. The challenge will vary from country to country but there are many positive cases across Africa.

In terms of international tax challenges these cannot be addressed at national level alone. Ireland is participating constructively and purposefully in international fora in relation to these matters, in particular we are active in the work of the EU and the OECD.

By Mr. Pat Breen

Chairman of the Joint Committee on Foreign Affairs and Trade, Ireland.(Excerpts).