Dealing With Militants: The Case of Kenya and the Phillipines

|

In South East Asia, the Philippine media is rife with debate on the outcome of a botched covert police operation in the country’s restive island of Mindanao that left 67 people dead, 44 of whom were members of the Philippine National Police Special Action Force (PNP-SAF), an elite police commando group. Operation Exodus was mooted as a covert mission to capture known terrorists Zulkifli Bin Hir, alias Marwan and his accomplice, Abdul Basit Usman. Blacklisted by the FBI as a wanted Jihadist connected with the 2002 Bali, Indonesia bombing, Marwan was the alleged leader of the Kumpulan Mujahidin Malaysia, the central command of the Al Qaeda linked and Indonesia based Jemaah Islamiyah. He had a bounty of US$5 million and thus the priority to neutralize Marwan in his hideout in Mamasapano, a quit village in far flung Maguindanao located in the southern part of the Philippine archipelago.

On 25th January, 2015, the Operation was rolled out that saw the eventual killing of Marwan. However on their retreat back from the site, the SAF commandos encountered guerrillas belonging to the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF) which saw 44 members of the PNP-SAF members lying dead after the encounter. This was not the first operation in pursuit of Marwan. Nine such operations had been attempted since 2010. Five were aborted while the other 4 had failed.

On her part, Kenya’s involvement in Somalia is marked by “Operation Linda Nchi” (Operation Protect the Country] that was launched on 11th October, 2011. This is the largest military operation since independence in 1963 meant to sweep through areas of Southern Somalia controlled by the extremist Islamist group. On a mission to protect the nation's "territorial integrity," Kenyan forces are attempting to secure the northern border with Somalia, an unstable region where the killing and abduction of Western tourists, aid workers, and local Kenyans has made news. The escalation in murder of Westerners has been an important catalyst, but not the sole reason for this armed intervention.

In November of 2011, the Kenyan government agreed to have its forces re-hatted under the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) and were therefore formally integrated into AMISOM on February 22, 2012 after the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 2036. Thus in efforts to keep her borders safe from extremists, Kenya got sucked into the ‘Somalia problem.’ In retaliation to Kenya’s troop presence in Somalia, the militant al-Shabaab vowed to disrupt the peace in Kenya. In November 2014, elements of the al-Shabaab ambushed a bus in Mandera, coincidentally near the Somali Border with Kenya, and killed 28 non-Muslim passengers. This was followed by another attack on a group of quarry workers in the village of Kormey, near the Somali border, killing 68 of them. Al-Shabaab said the attack was retaliation for mosque raids that Kenyan security forces carried out in November of 2014 to weed out extremists.

The Garissa University College attack is the biggest assault by the militants so far which has raised public concern over the security apparatus of the country in protecting the citizenry. Indeed Richard Downie, a fellow and deputy director of the Africa Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C. warned in his 2011 article entitled ‘Kenya’s Military Operation in Somalia’ of civilian casualties likely to intensify Somali hostility to Kenya. Recent events in both Kenya and the Philippines in the quest to contain militants within its borders have revealed some uncanny shared experiences.

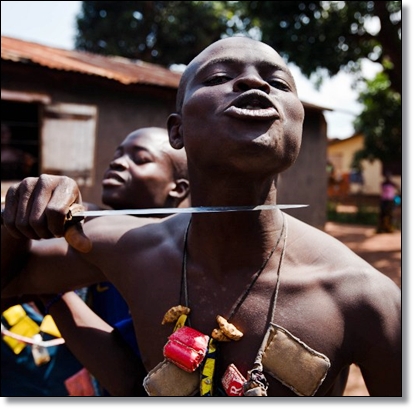

Like Somalia, Mindanao in the Philippines is a restive predominantly Muslim enclave and a terrorist haven. According to a 2008 US State Department report, Philippine government has little control in the Sulu archipelago and the island of Mindanao. The government has also had trouble combating resentment among the local Muslim minority regarding policies of the central government. As a result, the Philippines is home to a number of militant groups, of which the Abu Sayyaf Group, the Communist Party of the Philippines/New People’s Army (NPA), and Jemaah Islamiyah are listed as terrorist organizations that are active in the Philippines. Adding Khalifa Islamiya Mindanao to this list may not come as a surprise.

The Philippine government has taken significant steps to combat terrorism, but terrorists continue to use the country as a base to organize, raise funds, train, and operate. The Philippines is therefore under perpetual threat from Islamic radicals. The central government in Manila is in the quest to end hostilities with the major rebel group in Mindanao, the MILF, starting with the signing of ceasefire guidelines to prevent any truce violations in March 2013. In effect, both sides agreed to a joint Coordinating Committee on the Cessation of Hostilities (CCCH) to prevent any truce violations that could endanger an on-going peace process effort dubbed the ‘Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro’ that will see and the Moro rebels ending their demand for a separate state in exchange for broader autonomy in Mindanao. But the Philippine government still has to deal with other militant groups hell bent in disrupting any peaceful effort on the ‘Mindanao Question.’

This is no different to what Kenya is experiencing with the Somali based militant groups across the administrative border. Historically, the central government has had to deal with secessionists who sought to sway the predominantly Somali North Eastern Province towards the cause for a ‘Greater Somalia.’ This attempt lead to the 5 year ‘Shifta War’ (1963–1967) that culminated in a ceasefire agreement signed by then Prime Minister of the Somali Republic, Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal. However, the violence in Kenya deteriorated into disorganised banditry, with occasional episodes of secessionist agitation, for the next several decades. Today, the vast semi-arid area is a haven for al-Shabaab militants and other bandits.

Like the Philippines, Kenya does not have the capability, military or financial, to be sustain its efforts securing its porous borders and citizen security adequately. Peace efforts are the available options for both countries. For the Philippines, a negotiated ceasefire agreement and efforts towards autonomy on the part of the Moro is on the table, while for Kenya, calls are made to recall its soldiers from their peacekeeping duty under AMISOM. However, the cases in Mamasapano and Garissa have raised questions on such peaceful efforts.

Government critics in the Philippines are arguing for the government to stop negotiations with the MILF by passing the Bagsamoro Basic Law (BBL), while in Kenya, calls are being made to close the Daadab refugee camp in order to stem entry of insurgents under the guise of being refugees from across the border or turning the camp into a militant recruiting base. At the same time, questions have been raised in both country contexts on the competency of security organs in coordinating and checking militant attacks. The brutal manner in which the 44 SAF members were killed coupled with emerging allegations of lack of coordination on the part of the Philippine central government not only to retrieve the trapped soldiers, but also tin he lack of coordination between the police and the army on the ground, left a country shell-shocked and in need for answers. This event has in turn dented the President’s image with poll surveys showing trust and approval ratings at the lowest since the President’s assumption to office.

President Aquino has been on the receiving end ever since the Mamasapano incident; from his inability to receive the flown remains of the commandos in Manila, to alleged lack leadership on the matter and instead laying blame on now sacked Special Action Force (SAF) director Getulio Napeñas for the bloody results of the Mamasapano clash. President Aquino indeed took time to meet with individual families on two occasions and to oversee government assistance to the bereaved families but where some emerging reports indicate his inability to amicably address concerns of some family members who sought immediate answers from the President about the botched mission.

On this part too, President Kenyatta’s ratings have not been rosy. Polls show that the President’s approval rating dropped by 10 per cent following the Garissa University College massacre attributed in large to his administration's inability to adequately respond to the campus attack. Like the sacking of SAF director Getulio Napeñas for Mamasapano mishap, President Kenyatta had seen the resignation of Police Chief David Kimaiyo and that of his Interior Cabinet Secretary following the quarry attack in Kormey well before the attack in Garissa happened. The latest incident in Garissa has put the spotlight on Kenya’s internal security system again under the directorship of new Interior Cabinet Secretary Joseph Nkaissery and the new Inspector General of Police Joseph Boinett and President Kenyatta as Commander in Chief.

President Kenyatta faced criticism on his inability to make time to visit the grieving relatives and condole with them or even pay a visit to the hospital where some of the injured are still recuperating. Stung by such harsh criticism, President Uhuru Kenyatta wrote personal letters to relatives and guardians of students who died following terror attack at Garissa University College. Some social media critics however note that the President needed to do more in his letter and take sole responsibility for the tragedy. President Kenyatta is indeed under undue pressure to act decisively against al-Shabaab more so in what the public perceives as his government’s failure to stem the growing violence by militants. Hundreds of miles of border with Somalia remain largely unpatrolled, and rampant corruption has allowed militants to slip across with ease. Claims are emerging of failure to act on prior warnings issued by the United Kingdom and Australian governments on the impending Garissa attack. In the Philippines, the role of the US has been acknowledged in Operation Exodus in the form of intelligence support.

In declaring a national day of mourning, both leaders in their respective contexts vowed enhanced security and closure on the matter. On his part, President Aquino pledged support to families of the fallen officers and a thorough independent investigation on the matter, while President Kenyatta declared that extremists would not succeed in creating an Islamic caliphate. The bottom line of these two cases is the question on the ability of countries in the Global South to adequately counter threats to their internal security amidst growing terrorism.

Despite support in the form of intelligence and technical support from allied nations in the Global North, led in large by the Americans and British, lack of coordination between the security organs (military and police), blunders in security operations, and a weak political bureaucracy are emerging challenges for countries in the Global South that are not impervious to various forms of militant insurgencies. Lessons need to be taken from both Mamasapano and Garissa, and add the Boko Haram menace in Nigeria, for authorities in countries of the Global South to amicably counter security threats posed in large by militant terrorists. Is the way forward then for enhanced regional counter terrorism cooperative strategies?

By Satwinder Rehal

Professor, Helena Z. Benitez School of International Relations and Diplomacy, Philippine Women’s University, Manila, The Philippines