Corruption in Uganda: Weighing the Options

|

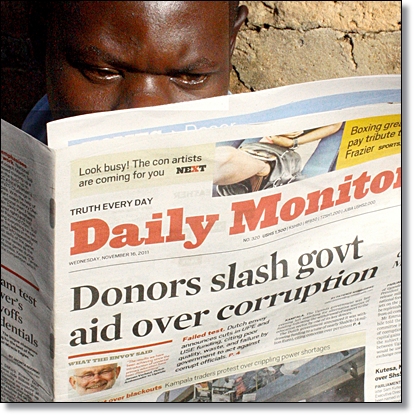

| Photo courtesy |

Voters should be concerned about graft. Politicians should either be touting their contributions to the fight against corruption or shaming their opponents about how they're contributing to the problem. In the U.S. this is political campaigning 101. After all, the electorate should be voting for an MP, or LC5 or a President, based on the amount of progress that's been made in their home region. A very common campaign catch phrase in the U.S. is "Are you better off than you were four years ago?"

Corruption plays a role in how the voting public in Uganda will answer that question. Was my primary school built with such shoddy materials and is now falling apart because someone skimmed money off the construction budget? Are my local clinics continually out of stock of medicine because lifesaving drugs are getting stolen along the supply route? Do I have to pay a policeman to investigate a robbery at my home? Are people in your constituency better off than they were five years ago? As representatives of the Ugandan government and the ruling party, you are the people on the ground who play a pivotal role in how your constituents answer this question.

How do you contribute to a more transparent and prosperous Uganda? What can you do every day to improve the performance of your government? Fortunately, there are volumes of research, a plethora of international agreements, protocols and conventions. In other words, there's no shortage of guidance on how to fix corruption.

Let me take a few minutes to talk about some of the approaches my government has used to curb corruption internationally. First, we have increased our own capacity -- through our Department of Justice and Securities and Exchange Commission -- to pursue cases of bribery of officials overseas. Since 2009, the U.S. has filed more than 100 enforcement actions and recovered more than two billion dollars in assets. We also use our authorities to deny visas to foreign corrupt officials to deny them safe haven in the U.S. The use of this authority in Uganda was announced last year and we will continue to use it as a tool in our efforts to make corruption less attractive.

We have provided billions of dollars in assistance to support anti-corruption and good governance internationally, as well as posted expert prosecutors and law enforcement officers to help countries build sound and fair justice systems. And we use economic assistance programs like the Millennium Challenge Corporation as an incentive to countries that have demonstrated political will in fighting corruption. Here in Uganda, USAID funds a really innovative project whereby civil society groups are training citizens to do audits of schools, health centers, and other services, and then recommending cases to the rewards and sanctions boards to ensure there are consequences for offenders.

I don't want to give the impression that the United States has a perfect scorecard on corruption. We've have our fair share of scandals that have caused a lot of pain and loss for those responsible as well as outraged millions of law-abiding Americans who are angered by their deceit. But our rather stubborn, enduring commitment to rule of law means that the guilty are eventually brought to justice. Corrupt politicians go to jail and their careers are ruined. Businessmen bribe government officials, we catch them, and they too have their careers and lives ruined by a prison sentence. While there are those today that still try to get away with it, I think for the most part we've made the risks of corruption outweigh the benefits. The RISKS OF CORRUPTION OUTWEIGH THE BENEFITS.

I'll come back to that thought shortly, but I'd like to pan out to the big picture for a minute -- and talk about how corruption impacts the U.S.-Uganda relationship. I mentioned earlier some of the actions we are taking to curb corruption internationally. One of the most powerful tools we have is the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which makes it illegal for companies and their employees to influence anyone -- anywhere in the world -- with any personal payments or rewards. Those found guilty may go to prison and companies are forced to pay exorbitant fines. U.S. law makes it highly unattractive to pay off foreign officials.

Now some of you may have heard of the African Leadership Summit that took place in Washington last August and which President Museveni attended. While lots of topics were covered, U.S. investment in Africa was an important theme running throughout the event. President Museveni returned to Uganda from that trip invigorated about the possibilities of increasing U.S. investment and trade in Uganda, eager about working with U.S. companies to create new industries in Uganda, and even more importantly -- new jobs.

Unfortunately, corruption is one of the biggest impediments to attracting more U.S. investment in Uganda. It is a cancer eating away at Uganda's investment climate. Corruption is routinely leading serious investors, who have their choice of investment destinations, to turn away from Uganda. And why wouldn't they? Corruption distorts economic activity, reduces competition, eats up profits, erodes trust, and sullies corporate images. Potential investors need only to look at the press to see daily reports of corruption in government ministries and throughout the society at every level. For instance, the Auditor General identified 1.7 trillion Ugandan shillings in unaccounted funds in fiscal year 2012-2013. That’s around 565 million U.S. dollars. Just as sadly, Uganda has slipped even further in Transparency International’s index on corruption -- the nation now ranks 140th out of 177 countries worldwide.

You might think that as district representatives none of this applies to you. However, I'm sure you would agree that an agro processing plant in your district -- for example -- could go a long way in curbing unemployment, taking vulnerable youth off the streets, and adding to the overall wealth of the community. Everyone benefits.

Too often, though, people see corruption as pervasive, endemic -- an impossible nut to crack. Many Ugandans feel helpless to change a society that has more or less condoned the "eating" that takes place every day. In the absence of vigilance on the issue, people have suggested that the U.S. and other donors should fix corruption here -- as if it could be part of one of our assistance programs. While we do have some programs aimed at improving transparency and governance, we can't do much without your leadership.

So where do you begin? I know Honorable Tumwebaze offered some specific guidance on how to curb corruption in your districts. I'd like to applaud him for highlighting that absenteeism is a form of corruption. We need people in the districts to be actively contributing to a better Uganda every day. Your government leaders have and will continue to help you learn your role in fighting corruption. Each of you has a different set of challenges. I am not here to be prescriptive on how you deal with this issue.

I promised I would come back to this idea of risks versus benefits. For me, this is a way of describing political will. As I said before, there is no shortage of guidance on how to fix corruption, but is there a shortage of the political will to actually do it? Lots of people talk about political will but it's not always clear what that really means or how it gets translated into our everyday work. In this case, political will is about deciding that the risks -- or downsides -- to corruption -- outweigh the benefits, and then enacting and applying laws equally to all Ugandans that bring corrupt people to justice. If corruption is going to be tackled, Uganda must realize that the consequences of a country and society permissive of corruption are too many -- and that the benefits of anti-corruption efforts, supported by strict adherence to rule of law, are far greater than the risks.

I will leave you with one last thought -- a real-world version of a centuries old philosophical idea. Perhaps it will help guide you as you return to your districts and contemplate your contribution to this effort. I would like you to consider asking yourself, "Is what I do today -- in my work, with my family, in my church -- is it helping Uganda? Does it move the country toward a brighter future? Or, it is disregarding my country and my fellow citizens in favor of a handful of individuals? Do my actions help my entire district or do they favor a handful of elites?" Collectively, you can decide that corruption is no longer acceptable. That it hurts your friends and neighbors. And it hurts Uganda. This kind of awareness will contribute to a healthier, secure, democratic, and prosperous Uganda. America is ready, willing, and able to partner with you to attain this shared vision. Thank you.

By Carla Benin

Deputy Counselor for Political and Economic Affairs, US Embassy, Kampala, Uganda.