Productivity in Africa: Stop Unwarranted Barriers!

An appropriate regulatory and institutional environment is a crucial component of a country’s economic growth strategy. If Africa is to turn more of its people into resources, it has to create an environment conducive to the development of entrepreneurs by decreasing barriers to doing businesses. The World Bank’s Doing Business surveys (covering 145 countries) have demonstrated that countries with higher regulatory costs have larger informal sectors, more unemployment and slower growth. This fact is increasingly recognised – but the question remains: how do we create the right regulatory environment for business growth in Africa?

Tourism – which has been described as South Africa’s ‘new gold’ – is recognized as an ‘immediate high priority sector’ under the government’s Accelerated and Shared Growth-South Africa (ASGISA) policy. Both government and the private sector are looking to the tourism industry to boost economic growth and employment. But the existing regulatory framework imposes exceptionally heavy constraints on the sector, largely as an unintended consequence of cumulative regulations.

In July and August 2006, SBP (an independent not-for-profit private sector development and research company that promotes strategic partnerships and a better policy, regulatory and operational environment for business growth in Africa, based in Johannesburg, South Africa) surveyed 278 formal sector firms in the tourism sector in Gauteng Province and the ‘Mpumalanga corridor.’ The survey sought to provide a picture of the efficiency cost (costs of regulation that arise because regulation changes the outcomes that markets would otherwise create) as well as the compliance costs (pure red tape costs incurred by businesses in time and consultants’ fees) for firms in the tourism industry in South Africa.

Gauteng, the province in which Johannesburg is situated, was chosen because it captured the most tourist ‘bed-nights’ in 2005, receives a large share of total tourist spending, and is the most visited province. In 2005 almost 50% of foreign visitors spent at least one night in Gauteng. Research shows that the management of the tourism industry and industry associations is largely concentrated in Johannesburg, and that national industry associations are also based in the province – providing a pool of individuals with a broad overview of the regulatory landscape and its implications for their businesses. The Mpumalanga corridor is an important tourism route between

SBP interviewed a wide range of firms in the tourism sector ranging from small businesses with an annual turnover of less than R250 000 (approximately $35 000 US Dollars) to large corporates with substantial market share in the tourism industry, reporting annual turnover above R100 million (approximately $140 000 US Dollars). Firms included single-person micro-enterprises, medium enterprises and large operations with over 75 employees. Interviews also covered a broad range of sub-sectors in the tourism sector on the assumption that they would face different sub-sector regulations and experience the costs of general regulations in different ways. The subs-sectors included:

- Accommodation, including hotels, bed and breakfast (suburban and township), backpacker establishments and hostels

- Food and beverage, including restaurants identified as deriving most of their income from tourism, and shebeens / pubs identified as deriving most of their income from tourism

- Tourism product providers, such as casinos, conference centres (excluding attached hotels), cultural villages, heritage centres and curio shops

- Tour operators, car hire companies, airport shuttle and chauffeurs, tourist bus owners and charter flight operators

- Intermediaries such as travel agents (a range of sizes)

Regarding factors which prevent firms from expanding their business, factors unrelated to regulations featured prominently. Just less than half the responses focused on low demand and unfavourable prevailing macro-economic conditions as reasons for limiting expansion. Clearly tourism is very much a consumer-driven sector, and relies on tourists’ willingness and capacity to spend money. A second major factor is the cost of crime and security, together with fears about crime, which accounted for just over 40 percent of responses. Fears about crime are of direct concern to tourism enterprises, since they are a potential deterrent for tourists, impacting negatively on demand.

Barriers to expansion related to labour concerns (non-regulatory), including skills shortages, impact of trade unions and poor employee productivity, accounted for a quarter of responses. High operating costs not related to regulations were also a significant constraint. Factors resulting from the state’s interface with business (regulation in a broad sense) accounted for one third of all responses. They include constraints imposed by the time, difficulty and cost involved in compliance with specific regulations, together with frustration at lack of government support and/or complaints of government incompetence, at national and municipal level. The latter factor is included both since interaction with government is a result of regulatory obligations, and because unsatisfactory interaction is likely to push up opportunity costs in respect of time required for compliance.

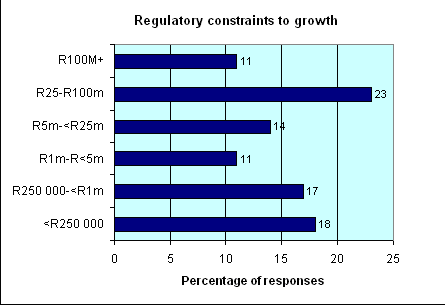

Perception of lack of government support and administrative incompetence, coupled with regulatory barriers to growth, is experienced most severely by firms in the smallest turnover band ( Looking only at responses specifically citing costs of compliance and regulatory barriers and red tape as constraints to growth, respondents in the R25m – R100m turnover band are most likely to report these as barriers to expansion. Firms in the two smallest turnover bands are second most likely to experience regulatory obstacles to expansion. The results are illustrated in the figure below. Figure 1: Regulatory constraints to growth Many of the difficulties reported by smaller firms are likely to be linked to capacity and human resource issues - small firms struggle to allocate the necessary staff time and skills to deal with compliance issues. For smaller and micro-businesses, simpler and clearer regulation and advice is clearly needed to assist these firms to comply with essential minimum requirements. This capacity is more available to the firms in the middle size bands, resulting in a dip in responses. However, once firms reach a certain size threshold, requirements become more complex and multi-faceted – a probable cause of the increase in regulatory constraints to growth reported in the R25-R100 million turnover band. In sub-sectors such as hotels and restaurants, even large firms often operate through small outlets – meaning that compliance with regulation within each outlet still has to be managed by one person. These outlets are nonetheless able to access some help and support from their head office in assimilating complex regulatory information. Regulatory constraints to growth are seen to drop off again in the largest turnover category – as firms are able to employ specialised staff or contract consultants to deal with their compliance requirements. By Sarah Meny-Gibert Researcher, SBP, Johannesburg