Fourth COVID Wave? Emerging Lessons for Kenya and Africa

A transformative trip of daunting discoveries

The captivating terrain across Africa, and not least Kenya, could be pregnant with meaning in the face of the resurgent global pandemic which is COVID-19. Like a beckoning vista of mountain ranges, every move closer to winning the war against COVID-19 reveals the massive scale masking the disguised distance setting apart the distant milestones. Shortly after countries such as India and Germany seemed to have managed their COVID-19 curves commendably, more vicious waves emerged. They have been sent back to the drawing board. As India battles her second wave with daily global records of new cases, Kenya’s third wave could be ebbing by late May, but perhaps only to test this well-known home of optimists and marathoners with a tactical retreat that may eventually give way to a more vicious fourth wave if the government, politicians, and the public quickly lower their guard in their characteristic response amid pandemic fatigue. The following yearlong marathon lessons from across the world can explain why.

Africa against the global standard

The rate of vaccination in Africa lags far behind the rest of the world, signalling the possibility of missing the target of vaccinating 60% of the population by the end of 2022. Supply chain constraints and vaccine hesitancy aggravate the already convoluted challenge.

As of April 26, the world had reported more than 148 million COVID-19 cases, 3.1% of them reported in Africa (more than 4.5 million cases). The global average case fatality rate was 2.1% against Africa’s 2.7%. The global recovery rate of 85% was below Africa’s 89%, though. Africa was contributing only 0.7% of the daily new cases globally, but almost three times that share (1.8%) of the daily new deaths globally. This was also reflected in 3.9% of the global COVID-19 deaths, 3.5% of the global severe cases (serious or critical), but 3.2% of the global recoveries. Again, the share of severe cases (serious or critical) out of the active cases in Africa, being 1.1%, was about twice the global average of 0.6%. The active cases in Africa made up 2% of the global sum of active cases, up from 1.4% on April 13, 2021.

The highest recorded COVID-19 recovery rates globally have been more than 90%, Israel posting the highest rate of 99% currently with an impressive combination of a very low case fatality rate of 0.8% as of April 26. Turkey displayed similar impressive scores with a high recovery rate of 88% and a case fatality rate of 0.8%.

The hidden key message is that African countries still need to be more cautious against the disease for the seemingly higher chances of developing more severe cases and deaths. The new highly contagious variants ravaging Brazil and India can only make matters worse for Africa, given the stressed and generally ill-equipped healthcare systems across the continent.

Kenya against Africa’s overall performance

As of April 26, Kenya had recorded 156,981 cases or 3.5% of Africa’s total cases. Kenya’s overall recovery rate had fallen from 80% months earlier to 68%, much lower than Rwanda’s 93% and Africa’s 89%. Kenya’s case fatality rate of 1.7% against Rwanda’s 1.3% and Africa’s 2.7% would easily match the shares of severe cases. The serious or critical cases in in Kenya as of this date made up 0.4% of her active cases, below the equivalent share for Africa (1.1%) and globally (0.6%). Though hosting 4% of Africa’s population, Kenya had 13.2% of Africa’s active cases and 5.3% of the serious or critical cases. Kenya had 6.2% of Africa’s serious or critical cases on April 21, 6.6% on April 19, and 6.8% on April 12. It is crucial to note that these shares went up from 5.1% as at March 31, 2021. Given the limited bed capacity and oxygen supply that many countries have experienced during a surge in cases, a rising share of serious or critical cases is a red signal. Strict measures of caution are necessary to avoid the stress India and Brazil have been experiencing.

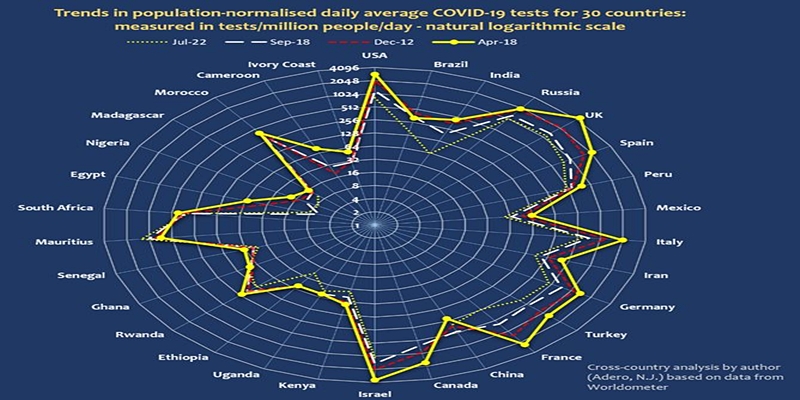

If the average rate of testing normalised by population is considered, the wide gap in reported numbers between Africa and the rest of the world becomes evident. The highest population-normalised COVID-19 testing rates have been more than 3,500 tests per million people per day, as already sustained in the UK and Israel. A similar rate calculated for Kenya as of April 26 was 74, much lower than Cameroon’s 112 (a recent significant improvement), Rwanda’s 239, and more than 400 for Brazil and India.

The fact that India and Brazil have stayed in the top-three global position of the ravaged league of leading COVID-19 country cases despite having lower population-normalised testing rates is telling: these two countries may in the long term turn the tables on the USA with high COVID-19 cases as they continue testing their large populations. This conclusion would apply to Kenya in the African scenario since it has a relatively high population and is already among the top-ten leading countries in Africa in terms of COVID-19 cases despite scoring low on the normalised testing index.

Model scenarios for Kenya and chances of a fourth wave

From the experience gained in this series by mathematically courting Kenya’s wavy COVID curves, several scenarios of possibility can be firmly stated. The wavy nature of the COVID-19 infections in Kenya has established a sinusoidal curve which reaches its peak every four months. This could be foretelling a fourth wave starting July 2021, hence a scenario for the resurgent trajectory.

Assuming high positivity rates and continued laxity among the citizenry, Kenya’s simulated upper trajectory is a red line of danger that can reach 400,000 COVID-19 cases on May 31, 2021. This is the pessimistic scenario.

Kenya’s simulated ebbing trajectory, herein referred to as the green line of hope, heralds the possibility of reducing cases after reaching a cumulative figure close to 167,000 cases on May 26, 2021. This model scenario assumes a declining trend in positivity rates sustained far below 10% and strict compliance with the prevailing containment measures.

Because health is a devolved function in Kenya, the 47 devolved units of governance have a key role to play in containing the pandemic. From a visual heat map, it can be seen that that the red signal of infections is evidently spreading out of Nairobi to the western part of Kenya.

Implications for containment decisions

1. As evident in Africa’s (and Kenya’s) less illustrious comparative metrics on case fatality rates, shares of severe cases, limited healthcare capacity, and inadequate vaccine supply, avoiding India’s experience calls for full compliance with COVID-19 containment measures as the first line of defence in the region. Not allowing pandemic fatigue nor normalcy bias to set in is the faster lane out of the bumpy road the ravaging pandemic has imposed on lives and livelihoods.

2.Expecting the pandemic’s wave to die off suddenly without sustained disciplined action would be a Panglossian view that can easily result in an uncontrollable surge in casualties. Governments must ensure timely responses informed by well-researched evidence as they prepare for the worst-case scenarios to cushion citizens against the adverse health and socioeconomic impacts of the pandemic.

3.For Kenya, sustained testing and tracing must accompany sound containment measures and coping strategies should a fourth wave pick up the pace in July 2021.

By Nashon Adero,

Lecturer at Taita Taveta University, Kenya.

nashon.adero@gmail.com