Kenneth Kaunda: The Humanist

Kenneth Kaunda was born at Lubwa in Chinsali District on 28th April, 1924, to a Church of Scotland missionary father David Kaunda from Malawi. Kaunda became Zambia’s first president on 24th October, 1964 till November 2nd, 1991.

Kaunda was a record breaker in several ways. He was one of the last two living first African presidents along Sir Dawda Jawara, Gambia’s first president. He was the first sitting president in Africa to concede defeat, quit office and vacate office right away after losing in elections. He didn’t attempt to rig or change the election results. Ironically, some African presidents are amending the constitutions of their countries to remain in power.

Although Kaunda was not as vocal as Nkrumah and Nyerere, he managed Zambia responsibly and diligently despite presiding over a one-party rule. Venter & Olivier (1993) note that “Kaunda became renowned as a passionate proponent of human rights in Africa and was sometimes depicted as conscience of Africa” (p. 25). His humanism philosophy that others call Kaundaism is in actual sense Ubuntu, the guiding principle in all societies in Central, East and South Africa region. Ubuntu is misconstrued to have originated from South Africa; See Mbigi & Maree 1995; Gade 2013) while it actually was practiced by all Bantu people.

Under his humanism philosophy, Kaunda coined the One Zambia, One Nation slogan which has since differentiated Zambians from non-Zambians. Under, and, after Kaunda’s watch, Zambia remained one nation. Power never got into Kaunda’s head. Vengeance never became his weapon of silencing dissenting voices.

Kaunda tried as much as he could to be as transparent and as humane as he could. He was not an angel or a know-it-all person. He knew that power was like a coat on somebody’s back. He knew that power rested in citizens hence when citizens voted against him, he conceded defeat.

Before going to elections, he told Zambians that he still had something to offer to Zambia. He told them that if they voted him out, he would not turn back. After Chiluba mismanaged the country and Zambians clamored for Kaunda, he did not seize this opportunity to make a comeback. He was a man of his own words. He never groomed his son or any protégé to take over after relinquishing power. This move helped Zambia to create a precedent and change leadership harmoniously.

Press (1991) quoting the Africa South of Sahara World Tables (1991) notes on the day Kaunda was defeated quoting him as saying “you win some, and you lose some elections.” Kaunda knew that elections were not the end in themselves. There is life out of the state house.

Three years after Kaunda exited power honorably, in the neighbouring Malawi, a long-time dictator, Hastings Kamuzu Banda found himself facing the same predicament. Banda was defeated in the elections; and unexpectedly though, conceded defeat. Arguably, after evidencing peaceful transition in Zambia. Coincidentally, Malawi is Kaunda’s ancestral land whose politics after Banda seems to be identical to Zambia’s. The same was replicated in Kenya in 2002 when a long-time dictator, former president Daniel arap Moi, agreed to step down; and let his party field another person other than himself. In the same elections, Moi’s protégé, Uhuru Kenyatta, was defeated by the opposition; and Moi had to concede the defeat of his person who was known as Moi’s project or project Uhuru.

Africa has witnessed many replications of conducting transparent, free and fair elections in some countries such as Nigeria in 2015 where the incumbent president Goodluck Ebele Jonathan was defeated by opposition candidate Muhamad Buhari. So, by underscoring such replications in various Africa countries, one can say that Kaunda did not only transform himself from a one-party dictator to the father of democracy of Zambia but also created a precedent in the whole continent.

Before the tumble of copper prices, Zambia’s chief export, Kaunda and his wife, the late Betty, used to bike and appear in public without any security details. At the time, Zambians used to enjoy copper money. Kaunda understood that the love that Zambians showed him had strings attached. The love revolved around positive economic performance. He knew that this love would quickly evaporate when things took a slump. And indeed, after the economy tanked, it evaporated. Kaunda told Zambians that they would not see him anymore in the streets freely biking with his wife as he used to do.

The plunge in copper prices should not be solely blamed on Kaunda. Press (Ibid.) notes that Kaunda sacrificed much by imposing economic sanctions against the secessionist white Rhodesian Government of Ian D. Smith at a great cost to the Zambian economy and its prime product, copper.

Like his great friend Nyerere, Kaunda contributed immensely to the liberation of Southern African countries that were still under the grip of colonialism in Angola, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe. There was nothing eminently dangerous for Zambia’s security like Kaunda’s decision to allow the Umkhoto we Sizwe (MK) or the spear of the nation, the African National Congress’ (ANC) military wing to establish its headquarters in Lusaka from where it carried out its attacks on South Africa. This action put Zambia in more danger than Tanzania which does not share a border with South Africa.

The editorial of Tumfweko Zambia News & Entertainment (2013) noted that “the ANC was headquartered in Roma while members of the military wing of ANC, MK, were based in Lilanda area.” Looking at the proximity, Kaunda’s decision was the result of a daring and fearless leader who was not afraid of taking risks.

The fall in copper price became a straw that broke the camel’s back. Zambia had much on its table than it could chew. Kaunda faced Zambians and told them to brace for tough times. If Kaunda did not tell them the truth, Zambians would not have prepared themselves to take up the challenge as they heroically did for the whole period their country supported the struggle in South Africa. Kaunda told the Zambians the bitter truth that he knew many people would hate him due to the predicaments they were facing; and the hard times that would follow thereafter. What straightforwardness!

As an honest, trustworthy and straightforward person, Kaunda left Zambians and the world at large wondering when he publicly said that one of his sons, Masuzgo Gwebe Kaunda, died of HIV/AIDS (Dec. 21st, 1986). Kaunda cited in Campbell (1987) notes that he did not how his son got AIDS. He would have treated this as a secret for fear of embarrassment. He had the power to coerce doctors to write a favourable report on the death of his son, but he did not. He wanted his people and the world to know that HIV/AIDS was not a respecter of persons or office. Thereafter, another prominent son of Africa, Nelson Mandela, did exactly the same by openly saying that his elder son, Makgatho Lewanika Mandela, died of HIV/AIDS. Mandela cited in Wines (2005) notes that his son died of AIDS.

Kaunda’s leadership skills kept Zambia united and harmonious for the whole time he was in power. Zambia is among a few African countries that have never been under military junta. All this tranquility, and of course, stability is credited to Kaunda’s charisma and skills as a manager of state affairs. The foundations he laid are firm.

Kaunda was not afraid of openly showing his true self, hobbies and aversions. Many Zambians remember his love for soccer and music that gave Zambia National Football Team a moniker of KK or Kenneth Kaunda. His song Tiende pamodzi ndi mtima umwe or Let’s Walk Together in One Spirit has never escaped the hearts and minds of Zambians.

Some quarters accuse Kaunda of being undemocratic. Easterly (2001) maintains that Kaunda discriminated against Bemba, one of the biggest tribes in Zambia for sympathising with the opposition, by favouring his Nyanja speaking tribe. Whether this is true or not depends on how one looks at Kaunda.

Arguably, despite such accusations, there is no recorded time at which Zambia tangibly suffered from any tribalism under Kaunda’s watch. I remember; sometimes, in Tanzania, his friend, Mwl Julius Nyerere was accused of favouring Roman Catholics simply because he was one of them. When research was conducted, it came to light that he was the only practising catholic in his government; and the second was his minister who had already acquired a second wife as opposed to Catholic diktat. To gauge the truth and just accusations, Sklar (1983) differs with Easterly (Ibid.) observing that:

In Zambia, the concept of participatory democracy was introduced as a national goal by President Kenneth D. Kaunda (1968, p. 20) in 1968. Subsequently, Kaunda (1971, p. 37) construed the concept to connote democratic participation in all spheres of life, so that “no single individual or group of individuals shall have a monopoly of political, economic, social or military power (p. 16).

Looking at Sklar compared to Easterly, one can notice a schism in analysing Kaunda. This is normal in social sciences given that claims must be substantiated. To avoid confusion and misleading allegations, there is a simple barometer that one can use to gauge whether a former leader. You just look at how they are treated by the successors after relinquishing power. When Chiluba humiliated Kaunda, many Zambians condemned it. Kaunda’s personal integrity and clean records enabled him to live comfortably after exiting power which is rare in Africa.

Few former presidents lived honourably and without any disturbance thanks to their integrity. These are Kaunda, Mandela, Nyerere and Leopold Sedar Senghor. However, there were other honest and diligent leaders who were maltreated by their successors despite having committed no crimes whatever. Such are former and first president of Cameroon Ahmadou Ahidjo who died in exile in Senegal and his remains have never been returned home to be reburied honorably by the person he ceded power to, Paul Biya, Cameroonian long-time dictator. Another victim of political uprightness was Somali’s first president, Aden Abdullah Osman Daar, after being defeated in election by his former Prime Minister; Abdirashid Ali Shermarke in 1967. Daar lived a normal life up until he was imprisoned in 1990 for expressing his views against the former tyrant Mohamed Siad Barre. Daar was released after the fall of Barre a year after and lived a normal life until he died in Somalia at the age of 99 years old. Those were the lucky ones. Most of the founders of African countries were toppled and other killed.

Kaunda’s legacy

Kenneth Kaunda (KK) will be remembered as the manager of public affairs who did not rob his country. No corruption allegations were put on him. Kaunda united Zambia under his slogan of One Zambia, One Nation which made the country peaceable despite being surrounded by countries that were still under colonialism. Like Nyerere, Kaunda turned Zambia into a hub for freedom fighters in Southern African region by providing headquarters to many liberation movements.

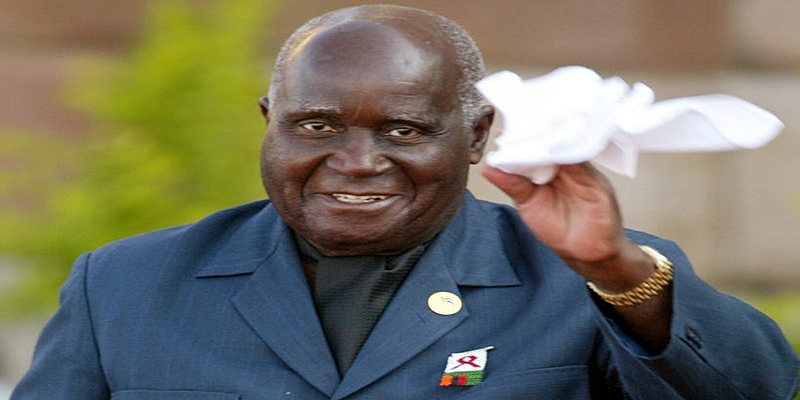

Kaunda’s leadership was guided by the philosophy of collectively running of the business of the state. His famous song Tiende Pamodzi or Let us Walk Together speaks volume not to mention his love of football which resulted to calling Zambia’s national football team KK the initials of his name. Also, Kaunda left another indelible mark on fashion. His Kaunda suit will always be called so and worn by many in Africa not to forget his white handkerchief that has always been in his hands as a symbol of peace for the man and his mission not to forget the nation. One Zambian once said that Kaunda was more than a president. He was a marque, especially if we consider what came to be Kaunda Suit, a simple suit unique and that started to surface after Kaunda invented it. Indeed, even this is his legacy for future generations.

Kaunda will also be remembered as the leader who wanted to see Africa united. His vision for Zambia was huge, mainly thwarting tribalism without using force. He will always be a point of reference vis-à-vis conceding defeat as he did in 1991 when he lost in the general elections that saw his exit from power. So, too, Kaunda will be remembered and honoured for not interfering in the government of his successor something he would have done if he wanted.

Just like anybody else, Kaunda was no angel. One of the weaknesses is that he left power unwillingly, as noted above, after being defeated in the general election in 1991. Furthermore, Kaunda will be remembered for his inability to conceal his emotions. When anything that would trigger his tears happened, contrary to African beliefs that a man should not cry, Kaunda would not subdue or conceal his emotion even where he is supposedly expected to “tough it out” as an African man who should not show his weakness like a woman. Such a trait depends on how you look at it. Sometimes, it can be seen as a sign of sincerity and openness or weakness.

Abridged from Chapter Five of the Book Africa's Best and Worst Presidents: How Neocolonialism and Imperialism Maintained Venal Rules in Africa- Langaa RPCIG, Bamenda Cameroon, 2016 By Nkwazi Mhango.

Mhango is a lifetime member of the Writers' Alliance of Newfoundland and Labrador (WANL) and author of over 20 books among which are Africa Reunite or Perish, 'Is It Global War on Terrorism' or Global War over Terra Africana? How Africa Developed Europe and has contributed many chapters in scholarly works.