Aiding and Protecting Civilians in South Sudan

Introduction

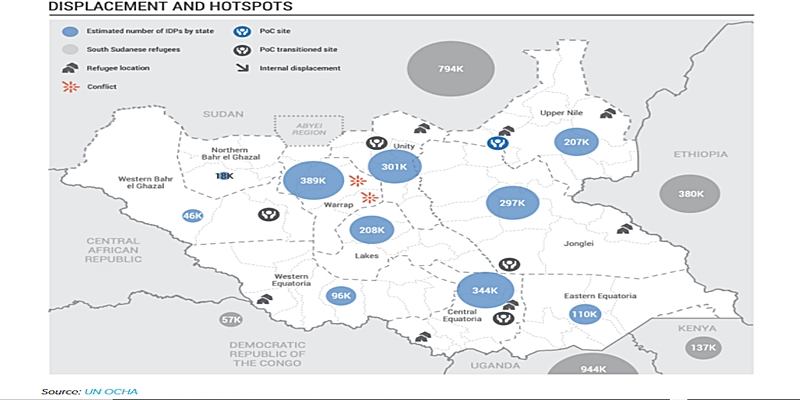

With 4 million people—one third of its population—unable to return to their homes, South Sudan continues to face one of the largest displacement and humanitarian crises on earth. Terrible floods, cycles of violence, and the slow implementation of peace have made matters worse. Yet the attention of donors and diplomats is waning.

In 2022, the poor and landlocked East African nation will continue to face immense—and probably increasing—political tensions and humanitarian needs. As the top United Nations official in South Sudan recently warned, the 2018 peace agreement, which brought an end to nationwide fighting, could be undermined by stalled implementation. This would risk a return to the kind of large-scale violence that caused an estimated 400,000 deaths from 2013 until peace was declared. By March 2022, the UN Security Council must renew its peacekeeping mission in South Sudan, known as UNMISS. This will give officials who care about South Sudan—notably, in neighboring countries and the UN Security Council—an opportunity to highlight these challenges and to step up efforts to keep peace on track. They should seize this opportunity.

The United States is the largest humanitarian donor to South Sudan and has a pivotal political role. Yet Washington is hamstrung in its response because of a lack of high-level political representation and engagement. There has been no U.S. ambassador since mid-2020, and a special envoy position has been vacant since August 2021.

In the meantime, the humanitarian crisis shows every sign of getting worse. The 2 million internally displaced people (IDPs) remain vulnerable to hunger and renewed violence, and some face yet another risk. Tens of thousands of IDPs lived until recently under UNMISS’s direct protection in what are known as Protection of Civilian sites (PoCs). However, UNMISS has handed over control of all but one of these sites to South Sudanese authorities and redesignated them as IDP camps. Most of the IDPs living in these redesignated camps belong to the country’s ethnic minorities and are living in areas dominated by forces that had previously fought against them. A lack of progress on security sector reforms outlined in the 2018 peace agreement has led to a precarious situation. Many of the people now policing the sites are the same as those who committed the violence that forced people to seek refuge in the UN bases in the first place.

This spells danger. In the year ahead, even as UNMISS focuses on supporting broader peace implementation, it must maintain attention on protecting civilians. While UNMISS seeks to deter violence and protect a broader swath of civilians by moving toward farther-ranging patrols and temporary operating bases in potential hotspots, it must do more. It should maintain a preventive presence and rapid response capability on or near the former PoCs, which themselves will remain hotspots for renewed violence. The mission should also refrain from transitioning the final PoC in Malakal until there are sufficient local security arrangements, clear transition plans developed with IDPs and humanitarians, and guarantees of a sustained UNMISS presence.

As the Security Council prepares to renew the UNMISS mandate, the breadth of mission tasks merit additional resources. However, given competing global emergencies, this remains unlikely. Short of new resources for the mission, an effective strategy to protect civilians will require the Security Council members and donors to step up diplomatic engagement and humanitarian assistance. UNMISS, for its part, will need to carefully balance use of its existing resources by carrying out regularly updated risk assessments of the redesignated PoCs.

As South Sudan enters its second decade as a nation, its people—especially, its internally displaced people—still face immense challenges. This is not the time to forget them.

Still a Displaced Nation

South Sudan gained independence in 2011, following a long civil war and an overwhelming vote to split from Sudan. But it has experienced war for most of its short history as an independent nation. A power struggle between the leaders of South Sudan’s two largest ethnic groups, President Salva Kiir, an ethnic Dinka, and Vice President Riek Machar, an ethnic Nuer, sparked tensions that led to intense fighting starting in late 2013. Violence by both sides, replete with ethnically targeted atrocities, led to an estimated 380,000 deaths and displaced millions.

A short-lived peace agreement in 2016, followed by a Revitalized Peace Agreement in 2018, finally ended most fighting at the national level. The agreement outlined power-sharing arrangements through a transitional unified government led by Kiir and Machar, which is to establish a new constitution, unified armed forces, and accountability mechanisms ahead of elections. But subnational violence—fighting at a local level but often between forces with ties to elites at the national level—has persisted. Few of those displaced, whether as IDPs or as refugees in other countries, have been able to return to their homes.

In 2018, Refugees International described South Sudan as a “Displaced Nation,” after a third of its pre-war population had been forced to flee their homes. Today, following some returns home, but also newer displacements or re-displacements of those who had returned to their homes, that number hasn’t budged. With 2.3 million South Sudanese living as refugees in surrounding countries, mostly in Sudan and Uganda, and another two million displaced within the country’s borders, South Sudan remains among the world’s unfortunate leaders in both categories.

For four reasons in particular, conditions have grown even more daunting of late.

Historic Flooding

Flooding in recent months, the worst since the 1960s, has affected at least 800,000 people and driven more than 200,000 from their homes—mostly in the northeastern states of Jonglei, Unity, and Upper Nile. The floods caused by heavy rains have destroyed homes, schools, markets, and health facilities, and slowed the delivery of humanitarian aid and damaged crops ahead of the next harvest season. They have also raised the risk of waterborne diseases and contributed to an outbreak of hepatitis E in the burgeoning IDP camp in Bentiu, which now hosts more than 120,000 IDPs. Assisted by UN agencies and humanitarian organizations, South Sudan has built several miles of dikes, yet the water levels in many places show little signs of receding.

The country needs more help in providing food and shelter to people who have lost their homes. In the longer run, the South Sudanese government needs more money from development funders like USAID and the World Bank to reduce these disasters. This hinges, however, on relative physical security and good governance in a country that is rife with corruption.

Subnational Violence

The 2018 peace agreement has deterred the signatories to the earlier pact from fighting one another countrywide. But fighting in various regions of the country has persisted, often tied to clashes among the ethnic-torn nation’s political elite. This violence took 2,000 lives in 2020 alone.

The number of civilian casualties fell by nearly half in 2021, UNMISS has reported, largely due to a reduction in tensions in Jonglei state and also to a peacekeeping approach that emphasizes mobility—the use of temporary bases and mobile patrols. But this still means more than 1,000 deaths in 2021 and this violence has not gone away. In Tambura county, in the southwestern part of the country, politicians exploiting ethnic tensions stoked violence last June that led to dozens of deaths and displaced 80,000 people, few of whom have returned. The fighting involved local groups as well as fighters affiliated with government and opposition forces. UNMISS set up a temporary operating base and helped facilitate delivery of aid, but the scale of the violence was beyond what UNMISS had the resources to prevent. As a forthcoming analysis by the Effectiveness of Peace Operations Network (EPON) will highlight, the fact that few of those displaced have returned also shows the limits of trust in the mission’s likelihood of staying and ability to deter future violence. The threat of further violence across the country persists, as politicians jockey for position before the national elections scheduled for 2023.

An Uncertain Peace

Besides the flooding and political violence, the slow implementation of the revitalized peace agreement remains a major obstacle for those displaced who want to go home. Refugees International has highlighted their lack of confidence in the chances for peace.

Progress has been made. In late 2018, South Sudan’s neighbors facilitated the return of opposition leader Riek Machar two years after he had fled the capital and then the country. The central government has appointed governors and established a transitional parliament, in line with the 2018 agreement.

But obstacles loom. The transitional parliament remains essentially non-operational, having yet to form key committees or pass legislation critical to drafting a constitution. A group of military leaders within Machar’s party tried to depose him last August, failing but forming their own faction and undermining his power. Last September’s military coup in neighboring Sudan derailed talks between this new faction and President Kiir’s party, which the Khartoum government has hosted. Sudan and Ethiopia, both of which play a key role within the regional group acting as guarantor of the 2018 peace agreement, have respectively faced a coup and bloody ethnic conflict. With diminishing outside attention and ongoing internal tensions, the writing of a new constitution and the implementation of transitional security arrangements have stalled. Agreements between Kiir and Machar to form a unified armed force have been delayed by disagreements over command ratios and by a lack of funding for training centers. And progress is stymied on creating a court, run jointly by South Sudan and the African Union, to hold the perpetrators of past atrocities to account.

Rising Food Insecurity

Because of the flooding—and the occasional drought—as well as the violence and Covid-related restrictions on delivering humanitarian aid, South Sudan has seen its highest levels of food insecurity since its independence. About three-fifths of South Sudanese still in the country, an estimated 7.2 million people, faced severe hunger in 2021; more than 100,000 faced famine levels. Children under five are suffering through the worst malnutrition since 2013; some 1.4 million needed treatment for acute malnourishment in 2021.

Prospects for 2022 are not encouraging. Flooding has disrupted the planting of crops, and political violence has hampered delivery of humanitarian assistance, in part through the targeting of aid workers. The UN reports that more than 911 metric tons of food and nutritional supplements were looted or destroyed in 2021. A senior UN official briefed the Security Council in December 2021 that the humanitarian situation deteriorated late in the year, as the needs are “outstripping our ability to adequately respond.”

Waning International Attention

As South Sudan’s troubles have mounted, the contributions by international donors have not kept up, and what little diplomatic attention the country received has been further overshadowed by newer crises in Afghanistan and Ethiopia.

Despite the rising food insecurity, the amount of humanitarian funds from international sources has been stuck at around $1.4 billion for each year for the past seven years. Barely two-thirds of the $1.7 billion in humanitarian assistance that the 2021 South Sudan Humanitarian Response Plan called for had been received by December, though international donors provided an extra $13 million of emergency funding to deal with the flooding.

This shortage of funds has led to dramatic decisions. Last April, the UN’s World Food Program cut rations in half for some 700,000 refugees and IDPs, and it announced in September that it would suspend aid for more than 100,000 displaced people in parts of South Sudan. The United Kingdom, a leading donor, reportedly cut its humanitarian funding for South Sudan by 59 percent.

The United States government still donates the most money to South Sudan, more than $800 million in 2021. But diplomatic and political attention has faltered. The Biden administration’s special envoy for the Horn of Africa has focused on the political crises in Ethiopia and Sudan. The previously established Office of the U.S. Special Envoy to Sudan and South Sudan has not had a special envoy since August, and the ambassadorship to South Sudan remains vacant. This has meant a “massive gap” in U.S. representation in South Sudan, as a humanitarian worker told Refugees International. These positions need to be filled, and the Biden administration should reinvigorate efforts at the UN Security Council (as part of the influential troika with Norway and the UK) and with regional governments to put the peace agreement into effect. The administration should also urge other countries to step up their aid.

The UN’s Protection of Civilian Sites

One of the most vulnerable populations in South Sudan are the IDPs who, until recently, were living in UNMISS-controlled camps, known as Protection of Civilian sites, or PoCs. They were established originally to provide emergency protection to civilians fleeing often ethnically-targeted violence, a threat that persists and could be unleashed again on a large scale. Even as UNMISS sheds direct responsibility for these camps, it must sustain efforts to protect them.

Origins of the PoCs

These sites came into being in late 2013, when tens of thousands of civilians fleeing violence sought refuge in UNMISS bases. The peacekeeping mission’s decision to let them in likely saved their lives. These IDPs belonged mostly to ethnic minorities, in areas dominated by rival, more powerful ethnic groups. The sites were meant to protect people for only a few days, but persistent threats and the ethnic dimensions led to the need for prolonged protection. Many of these IDPs saw their homes destroyed or seized by people from other ethnic groups, and the camps became relatively reliable and efficient centers to distribute humanitarian aid.

As many as 200,000 South Sudanese have lived in the UN camps for the past several years. But once the peace agreement was signed in 2018 and the nationwide fighting ended, plans to shift control to South Sudanese authorities began to be implemented. Since September 2020, all but one of the five PoCs have changed hands. Plans to redesignate the last one, the Malakal site, are underway, but UNMISS says this will not happen until political and security dynamics allow.

Rationales for Transition

Various actors have given several reasons for transitioning oversight of the PoC sites from UNMISS to South Sudanese authorities. UNMISS has argued that more than half of the mission’s budget has been spent on protecting just a tenth of the country’s displaced people. Giving up responsibility for the sites frees up capacity to deter violence elsewhere through temporary operating bases and farther-reaching peacekeeping patrols. UN Mission personnel have contended that the relative stability that the revitalized peace agreement ushered in—at least with respect to nationwide violence—ended the immediate threat to IDPs, which suggested they were staying in the sites more for the humanitarian aid than for protection from violence. President Kiir, among others, wanted to transition authority for the sites to show confidence in the peace process and to encourage displaced people to return—and to make sure the sites didn’t become havens for opposition fighters.

Humanitarian groups providing aid to the IDPs mostly agreed with the desire to close or turn over control of the sites once they were safe. As Refugees International reported in 2018, the sites faced surges in crimes and a rising culture of dependency. But there is disagreement over what constitutes being safe. Even before the camps changed hands, Refugees International, among others, and IDPs themselves worried about ethnic-based violence. While access to services was a factor in people’s decisions to stay, safety concerns were consistently and often predominantly cited as reasons for people remaining in the sites. A civil society leader in South Sudan explained to Refugees International that many of the same officials who had led or joined in the ethnic-targeted violence that had caused people to flee their homes in the first place would now be in charge of protecting those people.

Starting in September 2020, UNMISS assessed the risks for each of its camps and shifted control of sites in Bor and Wau then, later, in Juba and Bentiu. Humanitarian groups reported problems with a lack of transparency with camp residents and aid workers alike on timing and planning for continuation of humanitarian services. Communications have reportedly improved, but many humanitarian actors still echo concerns identified in an independent review of UNMISS in December 2020. The independent review underscored the need for improved two-way consultations that take humanitarian and IDP perspectives more seriously as decisions are made about the sites and safety of IDPs.

Nicholas Haysom, the head of UNMISS, reported to the Secretary General that the mission’s move toward a more mobile posture has helped to deter violence against civilians. However, its risk assessments have been criticized for focusing too narrowly on an absence of fighting between the main signatories to the peace agreement, and for largely ignoring the persistent regional violence and the risks of renewed violence in the camps.

Centers of Vulnerability

While the worst fears in transitioning the sites haven’t materialized, these sites are still vulnerable. Humanitarian workers on the ground tell Refugees International about high rates of crime and gender-based violence. Floods in and around the Bentiu site contributed to a hepatitis E outbreak and pushed the number of local IDPs past 120,000. In recent interviews with the Center for Civilians in Conflict, Bentiu IDPs accused the local joint police force, made up of government and opposition police officers, of extortion and physical abuse. A forthcoming report by the Effectiveness of Peace Operations Network concludes that unless things change, the South Sudanese military and police will continue to pose one of the greatest threats to the nation’s civilians, particularly in the former UN-run sites.

Even if the mandate renewal comes without additional resources, UNMISS cannot afford to turn its attention away from its legacy role in the PoCs and must provide adequate levels of protection. As the peacekeeping mission moves on from its role as the primary security provider for these sites, it must continue to protect the IDPs by training and monitoring the camps’ protectors and by responding quickly if violence erupts. It must also be willing to reprise its role in providing areas of last refuge to those targeted for violence who seek safety near UNMISS bases. If no one else will help, the UN peacekeeping mission must do so.

UNMISS will also likely face pressures by the government to facilitate returns of refugees and IDPs across the country even as many areas of return remain unsafe or highly food insecure. As Refugees International has highlighted in past reports, various actors within South Sudan have sought to manipulate such returns for their own purposes, whether to gain humanitarian aid or to repopulate areas on ethnic lines. A pending census and elections planned for 2023 will only increase political tensions and increase incentives for such manipulation. UNMISS, alongside the UN refugee agency and other humanitarian actors, must remain vigilant and carry out appropriate conflict sensitivity and risk assessments as part of its due diligence in any returns with which they are involved. They must also push back whenever political actors seek to manipulate such movements.

The Last UN PoC Site

The sole remaining UN-controlled site is in the northern town of Malakal, near the border with Sudan, and is home to 34,000 IDPs. It hasn’t been turned over to South Sudanese authorities yet because of the Upper Nile region’s political tensions and the fact that the majority of PoC residents are Shilluk, while Malakal remains occupied by a Dinka-dominated security force. The Shilluk, the third largest ethnic group in South Sudan, have long clashed with the Dinka-dominated armed forces for political power and claims to ancestral lands. One wild card is a powerful Shilluk general, Johnson Olony, who is part of the faction that broke from Machar and has often changed allegiances in pursuit of Shilluk interests.

As Refugees International highlighted following a visit in 2019, IDPs cited fears for their personal safety as the reason to remain inside the Malakal PoC, along with the fact that they had lost their homes and property and had nowhere to return.

Recognizing these unique challenges, along with obstacles the other sites have faced, UNMISS has stated that the Malakal camp won’t be turned over to the South Sudanese until “political and security conditions allow.” But planning for a transition is well underway and UNMISS assessments on what constitutes a secure environment have often been at odds with assessments of safety by humanitarian actors. Humanitarian workers involved in discussions of the camp’s future have told Refugees International they fear the UN will hand off control within a matter of months.

This should not happen until there has been real progress in creating a unified police force, made up of government and opposition officers, as well as enough UN peacekeepers to keep watch and to step in quickly if necessary. UNMISS should also work with South Sudanese authorities to settle issues involving housing, land, and property as many of those displaced have found their homes now occupied by others. The peacekeeping mission must keep updating its risk assessments and contingency planning and, in any event, act gradually and in full consultation with humanitarians providing aid and the IDPs themselves.

Conclusion

As Security Council members prepare to renew the UNMISS mandate in March 2022, they should reinforce the mission with increased resources and stepped-up diplomatic engagement. The year ahead will come with risks of further political violence, which UNMISS should strive to prevent, especially as the 2023 elections approach. The UNMISS mandate must remain focused on the implementation of South Sudan’s peace agreement. But the mandate must also continue to prioritize the protection of civilians and pay special attention to past and present PoCs. These sites remain vulnerable places, prone to violence that could spread.

At the same time, if South Sudan’s IDPs are to be kept safe and see their needs met, the momentum for peace must be revived. Only then can the displaced South Sudanese return home with dignity and without fear. For this to happen, the eyes of the international community must remain on South Sudan. The largest donors must back their humanitarian commitment with diplomatic efforts to keep the peace agreement on track. The world must not forget one of its most vulnerable countries, nor fail to protect the most vulnerable within.

Recommendations:

UN Security Council members should:

- Renew the UNMISS mandate with a sustained focus on protection of civilians and a specific call for regular risk assessments and contingency planning for rapid reaction to violence in its former PoCs and in potential areas for return of IDPs and refugees.

- Increase resources and political support for UNMISS to carry out both main aspects of its mandate—supporting the peace process and protecting civilians—including the peacekeepers and equipment needed to expand the use of temporary operating bases in dangerous places while continuing to protect IDPs in the former UN-run camps.

UNMISS should:

- Maintain a preventive and rapid reaction presence in or near former PoCs and utilize regularly updated risk assessments and contingency plans for the former PoCs to inform and balance the use of mobile patrols and deployment of peacekeepers and equipment to temporary operating bases.

- Refrain from turning over the Malakal PoC to South Sudanese control until certain conditions are met, including:

- Establishment of a joint police force made up of government and opposition police officers;

- Efforts to address housing, land, and property issues;

- Transparent planning that includes inputs from humanitarians and IDPs;

- Guarantees of a sustained UNMISS presence in the area and contingency planning;

- A comprehensive security assessment, as required in the current mandate, that determines that civilians will not be subjected to human rights abuses.

- Remain prepared to protect civilians who gather near its bases.

- Ensure the safety and legitimacy of any return of IDPs and refugees to their areas of origin by working with the UN refugee agency and other humanitarian advocates to carry out risk assessments of potential areas of return and to monitor potential manipulation of returns motivated by ethnic or political purposes.

Donor countries should:

- Fully fund the Humanitarian Response Plan for South Sudan in 2022, which reflects the high levels of food insecurity and the need for emergency funding to address the effects of flooding.

- Provide funding for quick impact and longer-term development efforts, including disaster reduction projects to mitigate flooding, while paying attention to the possibility of corruption and misuse.

The U.S. government should:

- Appoint a U.S. ambassador to South Sudan and a special envoy for South Sudan or another high-level official within the office of the Special Envoy for the Horn of Africa to lead diplomatic efforts toward a peaceful transition and sustained multilateral humanitarian efforts in South Sudan.

- Maintain robust humanitarian funding for South Sudan and increase diplomatic efforts to urge other donor countries to give more.

- Support UNMISS’s ability to carry out both main aspects of its mandate—supporting the peace process and protecting civilians—with political backing and enough resources to expand its mobile protection stance, while maintaining the ability to protect IDPs in former UN-controlled camps.