Making Democracy Work In and For Africa

I made time to look at some literature on the theory of democracy during which I stumbled upon this very interesting definition: ‘a system of government in which the people of a country can vote to elect their representatives.’

Then I said to myself, this is part of the problem. And this is a definition that is attributed to the Oxford University. They are not alone; may people, including some political leaders, think that democracy is all about electing leaders into political office. Yes, regular periodic elections are a critical feature of democracy. This should also mean that the power is in the hands of the electorate and that governments should be at the service of those who elect them. Clearly, in addition to elections, ‘democratic states are those governed by the rule of law with access to decision making for all social groups.’ In other words, apart from electing their leaders, all citizens must be treated equally; they must be included – able to participate in the major decisions of the state; they must have the freedoms to do so by associating; by expressing themselves and even by protesting freely within the law. But critically, their welfare must be guaranteed through the provision of basic services – that is the democratic dividend.

All of this should be to the knowledge and understanding of those for whom it is being done. The people should be aware and should be part of actions and decisions being taken on their behalf. It is said that what is for me, without me is against me. Therefore, a government can only claim to be democratic when it “is effective and efficient in carrying out its duties, its work is transparent and accountable, and everyone is aware and can access its services.

Now what is the prevailing situation in Africa? In one of its studies of 30 countries Afrobarometer said that majority of Africans prefer democracy as a political system over and above autocratic ones. That is a massive aspiration but the reality, according to Freedom House, is that out of 54 countries in Africa, only 12 could be considered as ‘free’ over the last 15 years while only 7% of the continent’s population live in such societies.

And, all economic indicators including the hunger and happiness indexes show that the worst performing countries are in Africa. On top of this grim reality, democracy is being overthrown not necessarily through the barrel of the gun rather; through the ballot box, aided and abated by the very institutions which ought to protect it.

State security apparatus are increasingly being used to harass, intimidate, and detain opposition leaders and their supporters; persecute predecessors and officials of the past governments. We are also witnessing Parliaments working in cohort with the executive in some countries, to manipulate the constitution and pass laws that are designed to entrench the powers of the executive. At the same time, in many countries, the judiciary, which is supposed to hold the balance between the opposition, the public and the government, works to the advantage of the ruling party, and those with critical views. The professed fight against corruption is only as potent against the opposition as it is protective of the status quo; and elections management bodies whose responsibility it is to impartially and fairly conduct free, credible and widely acceptable elections, are instead doing the bidding of the ruling parties. These developments created space for the several military take overs which, as we have seen recently, receive public acclamation.

Are the challenges to effective democracy limited to internal factors? While I think the answer is no, this is a question I will leave to the discussants to deal with. But from my practical experience having served as an opposition leader, as president, past president whose party is in opposition and who has led eight elections observer missions; I know that democracy can work in Africa and for Africans depending on the leadership. How?

Ensure that the energy and resources invested in elections monitoring/observation are invested in double folds in monitoring of governance and the processes leading up to elections. Do not wait after the horse has bolted before you close the stable. Early warning can only be effective when they are backed with early action. When democracy go beyond regular elections and embrace good governance, the safeguard of human rights and the rule of law; it provides hope to the citizens through tangible deliverables particularly on the economy, access to social services and the protection of human rights. Where constitutions and international best practices are routinely violated there must be swift, strong, consistent, sustained and deterring response from local and international civil society and from the regional, continental and international bodies whose protocols run contrary to such violations. The autocratic leaders and families should be targeted with decisive and effective legal, travel and economic sanctions.

Local and international civil society organisations must synergise, scale up and deepen their interventions. And here is the reason: democracy without a vibrant, independent and public–centered civil society is like a person with a weak immune system. They play the critical role of ensuring that the system remains healthy and functional. They hold the balance between the government and the citizenry and they should do so by drawing the attention of the government to lapses; issues of corruption and other governance inefficiencies. A listening government should respond by taking remedial actions but if they don’t, the CSOs should be strong enough to call out the authorities fairly and in a professional way. This require synergies between local and international CSOs which ensure that their positions and messages like your annual barometer are innovatively communicated to communities in their local languages. This will increase public awareness about government actions and or inactions. This way, the overbearing considerations of ethnicity and regionalism would be minimized in making electoral choices.

Now let me talk a little bit about the importance of electing good leaders. Democrats and autocrats emerge from the character of the leader. You cannot give what you do not have. If you are not a fair -minded person, you would not be a leader who can govern fairly. If, as an individual, you do not have enough knowledge and experience, you cannot be an effective and efficient leader. If you are not caring as an individual, do not feel sorry for others; you will not be a leader who would be bothered about protecting citizen’s rights or delivering for their welfare. Democratic good governance is a matter of knowledgeable leadership with a vision, compassion, and a commitment to positively impact the lives of the citizenry. And if you are in it to serve, you must be strong enough to stay focused. Therefore, there is a great need to scrutinize presidential candidates and support the election of leaders based on good character and proven record of leadership and knowledge.

Please allow to, with humility, share my personal story with you, to help put into context how democracy works in and for Africans. I was elected president of the Republic of Sierra Leone in 2007; after I had built a thriving insurance company. My election was few years after my predecessor had ended our country’s very brutal 11-year civil war. Throughout those depressing war years, I was in the country even though I had the means to leave. So I witnessed firsthand the horrors, the pains, and the devastation brought about by the war. Roads, water, and electricity infrastructure were completely destroyed. Schools, hospitals, and government institutions were similarly comprehensively wrecked. Businesses collapsed or closed down and evacuated. Everything then became a priority including the building of the fragile peace that existed. In fact, there was justifiable fear that the country could easily relapse into violence.

I was, therefore, very clear in setting the right tone for the building and consolidation of peace and democracy, knowing that my government did not have the luxury of time, financial or the human resources to resolve all the problems in five or even ten years.

Detoxify the politics and foster inclusiveness. My first step was to send the right message for a smooth transition. Immediately after I had been officially notified that I had won the election, while my party and supporters were enjoying the euphoria, I drove to the outgoing president to thank him for his service, for presiding over the elections, and to inform him that I would be calling for his wise counsel periodically. I then moved to the outgoing vice president, who lost the elections to me, and found that the Inspector –General of Police had already withdrawn his security detail. I telephoned him right away and instructed that the full complement of the vice president’s security be restored immediately. I then assured him of his safety and that he could stay at the official residence until such a time he was ready to move to his private residence.

The next step was the broadcast of a public announcement for all cabinet ministers and other senior government functionaries of the outgoing administration to stay in their positions until the new appointees were sworn in, report for duty and a comprehensive and peaceful handing over was completed. Those actions were so reassuring that even some of the former ministers and heads of agencies who were already at border crossing points trying to flee the country, voluntarily returned and reported in their offices. I held my first cabinet with ministers of the past administration.

My first trip out of the country was to the chairman of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), and other leaders in West Africa. In my delegation were the leaders of the opposition both in and out of parliament.

Get the Public Buy In To Make the Public Service Work

I knew that we could only make substantial progress if we had our priorities right and ensured that we bring the people along in our governance journey. We, therefore, developed what we called the ‘Agenda for Change’, by which we set ourselves five key priorities with clear deliverables and timelines, drawing from my over 30 years private sector experience. These ideas could not have been implemented within the same governance framework. We had to adopt the Open Government Initiative (OGI), whereby government officials, including myself and my cabinet ministers, would interact in person with the public in town hall meetings. Through this initiative, citizens were consulted on public policy formulation, programmes, projects and their feedbacks sought on the implementation process. We also had radio and television phone-in programmes curated by the OGI/OGP secretariat which allowed regular public scrutiny of my government and feedback on what we were doing.

I also subjected my government to the African Peer Review Mechanism. This openness helped us to confirm our weaknesses, our strengths and thus helped to shape our service delivery interventions.

Do Not Target Opponents, On the fight against corruption for instance, we ensured that the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) Act was reviewed and given prosecutorial powers which greatly enhanced its autonomy. Past government functionaries were not targeted and indeed, sitting government ministers who were accused of corruption had to step aside until their investigation was completed.

These actions paid off in many ways. First, we had a very smooth transition which had a positive impact on governance and peace. We restored hope and built public trust in the government. We also earned the confidence of the international partners and investors. Our rankings improved dramatically in Doing Business. In fact, in 2010, the World Bank ranked us among the ten most reformed countries in the world. We also recorded more improvements on the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Mo Ibrahim, Transparency International, and Freedom House and Afrobarometer indices.

In turn, we attracted considerable financial supports and foreign direct investments which we invested in building roads, hospitals, schools, and markets. We supported farmers with machineries and fertilizers, as well access to finance. We also increased public sector conditions of service and the minimum wage; restored pipe-borne water and electricity to many parts of the country, most which had not seen running water or electricity for over 30 years. Many parts of the country where people were spending days to travel to were now being accessed within hours. This hard work won the hearts of Sierra Leoneans, which made me win the election for a second-term mandate on the first ballot.

To a large extent, we maintained the same approach during my second term to the point that in 2013, the World Bank rated Sierra Leone as the fasted growing economy in Africa. However, that achievement was reversed by the outbreak of the deadly Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) in 2014. From a projection of Twenty-One Percent GDP growth, we ended up with a minus Twenty-One Percent. That was compounded by a drop in the prices in the World Market of commodities such as iron ore, which was then the mainstay of our economy. Nonetheless, we were able to put the economy back on a positive growth of five percent by the time I left office.

The work we did under my presidency gained me considerable popularity, and there were calls for me to run for a third term, which would have meant that I had to change the constitution, to hang on to power. I was not confused by those calls, as I knew that I had enjoyed a great privilege and blessing to have led my people for ten years and that it was time to leave. It is important to note that as a leader, people will provide all sorts of advice, but it is your business to analyse them and make the right decision.

Knowing and embracing my limits, we had elections organised, and I graciously handed over power and went to my home town in retirement. By the time I left office, Sierra Leone was rated the most peaceful country in West Africa and the third most peaceful in Africa by the Global Peace Index. Before that, the then UN Secretary–General Ban Ki-Moon had described Sierra Leone as a storehouse of post-conflict reconstruction and peacebuilding. To this day, where ever I go, citizens would show up in large numbers to thank and pray for me. There could be nothing more fulfilling than serving your people well.

As you can see, there is very good life after the presidency too. Not only that I am enjoying a lot of respect from my compatriots, I am also still having these and other international engagements to attend and contribute to. At the same time, I do sleep better; spend more quality time with my family, my grandchild, and hang out with my childhood friends.

Once again, democracy can work in and for Africans when leaders are elected into office based on their character, experience and track record and not mainly because of their ethnicity; when good governance and electoral processes are robustly monitored and backed up by early warning and early universally robust action; when the citizens are taken along and are given their say and role in the governance of the state; and when civil society deepen their role not just as watchdogs but critically so as in helping to shape public opinion and electoral decision based on facts.

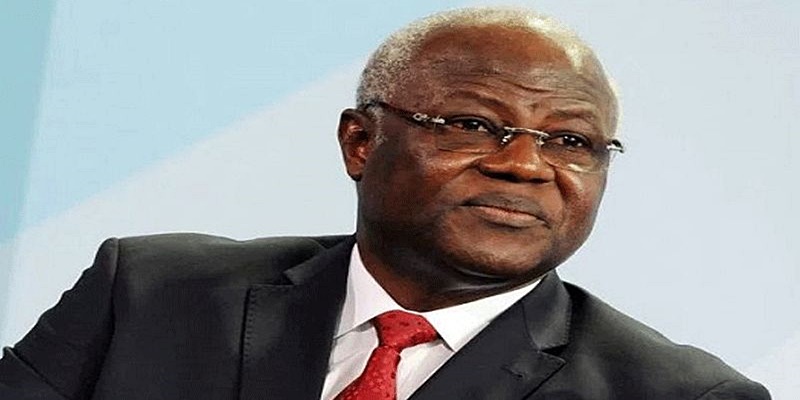

By His Excellency Ernest Bai Koroma,

Former President of the Republic of Sierra Leone.