What Happened to the Nigerian Intellectual Class?

Published on 8th September 2008

|

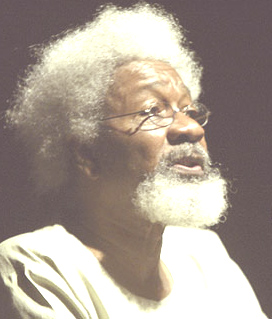

| Wole Soyinka, Nigerian Scholar |

In a formal sense, a few years after the University College of Ibadan was established in 1948, intellectualism, at least public intellectualism, became a feature of the Nigerian public landscape. And for the next three decades or so, Nigerian intellectuals were the doyen of the society; or at least, some of the doyens of the Nigerian society were intellectuals: men and women who earned the public’s trust, admiration and respect as a result of their faithfulness to intellectual pursuit.

From my own recollection and vantage point, most of the early intellectuals remained faithful to their craft. They were the purists, earning their living from the creation of their minds and brains; and were not voracious in their financial accretion. In addition, most detested party politics and also loathed serving in government -- especially military government.

The Ivory Towers and associated places, were their home; the place where they were most comfortable and productive. They were mostly poets and playwrights, lawyers and medical doctors, college professors and activists, socialists and communists and left-wing liberals. In some cases, they called themselves Comrades. They came in all shades and colors. They were educated at home and abroad.

The vast majority called the University of Ibadan, the University of Lagos, UNN, and the University of Ife, Benin and the University of Lagos home. Others were at the ABU and UNIPORT. A few others were independent scholars or were associated with Media Houses. Whatever their worldview was, and to whatever school of thought they belonged, they were interesting, inspiring, provocative, hard-hitting and sophisticated.

But beginning in the early 1980s, intellectualism began to take on a different shade and texture. There were new minds in town. The principal objectives began to change. This noble and august craft began to have different questions, different answers and different meanings. In a span of ten years, Nigerian-style intellectualism became unrecognizable.

And by the early to late 1990s, the society of Nigerian intellectuals had become mushy, clay-like, adulterated, corruptible, and puerile. It became a laughing stock. Some retained their stellar qualities, but for the most part, the society of Nigerian intellectuals became a pool of nothingness: a shadow of its pious past and now munching off of its past glory.

The intellectual class became as decadent and as rotten as the forces they had opposed for three or more decades. The military co-opted some; the bloody-civilians seduced others with money. The survival strategy employed by the military and the civilians was so effective it weakened the immune and defensive system of the Nigerian intellectual class.

Why and how the intellectual class came to be what it is today, is hard to tell. It is hard to come up with systemic answers without any kind of empirical studies. Here and how however, a few assumptions can be made. First, the military and their civilian counterpart were determined in their pursuit of the “enemies’” Achilles heels. They begged and cajoled; and wherever possible, offered inducements in the form of money, political appointments, overseas engagements, and phony think tanks.

In the end, this group of intellectuals simply rationalized their involvement by saying “it was better to fight from the inside than to be perpetual outsiders.” The belief here is that “change can only be effected from inside.” But we know of Nigeria that nobody that ever went in came out unblemished. The Nigerian system has a way of messing with ones soul and humanity. Once you go in, you can never return a saint.

Second, the strong-willed were threatened, blackmailed and prosecuted on fake criminal charges, persecuted, forced into exile, got fired or were demoted in their place of work. After several years of government brutality and criminality, some gave up the good fight. This accounts for why, in virtually all universities and research organizations in the world, there are Nigerians (mostly with clipped wings and mellowed disposition).

Those who dreaded life in exile -- and refusing to compromise their integrity -- simply gave up the good fight; faded away and died a slow mental and spiritual death. In the third instance are the black and despicable sheep: the wannabes, the fakes, and the bojuboju akowe. Unhappily, the membership of this group exploded when the Nigerian universities and the larger society was almost emptied of the first rates. It is why today, there are few bona fide intellectuals left in Nigeria.

Since the tail-end of the 1990s, the Nigerian intellectual class has consisted mostly of domestic and foreign government agents; political prostitutes; loud-mouths, contractors, academic-thugs, cross-dressers and Aba traders, and handout photo-copyists. The end goal of this class is money and political power. Their brand of intellectualism is mostly what Nigeria is all about today: all around poverty and idiocy.

To be relevant in today’s Nigeria, you may have to be a thief, an egregious liar, a thug, a cultist and a kidnapper. A child born within the last seventeen years may find it hard to believe that in the early and middle stages of our Republic, Nigeria boasted a sea of eminent jurists and medical doctors, diplomats and policy wonks, artists, teachers and university professors and those who took philosophy and the art of thinking seriously.

To say that intellectual pursuit is a dying art in Nigeria is not an exaggeration. There is a price to be paid for silence and cowardice in the face of oppression and injustice. In the same vein, there is a price to be paid by any nation or society that does not encourage intellectualism or intellectual pursuit. Such a society may regress, become stagnant, or spend all her years and resources imitating fluff from other parts of the world. Isn’t that what Nigeria is becoming?

That Nigeria can return to its vibrant past is not in question. What is in question are two significant questions: first, whether Nigeria has the political will to do so; and second, whether Nigeria hasn’t gone too far and too deep into the abyss for such a reversal, without incurring monumental and prohibitive cost.

Mr. Sabella Abidde, a PhD Candidate and SYLFF Fellow, is with Howard University Washington DC. He can be reached at: Sabidde@yahoo.com