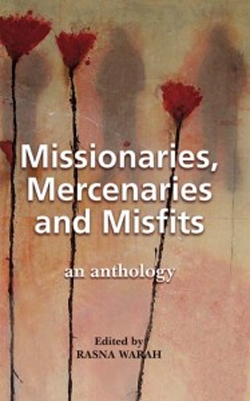

Missionaries, Mercenaries and Misfits

Edited by Rasna Warah. Milton Keynes (AuthorHouse) 2008, 199 pp.

At a first glance, the title of the book “Missionaries, Mercenaries and Misfits” promises a thriller, but no, the introduction enlightens us: it is about “the development myth”. Fourteen authors plus the editor, Rasna Warah, present their views on and experiences with the development business in Africa. The contributions are partly narratives or impressionistic expressions and partly academic statements. By that, they paint pictures of the development scene from different perspectives. But all are very critical towards ‘development’ and attack ‘development’ as an ideology and an industry. Rasna Warah refers to an interesting expression: “post-development”. (It reminds of the term “post-modern” - what ever that really means). “Post-development focuses on the underlying premises and motives of development” and at the end it is a rejection of ‘development’.

|

The original actors for development became the subjects of development; their ‘poverty’ became the main problem of development, forgetting their rights. In this context, Parselelo Kantai’s report on the Maasai demonstrations and invasions of 2004 in Kenya has to be seen. The Maasais claim the return of Laikipia to them and compensation for other land that was taken from them some one hundred years ago. In Laikipia, today 37 families of British origin own two million acres of land, on average 54,000 acres per family. However, the Maasais don’t get support from the government which is protecting Western interests.

All authors are touching on a topic that almost automatically comes up with development activities of the North in African countries: it is the relationship between the North and Africa. On the side of the aid workers, there is often love for Africa and Africans, and there is generous giving. But also, there is voyeuristic interest in slums that are offered as touristic sites. Even in the Millennium Village Project of Jeffrey Sachs, exemplified by Victoria Schlesinger’s visit to the village Sauri, there is a strong tendency that the programme is imposed on the people from outside, from ‘do-gooders’, in this case to the extent that Sauri is considered by neighbouring communities to be the “most hated village”. Development activities result in an objectification of Africans; they are not equals, they are not “in the driver’s seat”. Sunny Bindra states that the donor-dependent relationship weakens both sides - through loss of kindness and tolerance on the one, through loss of dignity and self-respect on the other side. And Philip Ochieng criticizes the notion of negritude that has been adopted by Africans because it “was no more than self-degradation, self-denigration, self-surrender to every form of insolence that the white man has heaped upon the black person for centuries”.

In the context of the ‘development industry’ big organisations are strongly criticized. Isisaeli Kazado considers the UN to have a culture of sycophancy, mediocrity, inefficiency and corruption. UN is bureaucratic, overdoing it with meetings and reports and duplicating programmes. Achal Prabhala and Onyango Oloo question the World Social Forum; its organizers and participants are considered to be “navel-gazing, self-referencing civil society globe-trotters”, “mouthing platitudes about social justice, debt eradication, gender equality, youth empowerment” etc.

In general, the Non Governmental Organisations come under the same force of attack by the authors. In Kenya alone, there were 3,000 to 3,500 NGOs active in 2007, employing about 100,000 Kenyans. Lara Pawson considers NGOs as a mechanism to carry out “imperial foreign policy”, turning receivers of aid to dependent victims; often they act as a “surrogate state”, replacing the government, while Onyango Oloo mentions “cynical NGO types” who are hijacking and co-opting the ideals, struggles and aspirations of real social movements. Five “silences” have to be considered in the NGO discourse according to Issa Shivji: (1) The anti-state stance of the donor community pushed the upsurge of NGOs; (2) There are three types of NGOs: politically, morally and personally motivated ones; (3) African NGOs are donor-funded; (4) Advocacy NGOs are doing government jobs; (5) The NGOs’ success is measured by “strategic plans” and “log frames” how efficiently they are managed and not which constructive input they give. NGOs have to choose between national liberation and imperialist domination, between social emancipation and capitalist slavery.

Mainly these last statements are based on a one-sided socialist tendency of some authors. They do not appreciate the positive contribution of quite a few NGOs and other organizations to development by uplifting the standard of living of the poor, by training farmers or ‘jua kalis’ of the informal sector and even by strengthening the rights of citizens. At the same time, the harsh criticism is justified, though selective. However, mainly readers of the North should appreciate the relatively wide spectrum of the development ‘business’ that is covered by the contributors to this anthology. It is definitely wider than, for instance, Moyo’s “Dead Aid” which focuses on ‘big aid’ and economy only. They should carefully listen to the arguments of Africans and of those of Asian origin living in Africa. For, the development ‘business’ or ‘industry’ in deed is a worrying phenomenon, serving its own purposes but not development.

NGOs are only part of this ‘industry’. Others are the governments and big organisations in the North, the governments and “appalling leaders” in Africa, the individual aid workers and last but not least the so-called beneficiaries. All of them contribute to a distortion of what should be the objective: development. Unfortunately, the authors of the book hardly give a hint what ‘development’ should be in a positive sense; and they tend to blame the North alone for the failing development aid. What have Africans to do for the change of the ‘development ideology’ and of the development industry? The whole ‘development myth’ would be finished and disappear when Africans and their governments would say: we are responsible for ourselves! - as NEPAD has announced. The authors might also ask themselves what they have to do, what they could do, beyond their grumbling criticism. But it seems to be a sign of the contemporary situation of development aid and development co-operation: there is a big helplessness. In this situation, the book really provokes critical questions.

By Helmut Danner,