The African's Influence in the New World Part 2

A lecture delivered for the Minority Ethnic Unit of the Greater London Council, London, England, March 6–8, 1986. It was addressed mainly to the African community in London consisting of African people from the Caribbean and African people from Africa.

Now, let's get on to the African's inventive mind. The preface to all of this is to deal with the free African craftsman in the Western world and how these craftsmen became free, that is, "free" with a question mark!

In the Caribbean where Africans were brought in large numbers, once they were taken over by the British and others their condition as an enslaved people was exploited. A class of Englishmen who had earned no considerable respect in England, came to the Islands as mechanics. Because their white face was a premium and because they were given privileges and guns and land and had access to African women, they considered themselves as belonging to the exploitive class. They literally exhausted themselves. But the Englishmen did not have the skills they found were needed on the islands and they began to disappear, physically, due to death from exhaustion or return to England.

The African craftsmen began to replace them. We now see the beginnings of the Africans' inventive mind in the Caribbean Islands. The same thing was happening in parts of South America. Many times, the English would bring over English-made furniture and there were some termites in the Caribbean. Some of these termites are still there, and when the termites began to eat up the soft wood in the English-made furniture, the African with his meticulous mind began to duplicate that furniture with local hard wood. This was done especially in Jamaica where they had large amounts of mahogany then. Jamaica does not have mahogany now because the mahogany forests were over-cut to the point where Jamaica now has no considerable variety of mahogany. Some of the most beautiful mahogany in the world used to come from Jamaica.

As with the disappearance of the British craftsmen, when the African craftsmen began to emerge, something else began to emerge in the Caribbean Islands. A class of people whose crafts maintained plantations. The Africans saw how important they had become and began to make demands. This is the origin of the Caribbean freeman. These freemen were free enough to communicate with other Africans, free enough to go back to Africa, and free enough to go to the United States. These freemen from the crafts class began to mix friendship with another group of freemen in the United States.

Now, how did the freemen become free in the United States? Mostly in the New England states where the winters were so long that it was not economically feasible to support a slave all year round, when they could be used only for four or five months. Slavery would have been just as brutal as it was in the south if the weather permitted. In New England the slaves had become industrial slaves. A large number of them were employed as ship caulkers. In the era of wooden ships, every time a ship came in the caulkers would have to drill something in the holds of the ship to keep it from eroding and to keep it from leaking at sea. A large number of Africans became ship caulkers, industrial slaves and they began to learn basic industrial skills. Professor Lorenzo Green's book The Negro in Colonial New England is specially good in explaining the details of this transformation during the period of slavery.

There were also slave inventors, but these slaves could not patent their own inventions. They had to patent them in the name of their masters.

Soon after the latter half of the nineteenth century, when the Africans understood that emancipation was not the reality they had hoped for, they began another resistance movement in the hope of improving their condition. They set up a communication system with all the slaves. There were no "West Indians," no "Black Americans." These were names unknown to us in Africa. We were and we saw ourselves as one people, as African people.

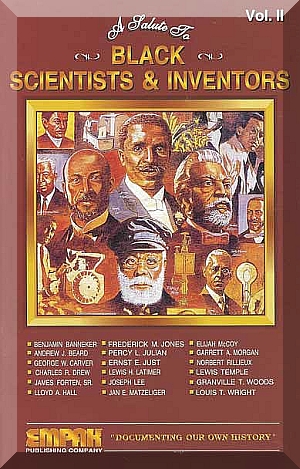

In the nineteenth century, the Africans began the inventive period. Before the beginning of the twentieth century, Africans had already invented some things that made life more comfortable for many in the United States. When you study a list of the numerous inventions of Africans you will find that they would invent things first and foremost to make life better for themselves. Benjamin Banneker was the first notable Black inventor.

When the Africans arrived in the United States, in 1619, the year before the Mayflower people arrived, they were not chattel slaves, but indentured slaves. Indentured slaves worked so many years and then they were free. Most of the indentured slaves were whites. Many times whites and blacks did not see the difference in their lives. They were both exploited, and they both had to work so many years before they were free. Therefore, during this time, there was a period when Africans and whites saw no difference in their plight and this was before prejudice and color difference would set in.

Many times they married one another and nobody cared; they were both slaves anyway. Out of these marriages came some people who helped to change the condition of the slaves in the United States. Benjamin Banneker was a product of one of these relationships. In his mother's time, if a white woman had a Black lover and because of her whiteness she worked her way out of the indenture ahead of her lover, then she came and bought him out of the indenture and married him. No one took noticed.

Benjamin Banneker, literally, made the first clock in the United States. He dabbled in astronomy, communicated with President Thomas Jefferson and asked Jefferson to entertain the idea of having a secretary of peace as well as a secretary of war. He was assistant to the Frenchman L'Enfant who was planning the City of Washington. For some reason L'Enfant got angry with the Washington people, picked up his plans and went back to France. Benjamin Banneker remembered the plans and is responsible for the designing of the City of Washington, one of the few American cities designed with streets wide enough for ten cars to pass at the same time. This was the first of many of the African American inventors that we have with good records. There will be many to follow and I am only naming a few.

James Forten became one of the first African Americans to become moderately rich. He made sails and accessories for ships. During the beginning of the winter of the American Revolution it was noticed that the tent cloth they were using for the tents was of better quality than the cloths they had in their britches. James Forten, the sail maker, was approached to use some of the same cloth to make the britches for the soldiers of the American Revolution. These britches, made by this Black man, saved them from that third and last terrible winter of the American Revolution. Now, the role of Blacks in the American Revolution is another lecture in the sense that 5000 Blacks fought against the United States on the side of England in the American Revolution, and the English had to find somewhere for them to go after the war. They sent some of them to Sierra Leone, but some of them went to Nova Scotia.

Jan Ernest Matzeliger, a young man from Guyana, now called Surinam invented the machine for the mass production of shoes; this invention revolutionized the shoe industry.

In summary, African Americans continued to create inventions. They revolutionized the American industry. For example, Granville Woods not only revolutionized the electrical concept, but he laid the basis for Westinghouse Electric Company. Elijah McCoy invented a drip coupling for lubrication that revolutionized the whole concept of lubrication. He had over fifty patents to his credit and so many whites stole from Elijah McCoy that anytime a white man took a patent of lubrication system, or anything that related to it to the patent office, he was asked, "Did you steal it directly from McCoy or did you steal it indirectly from McCoy or is it the real McCoy?" This is how the word came into the English language, "the real McCoy."

To be continued

By John Henrik Clarke

Courtesy AfricaWithin.com