Africa's Human Resource Needs Servicing

|

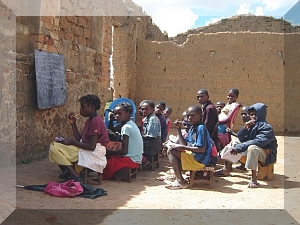

| A classroom in Bie, Angola Photo courtesy |

This was certainly why the international community recognized and agreed that education would be accessible to all only if it became a matter that concerns us all. The objective of providing basic education for all children, youths and adults throughout the world appealed to the entire world and captured the imagination of all nations. This was one of the main conclusions of the World Conference on Education for All (EFA) in Jomtien in 1990, and a series of summits confirmed it during the decade. The idea was reaffirmed in the form of six major objectives at the World Education Forum, held in Dakar in April 2000.

In fact, the Dakar Framework for Action stated, among other objectives, that by 2015, all children of primary school age should have access to free education of good quality and that gender disparities regarding education should be eliminated. That same year, the Millennium Development Goals were adopted, two of which, namely, Universal Primary Education (UPE), and the elimination of gender disparities in primary and secondary education, were defined as crucial for the eradication of extreme poverty. Consequently, basic education was officially recognized as the cornerstone of the global strategy for reducing poverty in the world by half in less than one generation.

From April 2000 to February 2010, nearly a decade after, where is Africa as regards these objectives? While remarkable progress was made concerning some of the EFA objectives, the different statistics on the mid-term evaluation of Education For All by 2015 reveal some worrying shortcomings. In view of current trends, unless there is an extraordinary surge of action, all the objectives of this programme will not be attained by 2015.

The analysis of the educational system in Africa shows a number of dysfunctions which, inter alia, could be summarized as follows: serious scarcity of teachers at all levels of education (for basic education alone, we need nearly 2 million teachers); poor capacity of infrastructure to accommodate learners; environment that is hardly conducive to research and innovation and inadequacy of resources allocated by our States to education.

Furthermore, in the last few years, priority has been given solely to basic education to the detriment of other levels of education. And yet, in this century of fierce competition, Africa cannot be satisfied with minimum knowledge, that is, primary level of education.

Learning from the results of the First Decade of Education for Africa, and noting the limitations of Education For All, in January 2006, the Heads of State and Government of the African Union launched the Second Decade of Education for Africa (2006-2015).

The Plan of Action of this Second Decade of Education for Africa highlights the following seven priorities: Gender and Culture; Education Management Information Systems; Teacher Development; Tertiary Education; Technical and Vocational Education and Training; Curriculum, and Teaching and Learning Materials and Quality Management.

The Second Decade of Education for Africa calls for the consideration of education as a coherent whole where each level of education, from kindergarten to tertiary education, vocational and technical training, including adult education, plays its full role.

It is becoming increasingly clear that in order to achieve the Millennium Development Goals, Africa needs doctors, engineers, professors and teachers, among others. In short, well trained professionals. This can only be done through the revitalization of African universities, as well as higher teacher training colleges or colleges of education.

For this reason, the African Union Commission is in the process of establishing tertiary education and scientific research as one of the principal pillars of the new architecture for the development of the African continent, alongside the peace and security pillar, where we cherish the hope of seeing our people live safe from fear and need.

Among the projects of the African Union Commission in the education sector is the Pan-African University, which aims at endowing Africa with productive research institutions and a critical mass of engineers and researchers in five fields that are relevant for its sustainable development, namely: space sciences; water and energy sciences (including climate change) ; basic sciences, technology and innovation; life and earth sciences; governance, humanities and social sciences.

Africa has for some time now, decided to anchor its development on education. For a country or a continent, there is no greater wealth than well-trained human resources.

By H.E. Mr Erastus Mwencha,

Deputy Chairperson of the African Union Commission.