Informal Cross-Border Trade: Friend or Foe?

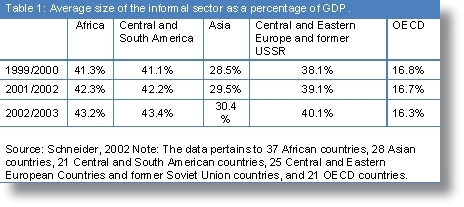

No economy in the world is without an informal component (see table 1).However, this sector continues to receive negative reception, especially, among Economists. This negativity is characterised not only in the lack of a universal definition of the sector, but also in the various names it has received under attempts to define it. The sector has been defined as: unofficial, underground, hidden, invisible, shadow, parallel, second, unregulated, unrecorded, black-market, moonlighting, unmeasured and unobserved economy.

An important component of the informal sector is the informal cross-border trade (ICBT) since its effects do spill-over between any two trading countries. As there is no agreed definition, the term "informal cross-border trade" as is used in this paper refers to imports and exports of legitimately produced goods and services (i.e., legal goods and services so that we immediately delink it from trade in unlawful/illegal goods), which are directly or indirectly escaped from the regulatory framework for taxation and other procedures set by the government, and, as such, often go totally or incorrectly unrecorded into official national statistics of the trading countries.

The EAC Partner States have a rich history of cross-border trade; much of which continues to be conducted informally. However, since the commencement of the EAC Customs Union in 2005, several policy pronouncements have promoted trade integration by increasing formal trade links. This has sometimes meant fighting and coercing the informal sector to formalise their activities or face punitive charges. Incidentally, it is the formal firms, those that informally transact big volumes and high valued trade across borders, that cause a lot of harm to EAC economies as opposed to the many small informal survivalist firms and individuals who are trying to eke a living out of ICBT to realise such basic rights as access to food, shelter, education, clothing and health that their government cannot afford.

Key Characteristic of ICBT Practice

Who are involved and how do they practice ICBT?

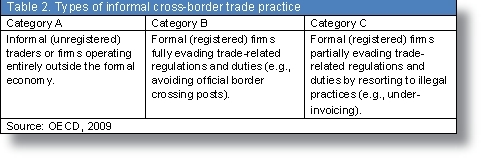

The participants in the ICBT are both from informal and formal firms. Mostly, the informal firms operate entirely outside the formal economy and most of the goods they transact attract little or no custom duties at all as they largely originate from within EAC.

|

On the other hand, the formal firms handle large of volumes non-originating goods that attract custom duties, but they practice ICBT by passing the commodities through “unofficial routes,” thus fully evading trade-related regulations and custom duties; others partially evade these regulations and duties by involving in illegal practices such as under-invoicing (i.e., reporting a lower quantity, weight or value of goods so as to pay lower import tariffs), misclassification (i.e., falsifying the description of products to qualify for nil or lower tariffs), mis-declaration of country of origin to avoid associate tariffs and regulations, and/or bribery (see table 2).

|

What are their education level, gender and age?

A majority of the players in ICBT are aged between 20-40 years; 44.2% have attained secondary education and 25.8% have professional/semi-professional diploma and certificate. Those with diploma, certificate and degrees are 10% but their number is rising by year, which indicates two things: one, cross-border trade is increasingly becoming more sophisticated, requiring better education to survive in it; and, two, most graduates these days are jobless and have no starting capital to pursue formal business; thus, an increasing number of them resort to informal employment including ICBT.

What goods do they trade?

All types of goods are involved: staple food commodities and even food aid that have a direct impact on regional food security; low quality consumer goods such as shoes, clothes, textile and vehicle and bicycle parts and even fake drugs; and, some of the goods reflect the same ones that benefit from government export promotion schemes, such as textiles; the latter ones are sneaked into the domestic market duty free.

Mode of ICBT transportation

The main modes of transport used are vehicles, bicycles, head/hand, motorcycles, animals (donkeys), push carts, boats/canoe etc. People with disabilities riding on wheel chairs are also involved to move small but valuable products such as sugar, salt, soap, cooking oil and plastics.

What volumes do they handle?

The flows of ICBT goods appear to be in small quantities. Where big consignments are involved, they are usually divided into smaller quantities to avoid attention when passing across borders. But, since these small quantities are passed repeatedly, they end up being significant. The small quantities passed across the border are not necessarily sold immediately; they are piled in jointly-owned stores until a reasonable volume is reached and the players jointly hire means of transport to haul them to their final destinations.

What are the key factors that fuel the growth of ICBT?

The growth of ICBT represents a normal market response to the presence of physical and technical barriers in formal trade which significantly increase the cost of both joining the formal economy and operating within it. The incentives inherent in ICBT also promote its own growth but to some traders it is the socio-economic constraints that hinder their beneficial engagement in formal trading. Corruption, too, plays a factor in fuelling the growth of ICBT; those who are able to make ‘facilitation payments’ have their clearance expedited and, sometime, without proper control checks. This rent-seeking attitude means that officials who are posted at the border stations are considered fortunate to the extent that some bribe their way to be posted at the border. Traders who cannot ‘facilitate’ the expedited clearance process are exposed to robberies at night when they have to spend unplanned nights at the border towns as there are also no decent affordable accommodation.

Other important push factors towards ICBT are based on the weak economies of EAC that has seen formal employment shrink. The rising rural-urban migration in search of often non-existent employment also leads people to the informal sector employment. Together, the low wages and underemployment in the formal employment also push people to look for alternative ways to supplement their meagre wages, where ICBT has been one such alternative.

Conclusions and Recommendations

ICBT still represents a significant proportion of regional cross-border trade in EAC. Lack of such an important data as on ICBT implies that what has always been stated as GDP of EAC economies is often grossly underestimated. That means there have been wrong perceptions about the actual trade balances of EAC economies with each other, the trade benefits that have accrued to Partner States from regional integration, and, the extent of the performance and direction of growth of regional trade in EAC. Consequently, wrong policy prescriptions may be prescribed, leading to unintended negative results such as diversion of resources away from important projects, thus impacting negatively the regional trade integration and development of EAC.

To solve the problem of ICBT, the government should approach it by dealing with the factors that drive its growth and not fighting the traders who are merely eking a living out of the business. What would be important is to establish for the sector an enabling environment with measures that will reduce its negative impact on the economy.

Creating a supportive environment for the informal traders could be the start of a successful process of formalisation of the informal traders. This will enable the countries to collect better information of the goods, values and quantities traded amongst them hence improving the planning and decision-making of the EAC countries. In addition, the EAC countries will be able to increase revenue collection across borders to finance their national development as the need for traders to smuggle goods will have been reduced; and lastly, to the EAC countries, there will be more goods produced in the EAC countries, more employment and more people earning an income, thereby improving the standards of living in all the EAC countries.

To the ICBT players, creating conducive environment for their trade may mean better knowledge of the trader about their rights as they trade across the region, hence cases of paying bribes to border officials and smuggling goods across borders will be reduced. The trader will also benefit from payment of the correct amount of taxes (where taxes still apply) as opposed to the current case where they are sometimes charged duties on goods that are not supposed to attract any duties. Cases of harassment of the trader and seizures and loss of goods will be reduced. Lastly, the cost and time of clearing the goods will be reduced resulting in lower prices of goods and higher earnings for the trader.

Deliberate efforts must be made by EAC governments to first develop a common definition of what constitutes informal sector such that it can be well targeted with appropriate policies. An inventory of the number of informal traders including the trends of growth of the sector must be undertaken and a common threshold for determining and classifying it set. To end the stigmatization of ICBT, it is important that EAC governments start to encourage and promote trade exhibitions involving informal traders across EAC borders.

In all the processes recommended above, it will be important to involve civil society organisations in formulating and implementing such policies. There is need to undertake aggressive publicity and dissemination of the EAC Treaty, the CU Protocol, the Community’s policies and other applicable laws and principles as provided for under Article 39 of the Protocol. There is need also to educate government agencies on the CU Protocol including attitude change among customs officials and other border officials who continue to collect tax on duty-free goods and those seeking rent from ICBT, and monitor compliance.

Culled from a Policy brief prepared by Victor Ogalo, Programme Officer at CUTS Africa Resource Centre, Nairobi.