GMOs: Which Way for Africa?

|

| Photo courtesy |

The Protocol contains reference to a precautionary approach and reaffirms the precaution language on Environment and Development. The Protocol also establishes a Biosafety Clearing-House to facilitate the exchange of information on living modified organisms and to assist countries in the implementation of the Protocol.

Biosafety describes measures used for assessing, monitoring, and managing risks associated with GMOs. These are plants, animals or microorganisms that have had DNA inserted into their cells from another organism. The direct in-vitro transfer of DNA between or within species is referred to as genetic modification. It is expected that embracing GMOs will promote increased food harvests and therefore, a natural mitigation for food shortage. Considering the below-average rains being experienced in many regions and the looming famine, this should be good news.

Touting GMOs as the silver bullet for food scarcity is nothing new. Governments in Africa, including Kenya, that are exposed to recurrent food insufficiency are under increasing pressure to adopt GM technology. The passing of the Biosafety Act was characterized by open lobbying by pro-biotechnology multinational giants against determined proponents of conservative, ecologically-sustainable agriculture practice. Eventually, the pro-GMO camp prevailed. However, it was apparent that genuine debate on the merits and demerits of the GMOs had been subverted by powerful, vested interests.

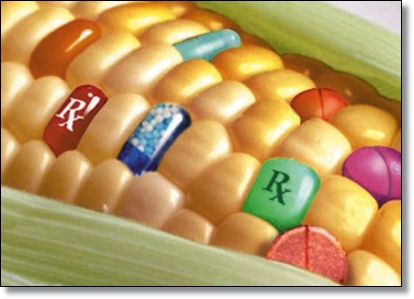

For poor nations, whether or not to adopt genetically modified products is hardly an objective decision for governments and farmers. Rather, it is presented as take-it-or-perish doctor's prescription! The argument goes that, by planting high-yield GMOs contrasted to the traditional variety, food sufficiency would be guaranteed. This would lead to attendant benefits such as a healthy citizenry and improved quality of living. Besides, governments would find profitable alternative use for the huge amounts spent in importing food.

The real truth is less charitable. Rather, it is rooted in a pernicious and often secretive marriage of big business to government. Peering through debates in media and other forums promoting adoption of GMOs, it is apparent multinational companies under the protection of home governments are spending fortunes to market GMOs in Africa.

But why would the US government, for instance, spend so much resources promoting GMOs? The official answer is painted in generosity: that it is championing science and technology to boost food production and, therefore, food sufficiency in a hungry Third World. GMOs are portrayed as the miracle cure to hunger. Who owns this technology? Who has the control rights for GMOs? A few companies nicknamed the "Gene Giants" dominate global sales of seeds.

Take for example the Genetic use restriction technology (GURT), colloquially known as terminator technology, a name given to proposed methods for restricting the use of genetically modified plants by causing second generation seeds to be sterile. The technology was developed under a cooperative research and development agreement between the Agricultural Research Service of the United States Department of Agriculture and Delta and Pine Land company in the 1990s, but it is not yet commercially available. Because some stakeholders expressed concerns that this technology might lead to dependence for poor smallholder farmers, Monsanto Company, an agricultural products company and the world's biggest seed supplier, pledged not to commercialize the technology in 1999. However, customers who buy seeds from Monsanto Company must sign a Monsanto Technology/Stewardship Agreement. The agreement specifically states that the grower will not save or sell the seeds from their harvest for further planting, breeding or cultivation. This legal agreement pre-empts the need for a "terminator gene."

These "suicide seeds" have not been commercialized anywhere in the world due to an avalanche of opposition from farmers, indigenous peoples, NGOs, and some governments. In 2000, the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity recommended a de facto moratorium on field-testing and commercial sale of terminator seeds. The moratorium was re-affirmed in 2006. India and Brazil have already passed national laws to prohibit the technology.

Take-it-or-perish: Seed trade is big business valued at KSh1.9 trillion. The aggressive pursuit of seed business by gene giants poses important moral issues. It is evidently prompted by a realization of the power of the seed. Farming exclusively depends on seeds. Majority of the local farmers own and control their seeds. They grow their own crops from seeds they have saved from previous harvests. They make decisions concerning seed storage, sharing, replanting as well as redistribution. By contrast, GMO seeds are patented.

Rushed embrace of GM technology could disenfranchise farmers through patenting of naturally-occurring genes. It could lead to licensing and therefore controlling seeds that would normally be freely retained and sown the following season. This "patenting of life" could lead to an unacceptable control and commercialization of natural resources. Sole dependency on GM seeds has the potential to create a private monopoly over plants and seeds that would likely be priced way above ordinary farmer purchasing power.

Considering the cost of GMOs inputs against the purchasing power of ordinary farmers, it makes sense to promote credible alternatives. In the interests of sustainable farming, farmers should be encouraged to continue using seeds of known source with proven yields. The Kenya government should seriously consider subsidising seeds, not as an episodic bout of generosity, but as a sustained agricultural policy. Whether GMOs are the solution to food scarcity is debatable.

With introduction of GM seeds aimed for sale, the cost of farming will certainly rise and leave local farmers poorer. Farmers should be advised to retain/revert to alternative agro-ecological agriculture, which is sustainable, less costly and environmental friendly.

There are a myriad available opportunities for bringing in clean food/maize that should not give us sleepless nights if the reasons for importation are genuine. Before we advise Kenyans 9and by extension Africans) to go ahead and consume GMOs because they risk starvation to death due to Climatic Changes, there is need for adequate information for informed choices to be made. As much as we need to embrace technology, let us remember that nuclear power too if handled properly has immense potential but in the hands of the ignorant, its adverse effects last for generations!

By Maryleen Micheni

Programme Officer, Research and Information Management

Participatory Ecological Land Use Management Association - PELUM Kenya.