Zimbabwe Elections: Entrepreneurship vs Employment

|

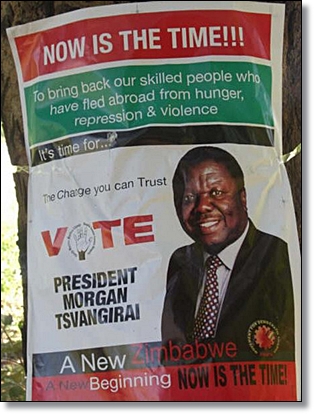

| A campaign poster in a previous Zimbabwe election |

Our parents’ generation aspired to become lawyers, doctors, teachers, and engineers – persons of standing in society. The political party advocating employment would seek to broaden the opportunities for people to access these jobs.

On the other hand, the party pushing for ownership and entrepreneurship believes that Zimbabweans must ensure that their children are educated to aspire to run law firms, set up medical practices, create engineering firms from scratch and build schools and centres of excellence – in short, become owners and entrepreneurs rather than CEOs. Ergo, change makers and economic drive-chains rather than economic cogs.

The flawed and yet popular misconception amongst the pro-employment crowd is the belief that potential foreign investors will be deterred by the 51% local ownership requirement, thus rendering ownership useless and stifling job creation and growth. ''Why would I take my money to Zimbabwe and only have 49% control and profits?'' is the common refrain. Unfortunately, in politics, appeals to fear usually sell better than those to reason.

For a start, there are many extremely successful and wealthy investors that own far less than 50% of the corporations they invest in. For instance, Warren Buffet, who is widely regarded as one of the US’ most successful investors with a net wealth in excess of $50 billion dollars, does not own more than 50% of any corporation with a threshold over $500,000.

Secondly, according to the UNCTAD - the United Nations' trade body - the profitability of foreign companies in Africa, and Zimbabwe particularly, has been consistently higher than in most other regions of the world.

For every dollar a British or American corporation puts into Zimbabwe they get $0,41c profit per year. After Indigenisation, these corporations get $0,20c on the dollar. This is still far higher than the $0,09c average in their home countries. For a nation with the world’s best climate, over 47 exploitable minerals and a highly educated populace, the nation’s profitability is simply too good to resist. Indigenisation will not deter investment.

The pro-employment party also argues that Zimbabwe needs to sell its capital assets to foreigners in order to "balance its payments." There is a wise old proverb about beggars and choosers they say. It is like a once wealthy family selling its antique furniture and silverware in order to maintain its lifestyle. Unfortunately, when a country sells off its capital assets, it negatively affects its current account balance down the road as increasing "rents and dividends" flow out of the country.

The pro-ownership party wants these rents and dividends to flow directly to employees and communities. In fact, $2bn dollars worth of Community Trusts for local development are being rolled out across the country to ensure as much. Employee Share Schemes will put $205 million dollars directly into Zimbabwean worker's pockets by way of shares, which they will pay back with rising share prices and dividends.

Giving all employees a chance to own a stake in their company can be a unifying, productivity-boosting strategy; however, making shares available only to a few select privileged foreign investors is neither smart politics nor smart economics.

The US National Centre for Employee Ownership found that, on average, employee-owned firms grow 8-11% faster than their peers. Clearly, encouraging ownership not only creates more worker-shareholders but more workers in general.

However, the ace up the indigenisation programme's sleeve and the reason why it is a stronger hand than 'investment-for-jobs' is neither the community trust, nor indeed employee or direct share ownership. The trump card is the National Indigenisation Fund’s plans to stimulate new and small business growth by promoting entrepreneurship, especially amongst women, youth, the underprivileged, disabled and orphans.

In today’s global knowledge-based economy, entrepreneurs play a vital role in creating new companies, commercialising new ideas and just as importantly, engaging in sustained experiments in what works and what does not. Zimbabwe’s best way to be globally competitive and create jobs is not foreign investment or lower prices but new ideas.

Entrepreneurship is a powerful force for doing good as well as doing well. In fact, a small number of innovative start-up companies account for a disproportionately large number of new job creation. Home grown start-up companies spin off subsidiaries, provide experience to employees who then decide to go it alone, and nurture dozens of suppliers.

According to UNCTAD's recent Foreign Direct Investment in Africa: Performance and Potential Report, the single biggest driver of job creation on the continent has been local entrepreneurs- not foreign direct investment.

Local ownership and entrepreneurship creates jobs, fosters new industries, boosts small business and ensures that Zimbabweans have the lion’s share of an ever growing economic pie. On the other hand, reliance on foreign investment artificially fattens the pie. Zimbabweans may benefit from the odd piece of the pie here and there by way of employment. But eventually, the foreign owners of that pie will repatriate rent, dividends and profits leaving Zimbabweans back to square one.

In a matter of months, Zimbabweans will go to the ballot and choose which economic vision they believe best squares the circle.

By Garikai Chengu.

Garikai Chengu is a research scholar at Harvard University's Faculty of Arts and Sciences. Visit his website: http://www.garikaichengu.com/