ANC: Beyond the Centenary

|

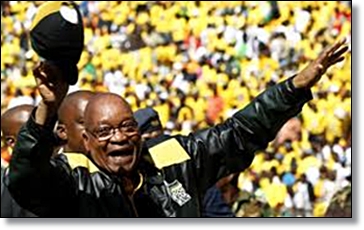

| President Jacob Zuma acknowledges supporters P.Courtesy |

In his 08 January 2012 President Jacob Zuma spoke of an ANC that has been born out of a call for unity in diversity. In the same speech the President dealt with the heroic anti-colonial and later anti-apartheid struggle the ANC has waged against both a distant and a resident coloniser. The narrative remains authoritative in the ANC’s scheme of historical events and should be lauded, as has been, by South Africans.

The position of the ANC as leader of the liberation movement is thus inscribed unto the tombs of South Africa’s history. The movement’s ability to galvanise broad support for its course beyond racial and sexist lines towers its 100 year story thus far. The flexibility with which the ANC was able to adapt its policy trajectory to be in line with the dictates of history got crowned by its adoption of what would otherwise have become a document of democrats irrespective of political affiliation, the Freedom Charter. The charter’s declaration that ‘South Africa belongs to all who live in it’ remains one of the inherently potent forces that enrolled the human rights community onto the correctness of the ANC’s quest for a liberated South Africa.

In pure historical terms the ANC formation predates the Bolshevik revolution of 1917 and many other global nationalistic movements including its longest adversary the then National Party of South Africa. The formation of the ANC is thus part of the centennial band of South Africa’s constitutional history and nationalist reawakening as evidenced by the adoption of the 1910 Constitution and the formation of the National Party in 1913. The De la Rey led rebellion of 1913 as well as the Sol Plaatjie led peaceful deputations to the colonial government creates a South African nationalistic space that developed along two paths with 1961 marking the first anti-colonial milestone and 1994 finishing the nationalistic urge, albeit with a crystal divided nation.

The inherent ability of the movement to have navigated its struggle years amidst a hostile Cold War inspired bi-polar world represented by the USA and Russia, as well as a concretising growth of right wing economic thought that dominated much of the 20th century attests to its intellectual resilience and therefore the human resources it commanded. Having survived two active world wars, two economic depressions, a communist revolution in Russia, countless anti-colonial wars as well as a variety of technological shifts that continue to redefine world outlook, the ANC stood the test of its previous time. The ‘all who live in it’ glue that culminated in the historic 1994 enfranchising of all South Africans remains one of the inheritance the founding fathers of the movement bequeathed to future generations.

Since countries and societies are locked into a development path by their historical past, the ANC, and by extension South Africa, can therefore not wish away its colonial and apartheid past as a template for all manner of discourse on the construct of the beyond struggle future. The call for the current crop of ANC leaders and intellectuals to appreciate the complex historical conditions that created some of the social, cultural and economic templates that are instructing to the post 1994 democratic RSA, is one of the vexing challenge for creating a context for the next 100 years. This call should however be contextualised around the need to reduce, and not eliminate, the growing sovereignty of party political preference at the expense of voter sovereignty.

The growing dearth of futuristic discourse on South Africa at the altar of party political aggrandisement for practitioners of politics has not only reduced the ANC’s political mobilisation base along historical lines but also sharpened the inquest on post-struggle thinking within the ANC. The in-ANC code for post struggle thinking is concretising at least around the concepts of ‘modernisation’ and ‘generational mix’. These concepts are fast representing the chronic generational divide bedevilling the 100 year old movement. Given that political situations will always arise out of disagreements, even if ‘a society’ have in common their membership of it and their acceptance of certain rules which enable it to hold together; the post centennial ANC needs to re-emerge both in ideological and organisational terms.

The historical glues of Colonialism and Apartheid that focussed the in-ANC diversity never meant that the inherent diversities of the conglomerated civil society formations constituting the ANC-led liberation movement were settled. If diversity is truly the keynote of social condition and opinion, the differential character of in-ANC individual or factional interests will be enough to ensure that the movement is never uniform. The textural changes being experienced by the ANC both as a result of it being a non-biotic organism and an entity that is grappling with how it institutionalises itself in the new arena of politics, government; are recreating its character as redefined by emerging diversities of condition and opinion. The price of liberation politics has historically been known to be government, although such histories have variously contextualised conditions ranging from outright war victory to constitutional accords that are designed be accommodative of the political balance of forces.

In its 100 year history, the in-ANC constituencies have been defining the various destinations of the National Democratic Revolution in a manner that made the liberation movement’s journey to be inextricably linked with residues of past politics. At its inception it galvanised around basic franchise for all and mutated through to demanding a variously defined ‘better life for all’. In this continuum of heroic struggle a diversity of general outlook developed form the vestiges of a broadly defined ideological premise only defined as ‘South Africa belongs to all who live in it’. The degree to which constituencies that ‘live in South Africa’ are able to muster an ideological pre-eminence at a given historical epoch will be based on the active diversities the political system is ‘consenting’ to embody as national interests.

The interest disequilibrium that has, and at the beginning of South Africa’s constitutional democracy, led to the development of a two stream and yet potent nationalist reawakening as represented by the erstwhile national party and the ANC; remains the most foregrounded residue of the centennial anti-colonial struggles of the sub-continent. The national party’s own ‘anti-colonial’ democratic breakthrough victory of 1948 that got crowned with the 1961 Republican Constitution defined a ‘volk-based’ development trajectory that systematically refused that ‘South Africa belongs to all who live in it’ and thus crafting a definite ideological orientation that built a ‘nation-state’ (‘a volk-state’). The gradualised repudiation of the exclusionary nature of the ‘white consensus’ state did not only generalise the liberation interests of the ANC but pluralised the individual interests of in-ANC constituencies via a growing elite amongst the African majority.

It is in the pluralisation of these interests that a ‘general conflict of interests’ has developed over the 100 year history of the ANC. The 1949 ANCYL inspired ideological rapture in respect of the conduct of struggle, the 1955 defiance campaign, the 1961 decision to form Umkhonto we Sizwe, the mid 1960’s decision to collaborate with the Apartheid state by former ANC leaders such as Kaizer Matanzima, the 1973 and beyond radicalisation of the trade union movement, the 1976 June 16 student uprisings and the1980’s ungovernability calls as well as the recent ‘economic freedom in our life time calls; define the innate conflict of interests characterising the ‘broadness’ descriptor for the 100 year old ANC.

Without vitiating the ANC’s experience and capacity to manage its conglomeration of civil society interests through its long held congress alliance platform, it needs to migrate towards a post-liberation struggle mind set. It needs to start operating as an organisation ‘rooted in its liberation history but not restricted by it’. Its identity should not only generate pride for its members, but for South Africans. It must become the political vernacular that creates social pride to its beneficiaries to an extent that ‘the sheer plasticity’ of ANC-ness ‘defeats the ever growing attempt to blind its meaning to any one camp of being South African.’

The muted and growing nervousness by ‘ivy-school educated’ and ‘upper class’ members of the ANC’s historical and primal constituencies when associated with the liberation movement calls for a redefined ANC-ness. The centennial euphoria that is underpinned by a policy and an elective conference of the ANC provides an opportunity to redefine a new socio-political trajectory for the ANC.

Having bequeathed the preamble of the Freedom Charter to South Africa through its entrenchment in the Constitution, the ANC should during its policy conference isolate those aspects of its political mobilisation arsenal for further bequeathing to South Africa. The ability of the ANC to define, for instance, national holidays and heroes such as Nelson Mandela, Solomon Mahlangu, Vuyisile Mini, Oliver Tambo, Bram Fischer and others as a South African Heritage will go a long way in defining the emergent ANC. The incomplete aspects of the 1996 constitutional accord can best be championed by the ANC as the incontestable nexus of socio-political and economic life of South Africa. The space for maverick politicking can only be contracted by the ANC’s definition of a South Africa of 2112. The 2012 ANC Conference must adopt a January 08 speech for the 2112 ANC President and committing the next generation to complete the puzzle for that speech to be read without any reservation.

By Dr FM Lucky Mathebula

Fellow at UOFS Centre for African Studies.