True Sustainable Development

|

| Photo courtesy |

There is no question that humans must take care of the environment and use resources in a way that preserves them for future generations. However, this must not comprise the ways in which billions of people could and should lift themselves out of poverty. Tackling pressing environmental issues requires human solutions, and to achieve this end, people need to be healthy, well housed, and educated. Therefore, sustainable development cannot be achieved by merely focusing on the environment alone; it must place the person at the center. That way even “green economy” will have a sensible meaning, as it is meant to meet human needs.

And let’s face it, poverty pollutes too — it pollutes not only the environment but also health, education of the poor, and, consequently, development itself. The international energy agency estimates that around 1.3 billion people, almost 20 percent of world’s population, do not have access to electricity. Most of these people rely on kerosene at best, wood or charcoal at worst, for lighting. According to the World Health Organization, indoor air pollution caused by the above methods of lightning results in 2 millions deaths every year. Children from households without access to electricity won’t have access to quality education. Insufficient access to sources of lighting impairs reading and will, in return, hurt the future potential and productivity of these young minds. Shifting to efficient energy sources that are less harmful to human health is paramount to environment protection. It also means huge improvements in the social and economic well-being of the world’s poor. This should be central to the business of Rio+20. Saving the environment through the “green economy,” the new mantra for economic sustainability, requires highly developed economies to give it a try. The proposed “green solutions” of solar panels, biofuels, and wind turbines are simply out of reach for poor countries. Though they might be alternative sources of energy in the future, with increased technology, they remain unaffordably expensive for “the bottom billion.”

Germany, the world’s top producer of solar energy, is said to have spent 130 billion dollars, financed mainly through government subsidies, for energy worth 12 billion dollars. This was possible because Germans have, broadly speaking, met their basic needs. How many countries can afford such luxury?

The inability of billions of humans to meet their fundamental needs, including access to clean and sanitation, nutrition, basic health care, housing, and education, mean an inability to protect the environment. The anticipated Sustainable Development Goals (to replace Millennium Development Goals when they expire in 2015) need to facilitate and not hinder ways in which all people can and should meet these basic needs. Fortunately, this is in line with protecting the environment, too. With those needs met, each person will have the ability and responsibility to engage in environmentally friendly practices.

For Rio+20 to be meaningful, it has to begin with the basics: the real human needs of people and the recognition that every human person (especially the young), when properly invested in, has the potential to solve economic and environmental problems. There won’t be the “future we want” if the concerns of the majority of the earth’s inhabitants are not given top priority. Yes, we need to protect the environment, but most importantly, people should be allowed to use available tools to climb out of the poverty hole. This will not result simply in access to electricity and quality education, but will also give them new tools to better protect the environment. This means that countries such as Ethiopia, Ghana, Nepal, or Haiti should be allowed to build dams and even use fossil fuels to provide electricity to their people, without “green noise,” the objections you hear in poor countries when they engage in projects deemed environmentally unfriendly by rich countries and NGOs.

People in developed countries worry more about environmental issues, even as they are affected less by them. But for over a billion people surviving on less than $1.25 a day, those worries are luxuries they can’t afford. To achieve that status, the poor need to meet their basic human and economic needs — in order to think about the environment. It’s just human nature to worry about food and shelter before worrying about anything else.

The rich prospered without worrying about the environment; why restrict the poor from using accessible and affordable tools to take the same path? To reach green targets, developed countries are trying to offset the burden of their own carbon emissions onto the developing countries, even when they cannot achieve the targets themselves.

In addition, the world’s growing population must not be seen neither as a burden to environment nor a figure to be reduced but rather as a tremendous potential to be tapped in order to save the environment. It is ironic that rich countries still consider other people a threat to the environment while they grapple to reverse declining populations at home.

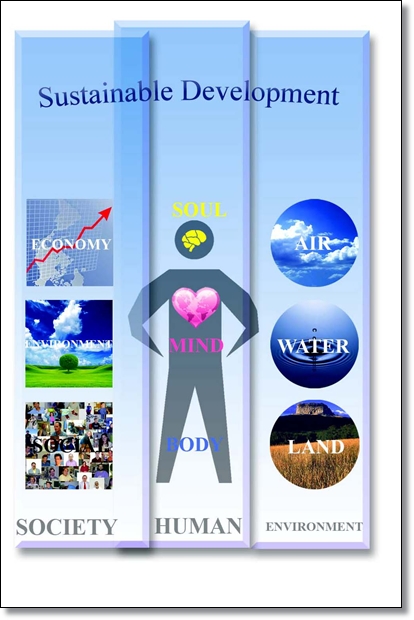

Economic and social development are major concerns for the majority of humans, and should not take a back seat at Rio+20 and other subsequent policy-setting meetings. Understanding the interdependence of the three pillars of sustainable development and the central role of human persons in addressing the environment will determine whether Rio+20 fails or succeeds in meeting human needs of today and tomorrow.

By Obadias Ndaba.

President of World Youth Alliance, an international organization with consultative status with the United Nations and European Union, among other institutions. First published in National Review