Kenya’s Health Sector and Politics : A Sociological View

|

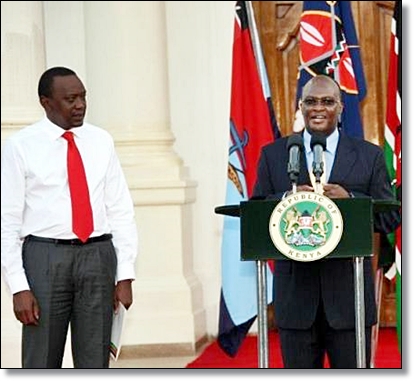

| President Uhuru Kenyatta & James Macharia P. Courtesy |

Critiques against the doctor’s protest, included among others, the media, the government spokesperson, the National Nurses Association of Kenya (NNAK) and the Kenya National Nurses Union (KNNU). The representative bodies of nurses state that medical professionals should focus on rendering their professional services in the already burdened health system severely lacking in core healthcare service personnel rather than get bogged down with administrative duties, the latter which the nurses unions reiterate should be left to professional managers. They believe that Mr Macharia’s banking and accounting experience is crucial in reforming the ailing health sector by organizing human and financial resources while unlocking the sector’s value which in turn can greatly boost health services.

Contrary to the stand taken by the KMA, the Union of Kenya Civil Servants back the President’s nomination noting that Mr Macharia need not be a medic per se as his managerial skills will be supplemented by medical professionals notably the Chief Medical Officer, Chief Nursing Officer and Chief Pharmacist. Despite such stances, the KMA has called for an extraordinary meeting of its general council to press for their opposition, despite the fact that the vetting of the Cabinet Secretary nominees is the business and prerogative of the Parliamentary Committee on Appointments.

The scenario presented above is not new within the discourse of health sociology. Health sociologists observe that since politics is about power played in the process of resolving conflicts, winning over opponents and allocating scarce resources, medical dominance is the power of the medical profession in terms of its control over its own work, the work of other health workers, health resource allocation, health policy and the way in which healthcare is organized and managed.

In any healthcare system, the role of government remains a contested issue where health policy and the organization of health care tend to reflect an ideological struggle between economic and social liberalism, the former on efficiency of resource allocation by the market, and the latter on the rights to healthcare benefits. Historically, within such a system, the key feature of the medical profession is one of autonomy with regards to the medical profession’s authority to direct and evaluate the work of others without being subject to formal direction and evaluation. This authority is socially legitimized, granted and guaranteed by the State through legislation and constitutional amendment, the latter that has created a problem regarding self-regulation of the medical profession. Hence the professional has been able to retain its autonomy economically (determine pay), politically (right to make policy decisions as legitimate experts on health matters) and clinically (right to set professional standards of practice including resource allocation and the work of other health care workers).

As a dynamic process however, this dominance has been contested through processes of deprofessionalisation and proletarianisation. The former refers to a general theory predicting the decline of medical status and power due to increasing health education of the public and increasing public distrust in the management by medical professionals, while the latter refers to a theory that predicts a decline of medical power as a result of deskilling and the salaried employment of medical professionals. Proletarianization in effect results in a loss of economic independence by doctors in terms of control over their work due to managerial authority and bureaucratic regulations.

While the two trends challenge the discourse on medical dominance particularly in terms of medicine’s economic and political autonomy, sociologists caution that neither processes can adequately encompass emerging trends in public health systems, hence a new concept emerges, that of managerialism. This concept better explains the challenges to medical dominance and is deemed appropriate to understand the Kenyan scenario presented above. According to scholars, managerialism is rooted in the goal of the ‘right of managers to manage’ and thus presents an ‘acceptable face of new-right thinking regarding the state, namely that of better management, a label under which private sector disciplines can be introduced to the public services, political control strengthened, budgets trimmed, professional autonomy reduced, and even the possibility of public unions being weakened. These changes can be explained in terms of pressures of global capitalism and international markets on the nation state itself that brings a rupture to the customary relations between the state and the medical profession.

Kenya’s case illustrates how medicine is treading from professional domination of its own sector to a state-constrained corporatism. The political desires of the state, the lobbying of numerous ‘non-medicine’ health occupations, and public clamour therefore coincide in producing state regulatory constraints and, in many cases, direct public representation on previously ‘autonomous’ professional self-regulatory organisations.

Kenya’s new appointment is a process of social change that challenges two core features of the medical profession: the centrality of professionalism and medical dominance. When hit by intense changes, healthcare systems tend to weaken their long established core characteristics, such as the crucial role of the professions and medical dominance. Is it then the decline of medical dominance in Kenya? Not so, bearing on a study in the UK by Judith Allsops (2006) who notes that despite limits to medical autonomy due to shifts by governments towards competitive markets, and state-sponsored regulatory meant to boost performance, the medical profession will continue to play an increasingly important role at least because of the socio-cultural powers inherent in medicine.

Scholars thus warn that since the state/medical profession alliance is so entangled, the former must move carefully so as not to damage its own interests by politicizing established areas of expertise. Moreover, there remains strong public support for the products of medical knowledge which also limits the scope for government action to curb professional powers. We shall thus observe KMA’s action/reaction in this regard!

By Satwinder S. Rehal

The author is a health sociologist by training and an Associate Professor in the Department of Consular and Diplomatic Affairs, De La Salle College of Saint Benilde, Manila, The Philippines, and is also an Honorary Teacher in the School of Population, Communication & Behavioural Sciences, University of Liverpool (UK).