Extraction and Exploitation: The Case of Paladin’s Kayerekera Uranium Mine

|

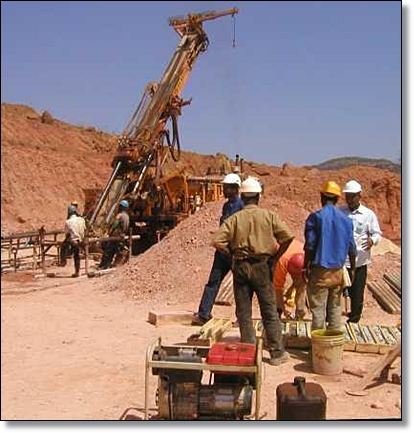

| A Mine in Malawi P. Courtesy |

It is worth noting that for a long time, mining did not play a significant part in the Malawi economy. Nevertheless, following the discovery and eventual extraction of mineral resources like coal and uranium, the future looked bright. The country was expected to maximise economic benefits from such extraction. Such benefits would accrue in a number of ways including the diversification of the economy and the considerable expansion of industrial employment.

The case of Paladin’s Kayerekera Uranium Mine in Karonga District, northern Malawi shows that such expectations are vain. There is maximum uranium production alongside massive exploitation because of such factors as non-payment of taxes, unfair agreements between Paladin and the Malawi Government, and the engagement of expatriates in jobs that are saturated with local expertise.

Paladin Energy’s subsidiary, Paladin Africa, is mining uranium at Malawi’s largest mining project at Kayerekera Mine in Karonga District. The Malawi Government has a 15 per cent stake in this company of Australian origin. Records show that Paladin Africa has recorded a rare 20 per cent increase in production in 2013 compared to 2012. In fact, in June 2013 the mine recorded an annual production of 1,344 tonnes of uranium oxide, a record production at Kayerekera Uranium Mine since production began around 2009. However, in reaction to such reports, Paladin Africa’s General Manager (International Relations), Greg Walker, maintains such records are a mere assertion and, instead, argues that the mine continues to operate on losses. No wonder some people are counter-arguing that such statements are misplaced and are merely aimed at minimizing taxation payments by Paladin Africa to the government.

In a 2013 report called “The Case of Kayerekera Uranium Mine,” a Zimbabwe-based African Forum and Network on Debt and Development (AFRODAD) cites the disproportionate benefits of private sector mining and resource extraction. Precisely, the report states that the Government of Malawi has (already) lost billions of Malawi kwachas (local currency) from royalties, resource rent and value added tax within the three years that the Kayerekera Uranium Mine has been in operation. “We recommend that the Government of Malawi should renegotiate the contract with the Australian Company, Paladin Africa, on the uranium mining,” argued AFRODAD’s Executive Director, Collins Magalasi, who compiled the report ahead of the 33rd Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) heads of State Summit. The latter was held in Malawi’s Capital City, Lilongwe, in mid-August 2013.

On the growing public dissatisfaction on the secrecy surrounding the terms and conditions of the Kayerekera mining contract (and on the need for renegotiation), earlier in 2013 Paladin Africa is said to have indicated that Kayerekera is a done deal: that it cannot be renegotiated until the expiry of the ten-year period of the current contract. This is not surprising since we are talking about economic interaction between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots,’ the latter have always been powerless. This has deep-seated historical origins. In this current scenario, Paladin Africa has capital with which to mine uranium in Malawi (not in Australia) and, on the other hand, the owners of the land (owners of uranium) have inadequate capital. Is this enough reason to tolerate something glaringly nonsensical in the twenty-first century? Factually-speaking, who is supposed to be negotiating for a fair deal (popularly dubbed a win-win situation nowadays) between the two sides?

In this connection, in 2011 Dr. Perks Ligoya, former Governor of the Reserve Bank of Malawi ‘scorched’ the Kayerekera Uranium Mine deal by arguing that Malawi gave out ‘a lot of concessions and funny conditions’ to Paladin Africa. As expected, obviously in self defence, the company responded that Kayerekera was a “high risk investment” and concessions to the company (by the Malawi Government) reflected the company’s role as a “pathfinder.” What an insult and impudence!

It is worth noting that, according to Magalasi, the challenges facing Malawi’s extractive industry are in no way exclusive to Malawi as they apply to many African countries. With reference to Malawi, the report further indicated that there are also weak regulatory frameworks, for instance, in environmental management coupled with lack of personnel to inspect and enforce regulation on health and the environment. For instance, water and air pollution that results from accumulated mineral dust dumping currently poses a serious health hazard to the local people living in the area.

On the creation of industrial employment for Malawians, Paladin Africa is not supposed to engage expatriates to fill jobs that locals can do. This would probably have made sense if this were the colonial period when, common knowledge tells us, there were relatively fewer qualified Malawians in various fields. Unfortunately, this is not just the post-colonial period, but the twenty-first century at that! In fact, according to the Ministry of Trade, Malawi’s expatriates’ policy emphatically states that ‘foreigners should not replace Malawians.’

It is perturbing to note that the practice on the ground is quite the opposite. In June 2013 there were stark revelations in the print and electronic media that the mining company had employed foreigners to work as chefs, welders, ordinary mechanics, stores and warehouse officers, and name them. Yet there are a lot of trained, experienced and competent Malawians who can ably fill such positions. Just to drive the point home, one of the many institutions training chefs capable of working at any level is the Malawi Institute of Tourism (MIT). In this case, would it be wrong if one argued that the local populace are not adequately appreciating the presence of the mining company within their country, generally, and within their locality, as far as the people of Karonga District are concerned?

It has further been learnt that some of these so-called expatriates are working illegally at the mine since they do so without the Temporary Employment Permits (TEPs). As if this is not enough, yet others are using Temporary Residence Permits (TRPs) that have outlived their lifespan. A good number of them are said to have used their TRPs for over two years despite the (Malawi) Immigration Department explicitly stating that “a TRP, which lasts six months, can only be renewed once”. On this issue, the Immigration Department is partly to blame by indicating that it conducts routine checks ‘subject to availability of resources’ to verify the status of the expatriates. In this case, may be it is lack of capacity and down-to-earth monitoring mechanisms that are compounding this, otherwise straight-forward, issue.

Arguably, the scenario between Paladin Africa and the Malawi Government regarding the mining deal would historically be likened to what used to happen during the slave trade era in Africa, that is, up to the 19th century. During this period, foreigners could confront a ‘village’ and would demand from the ‘village headman’, thus: “we want you to provide us with strong, able-bodied men in exchange for alcohol (moba), cloth (vitenje), and beads (majuda). If you do not act as we demand, we will have no alternative apart from raiding your village”. The ‘village headman’ had to oblige, otherwise raiding, indeed, followed. There was, then, the direct threat of use of coercion. Everybody knows this was savagery! But the question is: why should a similar phenomenon continue in a civilized world?

It is important to realize that what I have presented is the superficial (on-the-surface) but realistic view of the situation at Kayerekera Uranium Mine in Karonga, northern Malawi. I have merely glided over the issues due to space and time. I am sure that the officials at Paladin Africa would be at pains accepting the issues that I have raised. Why? Truth hurts (unenesko ukubaba)!

Before I pen off, a word of free advice to the Malawi Government – as a harbinger running errands on behalf of the populace (the owners of the land), there is need to appreciate that times have changed. In Malawi we are now almost two decades into the democratic governance period during which elected governments are expected to do one thing: govern on behalf of the owners of the land! Obviously, what is currently happening is far from what Malawians hoped for when they were ushering in multi-party politics in 1994. If I may be allowed to go back a step further in the past, I would categorically state that whatever malpractice Paladin Africa is currently engaged in had no space in the regime of late President Dr. Hastings Kamuzu Banda, founder of the Malawi nation (Chata wa fuko la Malawi), also famed as the ‘destroyer’ of the ‘stupid’ Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland (M’bwanganduli wa Chitaganya)!

By Harvey C.C. Banda.

The author is a Lecturer in African History in the Department of History at Mzuzu University in Malawi. His areas of specialty are migration and development; and social and economic development (African history).