Uganda Needs No Constitutional Crisis

|

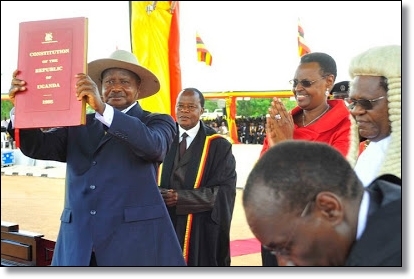

| President Museveni displays the Constitution Photo courtesy |

The tittle of this paper admits the fact that there is no constitutional crisis in Uganda- although it goes ahead to expressly suggest the necessity for it! The tittle also markets a view that a constitutional crisis is necessary to ameliorate gaps and challenges faced by institutions in Uganda’s oil economy- and broadly, the entire body politic. I must say, for sure- the author is aggressively imaginative, and provocative although I also belong to the worldview that Intellectual curiosity is good for Uganda’s transformation agenda.

Uganda is a Constitutional Democracy: The 1995 constitution is a sacred living document. It breathes in and out. It has life. This life is enshrined in Chapter 1, Articles 1, 2, 3 and 4 (Sovereignty of the people, Supremacy of the Constitution, Defense of the Constitution and promotion of public awareness of the constitution) and Chapter 18: Amendment of the Constitution (done by parliament or through a referendum): The 1995 Constitution entrenched the democratic principle of separation of powers with an independent Judiciary and all powerful Legislature with powers to verify and veto the Executive. Whether these institutions are exercising their solemn constitutional powers and mandates is indeed a matter of debate and Uganda’s citizenry have the power to whip or dismiss those that are not fulfilling or exercising their constitutional mandate to the expectations of the people.

Why should there be a constitutional crisis when the Constitution puts all the power in the hands of the people – and also prescribes how to deal with circumstances that warrant changes in the constitution from time through people’s representatives or by people themselves through amendment by means of a referendum? The necessity of a constitutional crisis is a far off the mark and possibly a wild mirage. In this discussion, I will deal with what I find to be key provocations in the author’s summary shared beforehand.

The Economic Transition in 2022

Unless the author has a crystal ball, and looks into the future with rose-colored or rather tinted spectacles, I will excuse his forecasting – because 2022 is not far and those who will be alive, will validate or face the reality of the author’s predictions. Uganda has not only seen real economic transition but also economic consolidation since 1986. This will go on even beyond 2022. The NRM record in maintenance of excellent monetary and fiscal policies that continue to enable the economy to remain resilient to external shocks has kept inflation low.

In 1986, Uganda’s economy was a paltry US$ 0.246 billion in size, now it is US$ 21 billion (the economy has expanded more than 81 times since 1986). In 1986, tax collection was a miserable 5 billion shillings; it is now 7,000 billion shillings. In 1986, Uganda was generating only 60 MW and had a kWh per capita of 28, now Uganda has installed power capacity of 812 MW. In 1986, roads were in a pathetic state, the NRM has since done a total of 1,355 kms of new tarmac roads and repaired 1,621 kms of old tarmac roads since. In 1986, Uganda was receiving 98,405 tourists, now the country welcomes 1,151,356 tourists.

In 1986, infant mortality was 122 for every 1,000 children born alive. Presently, it is 54 per 1,000 born alive. In 1986, the average life expectancy was 43 years of age, now it is 50.4 years for both female and male (See – World Bank Datasets, 2012 UBOS statistical abstract and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) world fact book)- And by the way, on the ‘thorny’ issue of tackling poverty, Uganda, under the National Resistance Movement (NRM) is comparatively not doing badly.

According to the latest International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank (WB) Global Monitoring Report 2013, Kenya’s poverty headcount stands at 43.37 per cent against Uganda’s 38.01 per cent using the poverty cut-off point of $1.25 per person. Tanzania stands at 67.87 per cent; Rwanda poverty stands at 63.17 per cent while in Burundi it is at 81.32 per cent. The poverty level scoring was based on the number of people living below $1.25 a day.

Although the numbers above show progress in socio-economic transformation, challenges still exist, for instance no mother should die while giving birth and indeed 38% of the population drenched in poverty is something we should not celebrate. But what these numbers also tell us – is that positive socio-economic transformation is happening. Uganda is indeed not Portugal or Greece, the two most pronounced Economies in Europe that are facing a both economic, financial and political crises.

The National Debt

At the end of FY 2012/2013, the total stock of Uganda’s public debt (domestic and external) was UGX 15,938.1 billion or 29.1% percent of GDP. Any nation state whose debt as a percentage of GDP is below 60 is considered to be in a good position. Countries like the United States of America (USA) have a national debt stock of 89% and they are still running. The important parameter is debt sustainability and not debt stock. Indeed debt should be sustainable and Uganda is doing a good job on this.

Uganda’s debt structure can be looked at from the loan negotiated terms such as repayment period, grace period and interest rate. Uganda’s biggest debt (86.6%) is concessional and owed to multilaterals where interest rate is less than 1% payable over 40 years. This money is deployed into projects and programs that build the capacity of the nation to pay the debt. Such projects include electricity generation and roads. Money is not spent on consumption.

We should therefore not look at debt as a stock, but rather look at its capacity to redeem itself. For example, in 2002, the size of Uganda’s economy was UGX 12 trillion (GDP) and now it is UGX54 trillion (GDP current market price) meaning that the economy multiplied 4 times in a space of 10 years. This means that borrowing has partly contributed to the expansion of the economy, with capacity to meet debt obligations and continue growing. The expected oil revenues, will in effect substitute Domestic debt (which is characterized by high interest rates and short repayment terms), reduce domestic interest rates for the private sector and enable the economy to consolidate investments in infrastructure as a critical enabler and stimulant of the economy. This is how oil will partly help the economy.

The‘projected’ political Transition in 2022

Transition to another political party? I don’t see this happening, because in spite of challenges, NRM continues to offer the best concrete and practical hope to Ugandans. It remains the only party that captures the imagination of citizenry. Indeed, if you look at the 2010 and 2011 Afrobarometer opinion surveys, 78 percent of Ugandans believed that Uganda’s situation was getting better – under NRM. That is why President Museveni won the past elections across all regions of Uganda with an unchallenged whopping 68 percent. Is this going to change in 2022 because of oil? I don’t think so – because the NRM government continues to pursue pro-people reforms. The most critical of all, in my view is cutting down the veil of secrecy and working towards open government and inclusiveness.

Defeating corruption through democratization of information (Information entropy) – Making oil work for all Ugandans.

With access to information, citizenry will have the capacity to challenge and engage officialdom and make it more accountable. This officialdom includes executive, parliament, local governments, political and Statutory and other bodies such as the Inspectorate General of Government (IGG), Police, Authorities and companies. Here is the benchmark - In 1996, Rivtva Reinikka and Jakob Svensson in a study tracked how much of the capitation grant reached the schools. The figures from the survey teams that went to the schools were then compared with the computer records of the releases. The answer they got was nothing short of stunning. Only 13% of funds ever reached the schools. More than half of the school got nothing at all.

Inquiries suggested that a lot of the money most likely ended up in the pockets of district officials and bureaucrats. When these results were released in Uganda, there was an uproar. The finance ministry started publicizing the releases in the main national newspapers. By 2001, when Reinikka and Svensson repeated their school survey, they found out that the schools were getting, an average 80% of the discretionary money that they were entitled to. About half of the school head teachers that had received less than their entitlements initiated formal complaints and eventually, most of them received their money. There were no reports of reprisals against them or against newspapers that ran the story. It seems the district officials had been happy to embezzle the money when no one was watching but stopped when that became more difficult.

These Uganda headteachers suggest an exciting possibility: If rural schools head teachers could fight corruption, perhaps it is not necessary to wait for a change of government or profound transformation of institutions for better policies to be implemented. The foregoing shows that careful thinking and access to ferment of information driven through the wider media and community platforms has potential to check and stop corruption.

Now, apart from publishing releases, the Ministry of Finance Planning and Economic Development (MFPED) has launched an online budget information portal – follow your money via - http://budget.go.ug/.

We have over 228 FM radio stations – broadcasting in local languages and with millions of listeners. If Radio Kigezi in Kabale announced that NAADs procured and is delivering 90 bulls to a list of named farmers in one week, assuming they don’t arrive, beneficiaries will start trekking to the office of NAADs coordinators and for sure, nobody would divert these bulls. Such is the power of information in mitigating corruption. Therefore, liberating information on oil revenues and making information to the public available will ensure efficient utilization of oil resources and deepen participation of citizens. The government is also studying international covenants like Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) and Open Government (OGP) with the view of signing up and delivering on commitments.

Conclusion

I hope the fears raised by Angelo’s remarks have been rested. In future, I hope we will have time to discuss how the oil economy will further deepen inclusive growth, lower the cost of doing business, fully transform agriculture and speed up Uganda’s journey to middle income status – and eventually First World.

By Morrison Rwakakamba

Special Presidential Assistant – Research and Information

mrwakakamba@gmail.com