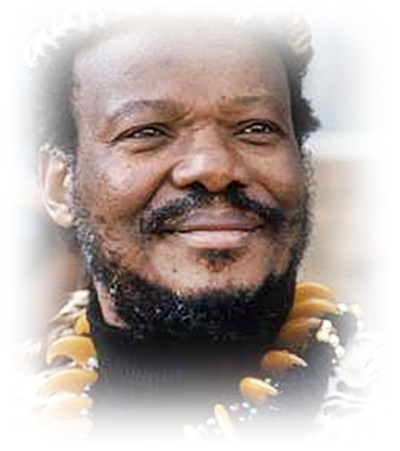

South Africa’s Liberation Struggle: Mangosuthu Buthelezi Perspective

|

| Mangosuthu Buthelezi |

South Africa’s liberation struggle did not begin in 1912, when my uncle, Dr Pixley ka Isaka Seme, founded the South African National Native Congress, the forerunner of the ANC. Neither did it start with the incarceration of Nelson Mandela. It began in the 19th century with the so-called Kaffir Wars; wars between the Bapedi people and other ethnic groups, like the Zulus.

In 1879, the powerful Zulu Kingdom that had emerged from those wars was destroyed by the British Army in the culminating battle of the Anglo-Zulu War. My great grandfather, King Cetshwayo, was exiled and his Kingdom was artificially divided into 13 kinglets. King Cetshwayo presented himself to Queen Victoria to plead our nation’s case and held discussions with Her Majesty’s Secretary for Colonies. But the King was brought back under impossible conditions.

With the Kingdom dismembered and new kings installed, war esued amongst the Zulus themselves. My grandfather, King Dinuzulu became embroiled in civil wars, which saw him exiled to the Island of St Helena, where several of his children were born, including two of my mother’s brothers, Prince Solomon and Prince Mshiyeni.

Upon his return from exile, King Dinuzulu found himself implicated in the Bambatha Rebellion of 1906. Inkosi Bambatha brought his wife and daughter to the King’s residence, seeking sanctuary for them, which the King granted. Consequently, he was charged with treason, convicted and jailed. This was shortly after the Anglo-Boer War between the English and Afrikaners.

While King Dinuzulu was still imprisoned, the predominantly Afrikaner provinces of Transvaal and the Free State, and the predominantly English provinces of Natal and the Cape, came together to form the Union of South Africa. In May 1910, General Louis Botha, an old friend of King Dinuzulu, became the first Prime Minister of the Union, and ordered the release of King Dinuzulu. The King, however, was kept in exile, where he died two years later.

King Dinuzulu was succeeded by his son, King Solomon, who sought the marriage of his sister, Princess Constance Magogo, to his Prime Minister, Inkosi Mathole Buthelezi. I am the product of that marriage. Another of King Solomon’s sisters married a young lawyer by the name of Pixley ka Isaka Seme, who, as I have mentioned, founded the South African National Native Congress on the ideal that reconciliation be negotiated into existence. Dr Seme was steeped in the struggle for the recognition of our Zulu Kingdom, and the struggle for our liberation as black South Africans.

The entrenched and increasingly institutionalised exclusion of black people in the subsequent years increased the momentum of our liberation struggle, till the point in 1960 when liberation movements like the ANC and the PAC were banned. Inkosi Albert Luthuli then sent Mr Oliver Tambo abroad to form the ANC’s Extended Mission-in-Exile.

I was, at that stage, actively involved in politics, having joined the ANC Youth League at the University of Fort Hare. I was mentored by Inkosi Luthuli and enjoyed friendships with leaders like the young Nelson Mandela. I thus maintained contact with Mr Tambo and met with him in 1963 en route to an Anglican Church Congress in Toronto, Canada. As a result, my passport was confiscated by the regime when I arrived back home, and was not returned to me for 9 years.

In 1970, the Nationalist Government passed the Homelands Act which saw the formation of nine self-governing territories. This laid the foundation of the grand scheme of apartheid to declare black territories independent, thereby depriving millions of black people of their South African citizenship.

While we vehemently opposed this fragmentation of our country, Mr Tambo and Inkosi Luthuli sent a message to me through my sister, Princess Morgina Dotwana, urging me not to refuse the leadership of KwaZulu if the people asked me to lead, for in this way we could undermine the system from within. I succeeded in doing this, for my position as Chief Minister of KwaZulu enabled me to block the plan of balkanization by refusing so-called nominal independence for KwaZulu.

I was also in a position to challenge the regime, to campaign for Mandela’s release, and demand the unbanning of political organisations so that we all could come to the negotiating table. In February 1991, when President FW de Klerk announced the imminent release of Nelson Mandela and other political prisoners, he acknowledged that it was I who had helped him reach this decision.

Despite all this, my role in our liberation history is seldom spoken of, and lies abound concerning Mangosuthu Buthelezi and Inkatha, because in October 1979 Inkatha and the ANC’s mission-in-exile faced an irreconcilable difference of opinion. A rift opened between us over the issues of the armed struggle and the call for international economic sanctions and disinvestment.

I could not advocate sanctions when the people in South Africa were asking me to oppose them, pleading that the loss of jobs would deepen their poverty. I could also not abandon the principle of non-violence upon which our liberation struggle was founded and I rejected the armed struggle. To me, bloodshed, violence and the loss of innocent lives ran contrary to my Christian faith.

The ANC’s mission-in-exile could not forgive our refusal to toe the line, and the deadly propaganda machine was turned against me. So effective was the decades’ long campaign of vilification against me that, even today, lies and misinformation are taken as historical fact.

Because I and Inkatha had such massive support, as the centre of political mobilisation within South Africa, we became one of the main targets of the ANC’s People’s War. The dynamics of the white-on-black and black-on-white conflicts are well known, and were highlighted through processes like the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. But the black-on-black violence that claimed some 20 000 lives in the eighties and early nineties has not yet been properly addressed.

I attended endless funerals, grieved in many homes and found myself targeted for assassination more than once. But throughout this low intensity, internecine civil war, Mandela and I stayed in constant contact. We had been together in the ANC Youth League and were family friends long before his incarceration. While in prison, he corresponded with me, often through my wife, Princess Irene. In the last letter he wrote to me from prison, just before his release, he expressed his anguish over the bloodshed and asked that we meet immediately upon his release to find a way to end the violence.

Unfortunately, Mandela was prevented from doing this by leaders of the ANC and UDF. A year passed before we met and many more lives were lost. Knowing of our friendship, a group of traditional leaders asked him why we had not met right away and he told them that his comrades had, in his words, “almost throttled him.” Such was the intense and blind hatred for me that years of propaganda had created.

In 2002, Mandela finally made this admission in public: “We have used every ammunition against (Buthelezi), but we failed. And he is still there. He is a formidable survivor.”

Let me speak briefly now about the effects of the strategies employed during the liberation struggle, for they continue to have an impact on our country today. From exile, the ANC called on students to boycott education and take to the streets. Young people were encouraged to cross the borders and train with Umkhonto weSizwe, the ANC’s military wing, founded by Mandela. They employed the slogan “Liberation Now, Education Later.”

I differed on this strategy, believing that education is a powerful tool for liberation, and knowing that we needed to prepare that generation to take the reins in a liberated South Africa. Inkatha juxtaposed the ANC’s slogan with “Education for Liberation.” In KwaZulu alone black schools opened on time and students were in class, learning to become competent citizens and leaders of integrity.

It still pains me to think of the generation of young people who inherited a liberated country, yet had little to contribute beyond entitlement, lawlessness and ignorance. That was the legacy of the armed struggle and the ANC’s willingness to sacrifice lives. The extraordinary levels of crime in South Africa also have their roots in the armed struggle. Today we are facing despicable crimes, like rape of the elderly and rape of babies; crimes which deeply affront our culture. The inculcated lack of respect for human life has had grave consequences.

The corruption and lack of integrity in leadership that our country struggles with today is in part also a legacy of the Machiavellian liberation strategies of the ANC. In KwaZulu, where I administered governance under the screws and indignities of apartheid, Inkatha advocated self-help and self-reliance. We received less from the State per capita than any other province, as punishment for my refusal to take nominal independence. Yet, in partnership with the people, we built many houses and clinics, and some 6000 schools.

When South Africa entered democracy in 1994, the IFP already had 19 years’ experience in good governance. In all that time, never once had a single allegation of corruption ever been levelled against my administration. So we brought to the Government of National Unity a leadership of integrity and experience.

The Government of National Unity was created by the Interim Constitution under which we ushered in democracy. In terms of that Constitution, any party receiving 10% of the vote gained a seat in Cabinet. The IFP won more than two million votes in 1994. President Mandela invited me and a few of my IFP colleagues to serve in his Cabinet for the first five years of democracy, and I became Minister of Home Affairs.

Although not constitutionally required to do so, President Thabo Mbeki asked me to continue in this portfolio in his Cabinet, which I did for another five years. This was somehow a concession, for President Mbeki had first offered me the Deputy Presidency of the country. However that was torpedoed by Mr Jacob Zuma and other ANC leaders in KwaZulu Natal, who insisted he make it contingent on my giving up the premiership of the province to the ANC. As a democrat, I could not do that. I respect the will of the electorate, who had voted for an IFP Premier.

President Mandela showed his respect for me on many occasions, which served the cause of reconciliation between our two parties. He was often out of the country fulfilling his role as an international mediator, and appointed me Acting President of the Republic in his absence on many occasions. President Mandela often joked that he was the de jure President, while Deputy President Mbeki was the de facto President of South Africa. It was a joke, but it rang true.

It was difficult for me to serve in President Mbeki’s Cabinet when he emerged as a denialist on the issue of HIV causing Aids. Aids is one of the gravest challenges our country has had to face. We have one of the highest incidences of HIV/Aids in the world, yet Government refused to give anti-retroviral treatment to pregnant women and new-born babies.

Thousands of lives were saved by the IFP’s intervention. We went to the Constitutional Court as amicus curiae in case that forced Government to roll out Nevirapine across South Africa. We had been doing it in KwaZulu Natal under an IFP-led Government and had already proven that it could be done both cheaply and easily.

The fight against HIV/Aids is personal for me. In 2004, I lost two of my children to the disease. At that time South Africans were still hesitant to speak about Aids and no one admitted that someone had died of the disease. It was a cultural veil of silence that needed to be torn down, rather than merely lifted. I therefore spoke at my son’s funeral and announced that he had succumbed to HIV/Aids. I did the same at the funeral of my daughter. I knew that we could only beat this pandemic by talking about it openly.

The following year, President Nelson Mandela lost his eldest son, Makgatho Mandela, to HIV/Aids and took the same bold step as I had. Together we led the way into a fight that South Africa at last could win.

Of course we still have a long way to go, despite the enormous progress that has been made in this and other areas. But, even in an election year, I am not one to say that Government hasn’t done anything for our people. I am not inclined towards rhetoric. I speak the truth, no matter how unpopular it makes me. The truth is, as much progress as we have made in twenty years of democracy, South Africa has yet to achieve full liberation. We have yet to attain economic freedom.

The poverty of our people and the disparities created by colonialism and apartheid run very deep, affecting our progress socially, politically and economically. But the greatest hindrance to overcoming these challenges is without a doubt corruption. Dishonesty in leadership and dishonesty in governance are taking a toll on our country. The Auditor-General’s Report paints a bleak picture of our municipalities, which are failing to deliver services. I appreciate the fact that there is not enough in our State coffers to eliminate the inequalities of the past. But much more could be done with what we have, were it not for money being stolen, mismanaged and wasted, from national government all the way down to local municipalities.

In this season of my life, I find I have become of necessity a champion of truth once again. I have taken up the fight against corruption and poor leadership, and will fight for integrity in South Africa for whatever time God still gives me on this earth. I am grateful that throughout my long life and my long career in politics I have been supported by men and women of faith. Brothers and sisters in Christ have held me up in prayer and encouraged me when the road became too long and too painful.

It is always a pleasure for me to speak about South Africa.

By Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi MP

President of the Inkatha Freedom Party and Traditional Prime Minister to the Zulu Monarch and Nation