Ebola: Avoiding Outbreak in other Parts of Africa

|

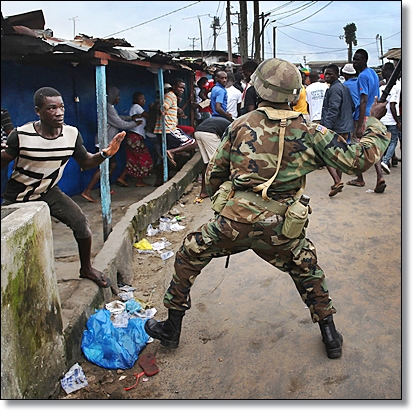

| A Liberian Army soldier enforcing a quarantine on the West Point slum. Photo courtesy. |

It is important to note that an unrelated “classic” Ebola outbreak, according to the WHO is ongoing in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). This seventh known outbreak since 1976 in DRC is relatively under control. Local and national health authorities have extensive experience managing these outbreaks in mostly rural, isolated parts of DRC and surrounding countries. However as I had noted in previous Ebola articles in this medium, the current 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa is affecting heavily populated urban centers and slums.

Keeping Ebola Out of the Rest of Africa

Todate, the robust response of Nigeria and Senegal to imported Ebola cases that led to WHO designation as Ebola-free countries is helping control further spread in West Africa. The lack of any known infection in two countries with relatively large populations - Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire - is another fortuitous circumstance. The aggressive, transparent response of war torn Mali to its few imported Ebola cases is also admirable.

The first obvious strategy is to continue ongoing global effort to contain and eventually end the Ebola outbreak in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. Containment efforts should in addition to clinical and public health responses, urgently address social and economic needs of affected families and communities. Food shortages, growing number of orphans, loss of life-preserving modest family incomes, breakdown of law and order, isolated communities, stigma and human rights violations deserve urgent attention. Ongoing global support from United States, the European Union, Cuba, China and the United Nations (UN) system should continue until the three countries become Ebola-Free. Other nations with infectious disease response expertise such as India, Brazil, Russia, South Africa, Egypt, Kenya and Ethiopia should ramp up support. Africans in the Diaspora need to have more significant impact on the ground. Improving coordinated logistics for skilled volunteers is critical.

Fortunately, the WHO and CDC suggest the Ebola outbreak is showing signs of slowing down in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, following reduction in the proportion of new cases per day. Whether these fewer cases are due to more deaths from Ebola or as a result of affected families shunning health facilities due to mandatory 21 day quarantine of contacts is unknown. Ending the outbreak would require all contacts of confirmed cases testing negative for the virus and a country recording no new cases within a continuous 42-day period. Efforts to address financial, clinical and logistic impediments are much better today in hard-hit countries compared to lack luster responses in early August 2014, according to the WHO and CDC.

The second strategy is to drastically reduce or at best swiftly stop spread of imported Ebola cases to densely populated West African countries of Nigeria, Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire, with a combined 2014 estimated population of 226 million, according to the World Population Review. A significant Ebola outbreak in these countries would be an ultimate public health nightmare with grave repercussions for West Africa, the rest of the continent and the world. For the moment, none of these countries have current Ebola infections as their national governments working closely with the WHO and CDC continue to mount aggressive surveillance and public education measures. International assistance reportedly continues to flow to these countries to help bolster surveillance efforts.

A third strategy is enhancing the capacity of the three major African institutions - Africa Union (AU), the Africa Development Bank (ADB) and the UN Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) to provide leadership in Ebola response efforts. The recent joint launch of an Africa Ebola Fund by the AU, ADB and ECA to train and deploy African health workers to fight Ebola is a significant step in the right direction. The inclusion of Africa’s organized private sector in the conceptualization, launch and possible operation of the Ebola Fund is a masterstroke as the negative economic implications of the Ebola outbreak continues to become evident. The organized private sector in all parts of Africa represent one of the most important stakeholders in the fight against Ebola.

The fourth strategy is improve the fiscal, technical and logistic capacity of regional economic communities in the continent to provide support to member states. The reported plan by the Economic Community for West Africa (ECOWAS) to provide technical and logistics support to the three hardest hit countries is a welcome development. ECOWAS can mobilize the army medical corps of Nigeria, Senegal and Ghana with extensive expertise in disease response to assist the three hardest hit countries. Each region in Africa should have an Ebola Contingency Plan capable of mounting an aggressive, timely and effective response to new cases.

Fifth, Africans throughout the continent should benefit from scientifically based information, education and communication (IEC) campaign about the Ebola outbreak. Senegal and Nigeria already provide important templates on effective roll out of multimedia IEC campaigns targeting affected populations on risk factors of Ebola virus infection. These IEC campaigns may run counter to powerful native customs and practices regarding sickness behaviors and burials that may increase chances of transmitting the Ebola virus. In this regard, print and electronic media have very important role to play in reaching out to at-risk families and communities on how to maintain a high index of suspicion about Ebola and how best to avoid transmission.

Finally, African governments and institutions should assume the leadership role in organized efforts to rebuild health systems in the continent. The 2014 Ebola outbreak is a global wake- up call regarding serious deficiencies in health systems of the three hardest hit countries. Unfortunately, significant numbers of African countries currently Ebola-free have no better health systems. Sooner rather than later, Ebola or a similar fast spreading infectious disease will reach countries with grossly inadequate health systems with potentially, unimaginable consequences.

It is a race against time to contain and end the 2014 Ebola outbreak in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. It is even a much more difficult race against time to keep the rest of Africa Ebola-free in the increasingly global village of regular air, sea and land travels. A stitch in time saves lives. Time is of the essence.

By Dr. Chinua Akukwe

The author cakukwe@att.net is a National Academy Fellow and Chair, Africa Working Group, US Congress chartered National Academy of Public Administration, Washington, DC. He is a former Chair, Technical Advisory Board, Africa Center for Health and Human Security, George Washington University, Washington, DC.