China Foreign Minister's Visit to Kenya: An Analysis

|

|

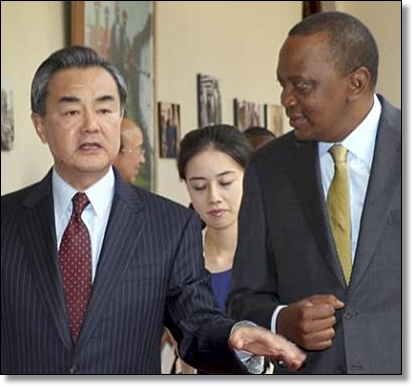

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi (left) with President Uhuru Kenyatta (Photo courtesy) |

The visit might have passed for a fairly innocuous and routine diplomatic event except that certain covert and overt factors make it special and worth analysis. Discerning Kenyans may ponder over why a visitor of the stature of foreign minister of the world’s second largest economy elected to visit their rather lowly-ranking-by-global-standards country so early in the year!

Well, symbolically, Wang’s visit was in keeping with a consistent tradition devised in 1991 whereby a high level Chinese official makes Africa his first destination every New Year. The significance of an Africa-first for a Chinese top official annually is often bundled with the calibration of Africa-China relations as founded on as such conceptions as south-south solidarity and true and sincere friendship. In this scheme of things, a Chinese top official would have elected to visit the country with which China operates the highest level of economic engagement: the United States of America. However, Chinese officials see relations with the US as a pursuit for explicitly pragmatic interests while relations with Africa are seen as those of natural allies in a competitive geopolitical environment.

The symbolism however tells only half the story as even the chummiest of international relations must be anchored in economic and political motivations. After all, until fairly recently, Kenya-China relations were cool rather than “tight” particularly during the Cold War epoch when the two nations travelled different ideological paths: the former gravitating West and capitalist; the latter decidedly communist.

Yet, since former President Jiang Zemin’s 1996 Africa tour in which Kenya was among the selected few, this East African country has remained high on China’s Africa agenda. It is worth noting that Jiang Zemin’s visit was momentous to the extent that it was it was the first ever visit by a Chinese president to Africa at the outset of China’s more robust policy toward Africa. Evidence of Kenya’s importance on the Chinese diplomatic circuit can be seen in the fact that the 2005 visit by former president Hu Jintao and last year’s visit by current Chinese premier Li Keqiang not mentioning other high ranking Chinese state and party officials over the years. The importance of these visits is that excepting South Africa, Tanzania, Nigeria, Ethiopia and Egypt, other African countries hardly attract the interest of Chinese leaders on such an elevated scale.

Indeed foreign minister Wang’s January visit resonates with historical as well as contemporary dynamics. In the present, media reporting on the visit indicates that one of his objectives was to lobby for the extradition of Chinese nationals facing charges in Kenya for allegedly being in Kenya illegally on a supposed criminal mission. This constitutes dicey headwinds in the hitherto even-keeled Kenya-China relations. Observers of this dramatic saga will be keenly watching to see how it develops given the mix of legal, nationalistic and diplomatic dimensions it has wended into. The elephant in the room for which perhaps only time will settle is: will the legal, nationalistic and diplomatic maneuvering on the matter on the Chinese and Kenyan side put paid to Kenya-China engagements?

Notwithstanding the cyber-crime conundrum, analysts might have missed other significant factors that might have impelled Wang to make the symbolic junket to Kenya. Probably the most crucial of these factors is Kenya’s geopolitical positioning on the continent. Not long after he was elected President, Uhuru Kenyatta famously encapsulated Kenya’s foreign policy as “Africa first, Africa second and Africa third.” He followed up this with highly visible visits to a number of African countries. Uhuru’s “Africa policy” was quickly conflated with his battle against the International Criminal Court (ICC) charges for crimes against human – now water under the bridge - in that he was seen as lobbying African leaders to do him a good turn vis a vis the ICC specifically and the West generally. On this score, China, the first non-African country for Uhuru to visit as president, is seen to have been a friend in deed. But more importantly, Chinese officials might have noted Kenya’s fallout with the West and its rising stature on the continent in such a manner to earmark it a higher ranking in its African policy. It is probable that Chinese foreign policy strategists might have seen Kenya as a robust African ally in the continuing battle with the West on myriad political and economic issues.

On the East African front, Uhuru and Kenya have been seen as the cog in the so-called coalition of the willing wheel bringing together Uganda, Rwanda and South Sudan and more tepidly Burundi. For instance it will be remembered that when Premier Li Keqiang visited Kenya May last year, one of the multilateral meetings he held was with presidents Yoweri Museveni, Salva Kiir and Paul Kagame with Uhuru playing host. This was in the context of discussions for the construction of East African railway system. Indeed unconfirmed sources indicated that, Kenya, Uganda and Rwanda had initially sought Chinese capital for the independent construction of their railways only for the Chinese side to advice for seamless cross-border infrastructure. Bundled with the near-incontestable Kenyan status as the regional economic powerhouse, all these make Kenya attractive as the gateway for Chinese economic and political interests in East Africa.

An equally powerful factor revolves around what several analysts refer to as “China’s long memory,” one in which Kenya is the few African countries with claim to bona fides. The fact of China leveraging history to the present can be seen in President Xi Jinping’s promulgation of the geopolitical policy-cum-strategy variously referred to as the “Silk Road Economic Belt,” “new Silk Road”, “Silk Road and Maritime Silk Road”, “Chinese and 21st-Century New Silk Road” and “Silk Road of the Sea” last year. At its very basic, the policy looks to see China expend resources on the revival of the ancient trade routes from southern China to Eurasia, Middle East, South Asia, South East Asia and Africa. To this end, the Chinese government unveiled a $40 billion Silk Road Fund, a demonstration if any was needed, that the Silk Road strategy sits at the heart of China’s global economic strategy.

In the Silk Road cartographic models that have been generated, Africa feature not by road extensions but by a maritime route that touches Mombasa on the East Africa coast (with a short dash to Nairobi) and then extends via the Red Sea to Egypt. In essence therefore the Kenyan coast is the landing point for China’s economic plans in the Sub Saharan region going forward. It is in these respects that Chinese interest in the ports on the Kenyan coast (Lamu and Mombasa) as well as the Mombasa-Nairobi railways – funded and constructed with Chinese loans – should be seen.

So why is Kenya being included in the New Silk Road strategy? The straightforward answer is that the Kenyan coast was the site of ancient voyages by Chinese maritime ships. Specifically, the famous Chinese admiral, Zheng He led the maritime armada of ships to Malindi and Lamu in 1418. Indeed, one of the symbolic Kenya-China cultural project that has been underway since 2010 is the $2.4 million archeological research undertaken as partnership between the National Museums of China and the National Museums of Kenya.

The upshot is that foreign minister Wang Yi might have made Nairobi his capital of choice for his maiden visit anywhere in the world in furtherance of the African dimensions of the Silk Road concept. Wang might have well elected to make his maiden tour of Africa elsewhere on the continent. After all, Kenya has hogged a little of Chinese visits than other African countries. Indeed Premier Li Keqiang was in Kenya less than a year ago. It would appear that the significance of the New Silk Road – in addition to Kenya’s econo-political positioning – were powerful motivations for the visit.

By Bob Wekesa

The author job.wekesa@wits.ac.za is a PhD candidate at Communication University of China and Research Associate at University of the Witwatersrand.