Mining Investment Fiasco in Zambia: Is the Law Crazy?

|

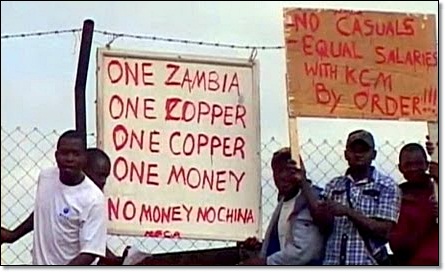

| Zambian miners protest Photo courtesy |

Therefore, if there is anyone to call stupid here, it’s the law….” Zambia operates under an economically liberalized framework. I agree with Labour Minister Fackson Shamenda, “Government has no business in business.” However, government has a role to play, albeit, a limited role, to ensuring that a right legal environment exists which sustains a level of fair competition. In Zambia’s case, it is competition between an investor against the other; between the investor and the mine worker; and between government and its bidding process.

Zambia relies very heavily on copper revenue. The country's economy is reliant on copper exports, which make up 80 percent of foreign earnings. To understand the ambit under which the mining sector has been managed in Zambia, it is important to delve into a brief history. I can compare the Zambia mining scenario to a beautiful woman who has been married to three different men.

First, she was under private hands during the colonial era anywhere from 1890 to 1964. Then she came under public ownership after independence up to 1990. And again she went back in the private hands during the liberalization of the economy from 1991. The best marriage was under the first modality owing to factors like the availability of copper under the ground, cheap African labour, a smaller population to satisfy and relatively good management of the copper proceeds. However, under the other two ownership modalities, the revenue accruing to the public purse declined. This has not been due to poor leadership as postulated by many, there have been factors. Chief among them is that copper outputs have been declining just as the price of copper has been fluctuating.

Of course, under the UNIP era, the mines were under a One Party State, and therefore, state owned, and necessarily it was not feasible to properly manage the mines without political interference. Generally, the copper output rose after the Great Depression between 1930 and 1974. Between 1975 and 1999, both copper prices and output plummeted although there has been a steady increase since 2011. The dream of the Chiluba era was that with liberalization of the copper industry revenues would soar, but mistakes were and continue to be made. Among these mistakes have been “tax policies that provided overly generous terms to companies as well as practices of transfer pricing.”

One thing is sure in a mono-economy depending entirely on one commodity like copper, namely that, there ought to be favourable marketing conditions, augmented by good output, to continue to perform. But there is only one thing that should be constant; a strong legislative regime that will ensure that, come rain or sunshine, the mechanics are in place to weather the fluctuating storm. And that scheme begins with the reformed Mines and Minerals Development Act, 2008 [No. 7 of 2008] (the “Act”). This Act replaced the 1995 Mines and Minerals Act, and was passed to “reform the fiscal regime and capture a greater share of the [copper] revenues.”

Thus, under s. 133 of the Act mineral royalties are prescribed between three and five per centum of norm value or gross value of base, precious, energy or gemstone minerals produced under the licence. Suffice to mention, too, that this Act has obliterated the so-called “stabilization clause” which in the previous law had bound the Government of Zambia to alter neither the magnitude nor the structure of any of the incentive provided to the investor. Moreover, this clause did forbid government from taking any “legislation or…administrative measures or decree or…any other action or omission whatsoever” to rectify a problem or offset a crisis even if it was against the very wellbeing of the nation. Again, the investor won.

The new Act has not diminished the power of the president in the enforcement of mineral rights in Zambia. Section 3 empowers the president with “All rights of ownership in, searching for, mining and rights to disposing of, minerals whosesoever located in the Republic,” and by extension, he remains the main controller of mineral interests through the Director-General, Minister of Lands and Minister of Finance. The latter is preeminent usually because of the taxation component.

Thus, what the president did recently, whereby he promised to “temporarily take over viable mines whose owners feel it is economically challenging to operate in Zambia” whilst waiting for another serious mining investor to come and operate, was in tandem with the new legislative mandate. Two of Zambia’s largest mining investors, Konkola Copper Mines and Mopani Copper Mines, are laying off or rather retrenching 2,503 contract employees and 5,331 workers, respectively. The other problem buffeting Zambia like a disobedient hurricane is the manner in which investing companies subject the Zambian labour force to slavery conditions. Under the new legislation government has no permanent solution, such as taking over of the troublesome mining companies, but the end in mind should be at the beginning.

While government should not parent the industry, it has an obligation to ensure that more serious and well-vetted mining investing companies are selected. This should be done right at the point of bidding, not as a response to a major strike or laying off of mining workers. As the president has hinted, it is in the best interest of Zambia for government to assume temporary possession of the mines whose owners have neglected. Zambia should look for a serious investor or investors. This is a right move.

The fears that bad reporting about a country by the Post scares away investors as promulgated by Kambwili, Information Minister under the PF, are not sustainable. Copper demands continue to rise. Zambia is the eighth largest producer of copper in the world (bettered only by Chile, China, Peru, USA, DRC, Australia, and Russia). But Zambia is the only country among the ten (10) top copper-producing countries that recorded a drop in production from 2013 to 2014. In 2013, Zambia produced 760,000 tonnes of copper, but only 730,000 tonnes in 2014. The reason is simple: Zambia had decided to increase royalties from six (6) percent to 20 percent for open-pit mining operations. Some investors like First Quantum and Glencore reacted by holding off their expansion quest.

What Zambia is doing now is in order. Each nation has a vision of economic growth. Zambia should not be an exception. In fact, if Zambia adheres to the current policy, among other things of tenaciously implementing the Act and increasing the royalties to at least 20 percent, from “2013 to 2025, on average, five (5) percent to seven (7) percent of GDP can be raised from mining operations.” Because and otherwise, “The people of Zambia have still not reached the average income level that they had in 1980.” For the past dozen years, Zambia has allowed investors to dictate the pace of development. But only a few Kwachas have fallen into people’s pockets. A seven percent of GDP raise could be the critical link to accelerating the country’s development process. It could be sufficient to finance activities needed to stabilize the economy, meet health targets, and alleviate the pangs of poverty.

To end with Joseph Mwenda’s sensibility, no, the law is not stupid. And the analogy of a marriage relationship may not hold in the case of Zambia. In Zambia, 10,000 workers still do not have necessary employment protections and are underpaid, in addition to, suffering from various abuses. Therefore, they have a point when they rise to strike. The law in its current form on mining in Zambia is good; but it must be implemented without fear or favouritism. Government has to decide between being tough and improve its people’s lives and being ingratiated and only help some investors get richer at the expense of the people of Zambia. And at this stage, Zambia Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU) and government cannot afford to fight from the opposite ends; they both should fight to protect the plight of the workers without sacrificing potential relationships with credible and tested investors in Zambia’s lucrative mining industry. The said implemented, the future economic outlook of Zambia can only be brighter!

By Charles Mwewa

Author of "Zambia: Struggles of My People" and various other books on Zambia. Visit Charles' blog: http://www.mwewa.ca/