A Call to Renew, Reimagine and Rebuild

We meet in extraordinary times. Never in our history have we met in Synod during a pandemic, and very rarely have the lives of our parishes and Diocese been as topsy-turvy as in the last 18 months.

Apart from the pandemic, when it comes to the question of sharing the dividends of our democracy fairly among all, the chickens have truly come home to roost. The looting and the burning we saw mainly in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng may have been set off by developments around our former president, but the speed at which the mayhem spread spoke to the ills and the toxicity of our divided society. I will return to this subject in a few minutes.

Perhaps it has only been in times of war that our lives have been turned upside down in the way they have since the coronavirus struck early last year. As I began writing this Charge, soon after Level 3 was imposed and before the events of recent weeks, I have to confess to you that I felt trapped in the heaviness of now, battling to find a ray of light at the end of a tunnel.

A special mention tonight for victims and survivors of the pandemic: we pray for those who are grieving or suffering as a result of death, losing relatives and friends, and for those who have lost their jobs or had their wages cut. I know you will join me in sending heartfelt condolences to the lay and clergy families of those in the Diocese who have died. In the wider church in Africa, we extend condolences to the family of our beloved Bishop Ellinah Wamukoya of Swaziland, who died at the beginning of the pandemic, and to sister Provinces in Africa who have lost bishops to Covid-19.

The 18th century Irish philosopher, Edmund Burke, wrote of another epoch that “an event has happened upon which it is difficult to speak and impossible to be silent.” The same can be said of the events of the past year-and-a-half. Even before the recent violence, it has been a time of “multiple pandemics”: of Covid-19 with its inhumane losses and its legacy of grinding poverty with job losses, food insecurity and social fragmentation; of horrific violence, including a sharp rise in the scandal of gender-based violence and violence against children; and an era in which naked, unmasked racism has re-emerged in all its evil manifestations, in many parts of the world.

Even in the midst of so much suffering during the pandemic, unscrupulous people have profited from it. We have seen unmitigated corruption and looting from the public purse; corruption which amounts to theft from those who are most vulnerable; looting which has so damaged the credibility of politicians that last week’s appeals to the “have-nots” to stop looting from the “haves” were but a cruel joke. These are things, to use Burke’s language, of which, because of their depravity and gravity, it is difficult to speak and yet, things about which we dare not be silent.

What would our ancestors in faith and struggle have said about these times? What insights would they have offered? I have often recalled the hermeneutic offered by Steve Biko, who our church commemorates on the 12th of September. The Collect we have adopted for that commemoration reads:

Lord of the Cross, you taught us

in the life of your servant Bantu Stephen Biko

that it was better to die for an idea that shall live

than to live for an idea that will die:

grant us the faith to take up our Cross daily

and to follow Christ ;

who is alive and reigns with you and the Holy

Spirit, one God now and ever.

In the spirit of Steve Biko, let us take up our Crosses daily, and mobilise together across barriers in society to fight the evils we have experienced during the pandemic and the greed which is destabilizing our society. Let us emulate the courage of those, in South Africa, in the United States and elsewhere, who have taken up the struggle for recognition that Black Lives Do Matter and that we need to build a society and an economy in which that is fully reflected.

As leaders and followers, we need to reflect deeply on what our country has become. We cannot go on as we are. We need to re-set our compasses and choose a different direction. In the spirit of Paul writing to the Corinthians (1 Cor 9:16), we are under a burden and a demand to preach into what is happening, an obligation to preach a Gospel of peace with justice – and woe betide us if we do not speak.

Those wedded to a capitalist model have to acknowledge that our current financial and economic systems are not serving the common good; they are creating joblessness and inequality, to the extent that unemployment is running at 32.6 percent, youth unemployment is 46.3 percent, and the World Bank says we are the most unequal country on earth. We have to recommit to closing the gap between the excessively rich and the debilitatingly poor.

We commemorate Mary Magdalene, “the apostle to the apostles”. Her witness offers us important insights in these times when all of us are challenged by our various pandemics, whether of the virus named Covid-19, or of violence perpetrated on women, children and the victims of gang warfare in too many of our communities, or of the violence of poverty and dispossession.

Note how Mary Magdalene and her companions are there at the place of the Crucifixion and at the empty tomb, determined and resolute. In contemporary terms, they are the women in our communities who gather around the bodies of young people brutally killed in gang warfare, or who bury young girls who have been molested, raped and murdered. By not leaving – indeed, we are told that “they stand” – they display resilience, not weakening under the weight of what goes on around them. They won't be silenced, and their resilience becomes something shared, allowing them to face an uncertain future together. They challenge us likewise to remain resilient, to refuse to overlook the pain of our current conditions, the poverty and the widening gaps in income and the stares of hungry children.

Their witness offers us the rays of hope and light I was looking for when I started this Charge. So do the words of the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams. He points out that by casting doubt on what he calls “the assumption of guaranteed security” that the prosperous in our world have enjoyed for decades, the pandemic brings home to us that we are always “in a situation of shared failure and shared insecurity”. The hope is to be found when we recognise this shared reality, and take the opportunity to open our hearts to one another.

Faith, says Rowan Williams, “invites us to confront our shared fragility with honesty and compassion, recognising our need of one another, our need for the neighbour to be well and safe — instead of falling back on our fearful attempts to be safe at the neighbour’s expense.” Ends quote. If only the G7 countries, and others in the Global North, would hear this, end their vaccine nationalism, and move speedily to help the rest of the world get vaccinated at the same rate in every country. For our part, those of us in the Global South must stand, raise our voices, share our skills, strategise with others and keep vigil until those who have power in the private and the public sectors make good on their early Covid-19 commitments.

It is not only in the international domain we need to act, it is also right here at home, here where our much-lauded Constitution guarantees the right of access to basic health care. Yet those who have access to technology to sign up for vaccines are at an advantage. Those with money, access and private health care have an advantage over those with very little or none. In a time of national crisis, people without voices or resources remain invisible or only partially visible.

In an ongoing or post-Covid world, we need to think and pray about what a new kind of missionary focus, one that intuitively reaches out to encounter and engage with others, would look like. I was interested to hear recently of something that Nicky Gumbel is reported to have said: that when the fearful run away from an encounter with suffering and sickness, Christians run towards it – and it makes a great difference to church growth. But it is not only in the realms of physical health and church growth that we need what I think of as a new missionary praxis – we need it as a way of facing up to all of our society's social pathologies.

In our own Diocese, the patterns of ongoing privilege and exclusion which I spoke about a moment ago at a national level still bite deeply in Cape Town, for example when it comes to the continuation of apartheid spatial planning. The poor and people of colour who depend on public housing continue to be shifted to the outskirts of cities, to dormitory suburbs, far from places of work. Voices are thankfully being raised now for the release of vacant sites, to release national land and re-purpose buildings so that we can move towards that most basic of human rights, the right to shelter. As churches we need to find ways of leveraging power to shift the needle.

The challenge may be daunting, but we need to replicate Steve Biko's emphasis on jointly seeking composite answers and creating communities of sisters and brothers. Now is a time when the pandemic – and the last week’s events – have brought new perspectives to old fissures, exposed new wounds and highlighted unresolved tensions. In the light of these signs of the times, we have to engage again, and with an even greater urgency.

We must not forget, as we set about these critical ministries, that the Church has its own legacies of compromise and complicity with the wrongs of the past. Our words, our resolutions of opposition to apartheid, to exploitation and to the injustices that have shaped our culture do not absolve us or wipe away the ongoing systemic consequences of those involvements and benefits. They will continue to undermine trust and attempts at reconciliation. Yet we cannot forego the slow task of building a more solid foundation for the future. Our churches have the reach and the inner resources to continue to be places of healing, reconciliation and hope.

In this year of Archbishop Tutu’s 90th birthday, and the 60th anniversary of his consecration as a priest, we turn to his wisdom. “Forgiving and being reconciled to our enemies or to our loved ones,” he says “are not about pretending that things are other than they are. It is not about patting one another on the back and turning a blind eye to the wrong. True reconciliation exposes the awfulness, the abuse, the hurt, the truth.”

Early on in the pandemic, the great Indian novelist Arundhati Roy posed the question: “What lies ahead?” She answered, “Re-imagining the world. Only that.” Christians, with our unique spiritual gifts, with compassion written into our very DNA, must, as part of our missionary impetus, ask the same question and bring our anointing into shaping the future.

As God's people in the Diocese of Cape Town, we need a new missionary praxis, one in which we examine anew the relevance of all our practices and structures with a view to moving from maintenance to mission. We must live out our conviction that, indeed, our Redeemer lives! Rooted in that certainty, we must – we can – renew, re-imagine and rebuild. We can bring about fairness, equity, generosity, sharing and caring for the environment. We can both realise and share the dividends of our democracy. May we have the courage to continue our journey until, in the words of Chief Albert Luthuli, we will have built “a home for all.” May God hasten that day.

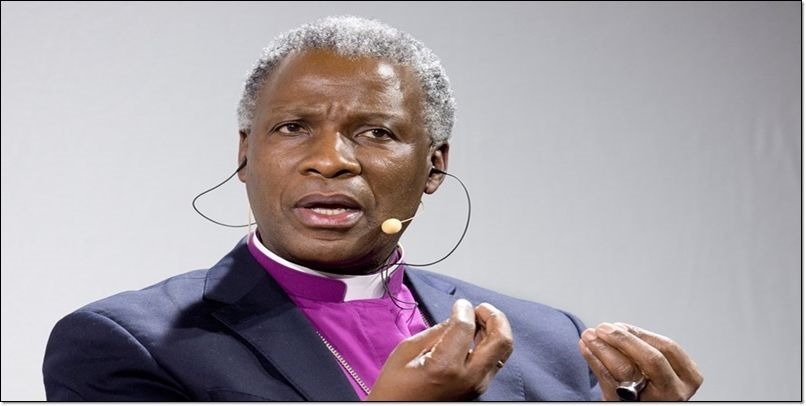

By The Most Revd Dr Thabo Makgoba

Anglica Archbishop of Cape Town