Global Campaign to Decriminalise Poverty & Status

The law treats the rich very differently to the poor. The criminal justice system, as a whole, responds differently to the haves than to the have-nots. That is the reality.

The rich and the more privileged have access to better resources, they can afford legal representation, they can afford to pay bail, they can afford to pay fines. The rich and the affluent are not locked up for petty offences. The poor are much more likely to experience unlawful and excessive arrest and detention and disproportionate sentencing. They are, by and large, the ones in overcrowded prisons.

It boils down to a very simple and straightforward question, who is more likely to suffer violations and infringements of their human rights - the rich or the poor?

Who has the resources to more successfully enforce their human rights – the rich or the poor?

This raises the fundamental question of how do we use the law and for whose benefit? We very frequently refer to the rule of law, meaning the principle of governance in which all persons, institutions and entities, in both the public and private sphere, are accountable in terms of laws that are, firstly, publicly promulgated, secondly, equally enforced, and, thirdly, independently adjudicated. But is that really how the law works? Are we all equal before the law? The honest answer is no.

There is sometimes an extremely thin line between using law enforcement for purposes of safety, as opposed to using it for the purposes of protecting wealth, status, power or privilege. It would be naïve to deny that throughout the history of the world the law has, in some instances, been used in a way that prejudices the poor, whilst protecting the rich, the establishment or those in power. We can often trace or link the criminalisation of certain offences by way of our history. Many offences which are criminalised today are the result of colonialism and/or legislating for morality. Here we think of laws such as those relating to criminalising LGBTIQ practices and laws criminalising sex work.

And we still live with the consequences today. For example, a report released recently by ILGA World states that as at the end of 2020, some 69 UN member States continue to criminalise same-sex consensual activity. At least 34 UN member States have actively enforced such criminalising laws over the past five years, but the number is possibly much higher.

But it is often in municipal bylaws, at local government or municipal level, where one sees the biggest remnants of colonialism. Various countries, especially those which were British colonies still have by-laws originating from or based on the UK’s common law offence of “public nuisance” – it is generally considered as an unlawful act or omission which interferes with the lives, comfort or property of the general public.

England’s Vagrancy Act of 1824 makes it a criminal offence to sleep rough or to beg. Last month, it was announced that the UK is currently – nearly 100 years after the passing said law – reviewing the Vagrancy Act.

In the accompanying factsheet it is said that the UK Government is committed to ending rough sleeping and that no one should be criminalised simply for having nowhere to live and thus there is a commitment to repeal this outdated Act. But, it also states that “we must balance our role in providing essential support for the vulnerable with ensuring that we do not weaken the ability of police to protect communities.”

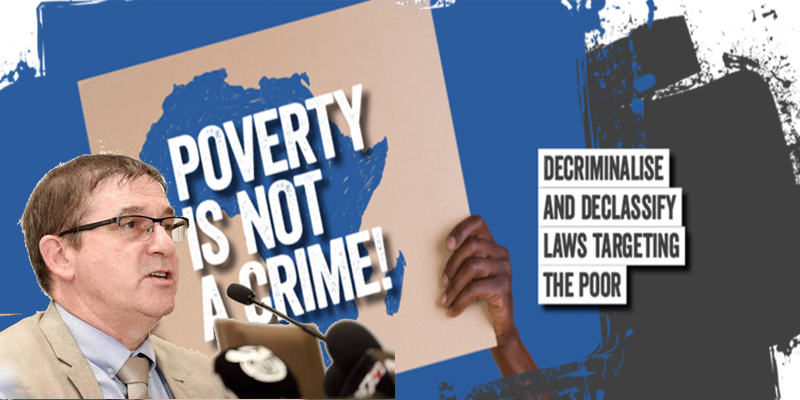

In South Africa, on World Homeless Day, various institutions such as the Africa Criminal Justice Reform of University of the Western Cape), the African Policing Civilian Oversight Forum, the Centre for Human Rights of the University of Pretoria, Lawyers for Human Rights and others marked the official launch of a civil society campaign to decriminalise poverty-related by-laws in South Africa, thus rejecting the effective criminalisation of poverty through municipal by- laws currently targeting the poor and the most marginalised in South Africa.

We have various by-laws criminalising or penalising conduct related to the performance of life-sustaining activities in public spaces. Examples include the prohibiting persons from loitering or sleeping in public spaces; the solicitation of a vehicle driver for the purpose of guarding the vehicle; pushing a trolley on a highway, begging, or washing in a public bathroom. Such by-laws indirectly discriminate against some of the most marginalised people in our society.

Laws can also be used to stifle dissent or association, rather than for the purposes of public safety. This is something we know every well from our colonial and apartheid past.

When a law appears to be neutral, but impacts different people in different ways - not only rich versus poor, but also along the lines of race, sex, gender, ethnicity or if it targets people based on their social, political and economic status – it creates power imbalance or unequal power relation which then becomes more and more entrenched over time.

This is something are courts have realised – for example, in 2019 South Africa’s Supreme Court of Appeal delivered a ruling on the removal of property of persons who were homeless. The applicants were deprived of their property during a clean-up exercise by the municipality. The Court held that the destruction of the applicants’ property was unconstitutional and unlawful.

There are various instruments which could assist in reducing the criminalization of poverty in a number of different ways.

In the context of Africa specifically, there is the Kampala Declaration’s Plan of Action to review penal policies and reconsider the use of prisons to prevent crime, while the Ouagadougou Declaration and Plan of Action on Accelerating Prisons and Penal Reforms in Africa accordingly recommended the decriminalisation of some offences such as being rogue and vagabond, loitering, prostitution, failure to pay debts and disobedience to parents.

The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights’ Principles on the Decriminalisation of Petty Offences notes that petty offences are inconsistent with the right to dignity and freedom from ill-treatment on the basis that their enforcement contributes to overcrowding in places of detention or imprisonment.

In addition, many of you will be familiar with discussions on the creation of a Model Law for Police in Africa.

The Model Law includes provisions on the requirement for police to use alternatives to arrest for petty offences, and aims to codify the requirements of the Principles on the Decriminalisation of Petty Offences in Africa.

We must seriously address the issue of the decriminalization of poverty, all the more so because we are simply not winning the war against poverty and inequality.

In fact, the United Nations’ latest statistics tell us that the COVID-19 pandemic has put steady progress in poverty reduction over the past 25 years into reverse, with the number of people in extreme poverty increasing for the first time in a generation.

Rising inflation and the impacts of the war in Ukraine may, according to the UN’s research, derail progress further.

The combined crises could lead to an additional 75 million to 95 million people living in extreme poverty in 2022, compared with pre-pandemic projections.

While almost all countries have introduced new social protection measures in response to the crisis, many were short-term in nature, and large numbers of vulnerable people have not yet benefited from them.

According to the UN, and I quote – “As things stand, the world is not on track to end poverty by 2030, with poorer countries now needing unprecedented levels of pro-poor growth to achieve this goal.…

Forecasts for 2022 estimate that 75 million more people than expected prior to the pandemic will be living in extreme poverty. Rising food prices and the broader impacts of the war in Ukraine could push that number even higher, to 95 million, leaving the world even further from meeting the target of ending extreme poverty by 2030.”

So how do we break this cycle of criminalizing poverty?

Firstly, we need legislative reform. Here in South Africa, we are still busy repealing old apartheid legislation. By way of example, we’ve recently published for comment the new Unlawful Entry on Premises Bill to repeal and replace our old Trespass Act of 1959. Needless to say, the reaction from the public was rather polarizing, as you can imagine.

But before undertaking any legislative reform, we need to determine whether the law is impacting different people differently. Here in South Africa we are currently preparing a bill to decriminalize sex work.

And we know it will be contentious. But we know that it’s the sex workers who are currently suffering by way of being fined or being harassed by police, whilst their clients and the pimps do not face the same treatment.

Secondly, we need to think about the purpose of the law and what the impact of the law is. Are there not perhaps other more socially responsible and socially appropriate ways of dealing with an issue, e.g. in the case of petty offences, using detention as a last resort.

We should be paying more attention to prevention and harm reduction responses, such as the establishment of shelters, rather than responding primarily in punitive ways.

Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, we need to change societal attitudes. Being poor is not a crime. I’m often astounded at some of the comments posted on street or neighbourhood security WhatsApp groups, such as “suspicious-looking person in street”. When one goes out and looks, it’s a homeless person or someone begging. And being homeless should not automatically equate to “suspicious” or “dangerous”.

I want to wish you all the best for a very successful event. If we truly want to create a caring society, based on fundamental freedoms and human rights, we have to look at our criminal law responses.

There are often alternatives which are preventative and proactive, rather than reactive and have better outcomes for society as a whole.

By the Hon JH Jeffery, MP

Deputy Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development SA.