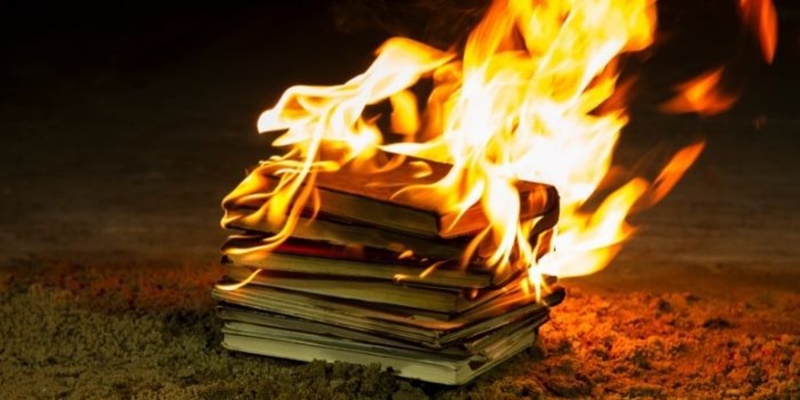

On the Burning of Schoolbooks after Examinations

Students of the examination class of Forest View Academy in Nairobi lit a fire to burn their

books after the class eight national examinations. One girl fell into the fire. She received first degree burns on the face and arms and was sent to the hospital for care. If it were not for the girl getting injured, the issue would not have been brought to the limelight.

The burning of books after examinations is not uncommon in Kenya. It is a habit, however, that needs deep interrogation. Why would students not want to preserve their books as reminders of their primary and secondary schooldays? What does it say about education if students are burning their books?

There are many reasons why pupils would want to destroy their books after examinations. First, there is a perception that schooling is a punishment. Students spend many hours sitting down listening to teachers and reading books. They consider classroom instruction boring and a waste of precious time that they could have spent playing games and relaxing.

Second, there is perception that examinations represent the end of education. Many people do not regard education as a continuous learning experience. They consider examinations as the end to a boring and tiring process that took them years to complete. The students celebrate by lighting bonfires and dancing around them. This end marks the beginning of a stage in life characterized by uncertainties.

A third reason students burn books is because they do not see the immediate gains from the process of education. The question of the relevance of Kenyan education has been an issue of major concern. Education was tailored to lead to employment in government and companies.

Students worked hard to compete for the available positions in government and the corporate world. Those who performed well in national examinations were assured employment in those entities. However, in the 1980s, structural adjustment programs initiated by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund were introduced in Kenya because the Kenyan government was not able to repay loans and was struggling to meet budgetary obligations.

There was need to overhaul the structure of the economy by introducing competitive market policies, cost sharing, retrenchments and the liberalization of trade and foreign exchange. The policies had adverse effects on the economy. Jobs were lost and employment in government and companies was frozen. The sharing of the cost of education between governments and families – or cost sharing – made education expensive and unavailable to most people. The implications for access to education were adverse. Graduates from all levels of education started competing for the few available jobs. Most graduates were left jobless. Cutthroat competition became part of the education system. Doing well in school and passing exams became the pathway to obtaining a good job.

To cope, academies and boarding schools were introduced. This meant being in school for long hours and cramming for examinations. Active learning in classrooms was abandoned and replaced with rote learning and preparation for examinations.

Storybooks and well written textbooks with detailed subject matter were replaced with technical books, including ones with tips on how to pass examinations. Learning became a process of memorization of facts which would later be regurgitated during examinations.

The impact on students of these changes in education was overwhelming. Students would spend many hours a week in classrooms and schools. They would wake up early

and leave late from school. They would even go to school on Saturdays. They had no time to be children. This killed the love of education and introduced a hatred of books. Students regarded learning as a punishment, which had to be endured rather than enjoyed. Students labored to read books rather than enjoying reading a good book. Books became their enemies. Writers and publishers,

instead of being creative and using the magic of words and language to entice students to read, wrote boring books that were tedious to read. This did not stimulate or motivate students to read. Reading in homes was also limited. Students were burdened with lots of homework, which was about reproducing the facts they had learned in school. Parents were busy. They were juggling with work to make ends meet to cope with the high costs of living. They had limited time to concentrate on their children’s learning activities.

Those who could afford it preferred to take their children to boarding schools, where teachers could take charge of supervising their children. In some boarding schools, children experienced a lot of stress. Many began to loath education. Their creative and innovative spirits were dulled, and schooling ceased to be an enjoyable experience.

Unemployed graduates became a negative motivator to those in school. Why pursue an education while the daughter or son of so and so, who is a university graduate, is at home with no job? The get-rich-quick culture, in which it did not matter how or where one obtained money, was also a negative incentive for learners. “The daughter or son of so and so has a lot of money but does not have much education, so why should I stay in school?”

Bombarded with all these negative incentives, students end up celebrating the end of education by burning books. “At last freedom has come.” For change to occur, we need to come up with policies for an inclusive and sustainable economy in which graduates do not have to compete for a few jobs. We need to put African history and culture and the joy of learning back into education. And our leaders need to show the value of and invest in education and teachers.

By Mary Njeri Kinyanjui

Activist Scholar in Residence, Buchanan Initiative for Peace and Nonviolence, Avila University, Kansas City, Missouri, USA, marykinyanjui@yahoo.com