The Flood Crisis in Kenya: A Wanton Disregard for Geospatial Expertise?

Based on Systems Thinking, we understand that: perceptions lag reality, working from whole to part is king, and dividing an elephant in half does not produce two small elephants.

The fragmented way in which decision-makers have been handling the cyclic crises of floods and subsequent droughts in Kenya betrays a chronic disregard for geospatial expertise and scientists.

Why Geospatial?

Geospatial expertise is key to anticipating, organising, perceiving, and interpreting location-based events, trends and patterns over time on Earth. In other words, the actionable location-based intelligence and shared visual evidence obtained from the surveying, Earth observation (EO) and geospatial mapping products and services aid in risk modelling, hence paving the way to reducing uncertainty into quantifiable risks. The resulting information is crucial for informing timely and effective derisking mechanisms. Deformation monitoring, a critical aspect of engineering surveys, must be practised routinely to forestall the common floodgates of disaster experienced during heavy rains, collapsing dams and buildings being ready examples.

The preceding statements lay a robust foundation for the lucid argumentation asserting that there has been a wanton disregard for geospatial expertise and scientists in the disaster governance model that has become normal practice in Kenya. Though not pre-empting in any way what the Institution of Surveyors of Kenya (ISK) is likely to champion during the upcoming tirades, if not constructive dialogues, on the flood crisis, this special issue is bold and assertive on the need for a culture change to tap into geospatial skills for enhanced disaster governance.

A Decision Crisis

Decision Science is critical in the face of the flood crisis Kenya is grappling with as the heavy downpours rage relentlessly. Though the two protagonists of Decision Science, Daniel Kahneman and Jay Forrester, have exited this earthly scene, their key contribution to this field lives on. The skewed behaviour of humans expressed in underestimating likely outcomes and overestimating the less likely events has been well observed and documented. In System Dynamics, we understand that perceptions lag reality, working from whole to part is king, and dividing an elephant in half does not produce two small elephants.

The fragmented way in which decision-makers have been handling the crises of floods and subsequent droughts in Kenya betrays a chronic disregard for expert advice. Roadside policy declarations not founded on data and science have only deepened the decision crisis. Long-term planning suffers as a result, exposing gaping holes in strategy and policy design. Yet, the gap is not prevalent because of a lack of decision support models, but because of a malevolent neglect of the available and suitable decision support tools and the expert champions of such.

Reactionary Rhythms in a Predictive Era?

The flooding crisis in Kenya and the sure drought crisis that will follow constitute a predictable cycle. In response, decision-makers have been swift to disregard early warning messages from experts, at a time when predictive models have been getting better and better with advances in geospatial data quality and geodata processing and modelling techniques and technologies. Disaster risk mitigation can only get better with predictive models, making it pathetic for a country to front reactionary responses, which are already far removed from preventive measures and light years behind the aspirational predictive measures that are becoming the rule in the era of Artificial Intelligence and Big Data.

Forgotten Disaster Governance Lessons

The COVID-19 pandemic bequeathed us lessons on disaster governance, which were documented in the book entitled The Future of Africa in the Post-COVID-19 World, co-authored by African scholars and published in 2021 by the Inter Region Economic Network (IREN) – a private think tank. Politicians are loud, watching as the number of flood victims in Kenya remains high and counting. Now, so evident is the ill-preparedness of government in all the 7Ts outlined as pillars of disaster governance in the book: Timing, Testing, Tracing, Transparency, Trust, Training, and Transdisciplinary Thinking (read more from page 5 of the book: The Future of Africa in the Post-COVID-19 World (April 2021). Inter Region Economic Network).

The Promise of Geospatial Modelling

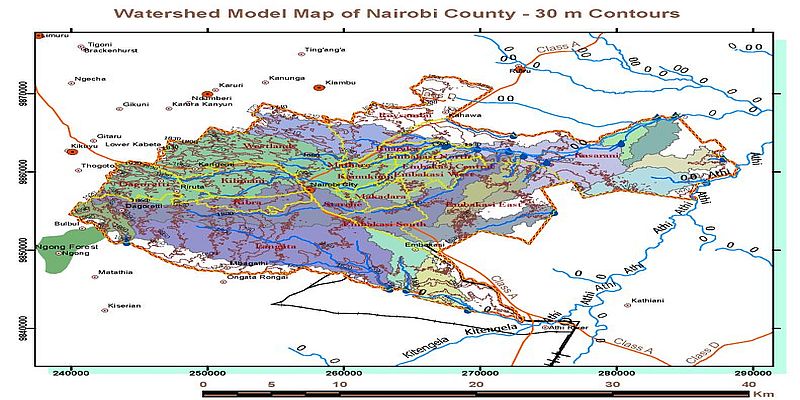

Quality decision-making against geohazards (e.g., floods, landslides, sinkholes, earthquakes, tsunamis, etc.) heavily depends on geospatial modelling and mapping with actionable visual evidence at scale. A scan of the flooding hotspots reveals a ready visual answer in geospatial modelling, with the map below displaying evident topographical predispositions by precise geolocation. Nowadays, unlike in the 1990s and earlier, we can readily extract such decision-support data and information from medium- to high-resolution satellite imagery and detailed geospatial surveying techniques e.g., terrestrial and airborne LiDAR/laser scanning and use of Unmanned/Uncrewed Aerial System Surveys to remotely collect key geodata and generate 3D models, including digital terrain models and even the more progressive products of extended reality such as Augmented Reality (AR), not to mention Digital Twins, all of which are key to modern and innovative facility and infrastructure management (Read more from this recommended reference practice-oriented book: Project Design for Geomatics Engineers and Surveyors, Second Edition: Amazon.co.uk: Ogaja, Clement, Adero, Nashon, Koome, Derrick: 9781032266794: Books)

Again, open geospatial data portals nowadays avail analysis-ready data (ARD) in support of disaster-mitigation models and Early Warning Systems (EWS) e.g., from SRTM (Shuttle Radar Topography Mission), Digital Earth Africa (DEA) and Esri Living Atlas.

Watershed modelling displays at scale, to all and sundry, how flow accumulation points are spread across space over time (see the map below). There is no shortage of Surveyors and GIS & Remote Sensing experts, who together provide the skills to share the evidence base to deal with floods through adequate spatial planning, complete with informed policy enforcement and compliance monitoring. Policy enforcement or lack of it due to corruption or otherwise, and the wanton disregard for professional guidance and advice, together expose the dearth of groomed culture and national values in Kenya.

Conclusion

While it may be said that the citizen behaviour of habitually ignoring various warnings against settling in riparian zones and other disaster hotspots is reprehensible, there is much more to disaster prevention than relying on the whims of citizens. This is where resolute action by governments, based on data models and science as advised by experts, finds its moral force and life-enhancing role. Therefore, to do justice to the demonstrated evidence of the half-hearted and lackadaisical manner in which Kenya has regarded experts in key decision support committees and the expert advice from scholars and professionals, it makes for a logical conclusion to apportion the larger share of the blame to the government’s ill-preparedness for, and weak and late response to, the flood crisis.

John Ngugi has successfully completed his BSc studies in Geoinformatics at Taita Taveta University (TTU), to graduate this year. Bonface Odhiambo has graduated from TTU with BSc in Geoinformatics and is working at LocateIT. Like many other students and graduates of TTU, they are among the youth mentees of Impact Borderless Digital (IBD) who benefit from the gap-filling youth talent and career mentorship sessions IBD regularly conducts outside the four walls of the classroom, which is a deliberate departure from the traditional linear brick and mortar approach to training. As a geospatial expert and Mentor under the FIG Mentoring Programme for Africa as well, the Founder of IBD (Nashon Adero) is passionate about mentoring the youth in geospatial skills and career development, besides other productivity and networking skills of the borderless and digital 21st-century workspace.