Insecurity Surges in the Sahel amid Anti-Imperialism Fervour

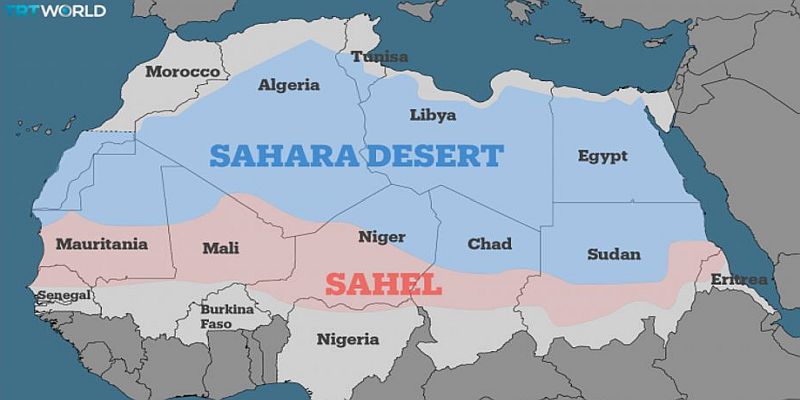

The Sahelian countries of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger triggered some excitement in several parts of Africa in the aftermath of military coups. Perhaps coups were not the ideal way to institutionalise power transfer. However, there were frustrations with the inability of civilian governments to decisively address insecurity in the region. Insecurity is the main cause of these coups in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. Burkina Faso had two coups in 2022; in January and September. Several coup attempts have also been reported over the last two years. Mali had three coups between 2012 and 2021. Niger’s military takeover occurred in July 2023.

Insecurity is worsening in these countries. Terrorist groups active in the region, including the Islamic State Sahel Province (previously Islamic State in the Greater Sahara), Jama'at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin, and others seem to be expanding their territorial reach. The fact that armed groups, including terrorists, are intensifying their activities highlights the failure of the military juntas to successfully combat them. These governments have noble intentions to fight insecurity but this remains a Herculean task given their limited resources among other factors.

The Fall of Gaddafi: An Accelerator of Insecurity in the Sahel

Muammar Gaddafi was a misunderstood personality. Perceptions about his so-called dictatorial and anti-West nature were shaped largely by Western propaganda. Ten years ago, I read Gaddafi’s “Green Book”, a brief text elaborating his political philosophy. Well, he was some intellectual of sorts. Obviously, his book is likely to be quickly dismissed for a propaganda instrument. Nonetheless, he explains the organisation and philosophy of his leadership.

In a world accustomed to Western standards of life, including political institutions, Gaddafi’s argument for popular conferences and people’s committees as better alternatives to modern-day parliaments kind of makes sense. It is drawn from the socio-political organisation of ancient societies. Rightly, traditional Africa, Arabic, and Asian societies chose rulers either through communal consensus or naturally via a kingship system. A host of Western societies also practiced such. But colonialism introduced and reinforced a system of governance that was contrarian to beliefs and practices of Africans and other nationalities in the Global South.

Anyway, NATO accomplished its long-held imperialistic dream of getting rid of Gaddafi, but this turned out to be another failed mission by Washington. Former President Barrack Obama has admitted his administration’s foreign policy failures in Libya. In hindsight, Gaddafi was arm-twisted by the US and its allies not to enrich Libya’s military-industrial complex. When the onslaught commenced, Gaddafi had no reliable warfare to counter NATO’s. He was exposed and relied on mercenaries from Mali, Niger, Chad, and Sudan. It is estimated 10,000 mercenaries were recruited by Gaddafi.

These mercenaries retreated to their backyards with Gaddafi’s ouster and death in 2011 sealing their fate financially. Their retreat implied a flow of weapons across the region. Don’t get it wrong; terrorist networks and armed groups existed in several parts of Africa prior to Gaddafi’s fall. However, Libya’s rupture and the movement of these groups exacerbated the threat of insurgency.

Mali was the first casualty following the 2012 Tuareg rebellion which resulted in a military coup in the same year. Tuaregs formed the largest contingent of mercenaries recruited by Gaddafi. The rebellion further evolved into widespread terrorism. Terrorists took advantage of the political situation to expand their operational reach. The situation also worsened in Burkina Faso from 2015 due to political instability.

Unpopular Foreign Military Interventions

The Sahel military regimes blame foreign military interventions, especially by France, for insecurity. This perhaps stems from French troops cooperating with some armed groups as a strategy to prevent the spread of insurgency, especially in Mali. France takes the blame for the political and economic exploitation of Francophone African states. Historically, France has masterminded coups, rigged elections, and sucked the economies of these countries. The anti-French stances adopted as the official foreign policy of these junta states have roots in the imperial French colonial past.

A critical issue to think about at this juncture is whether military interventions failed in the Sahel region or not. Partly, yes. Partly, no. Affirmatively, Operation Serval and Operation Barkhane, particularly the latter, were perceived as France’s occupation instead of interventions aimed at combating insurgencies. Commonsensically, Operation Barkhane would be expected to be successful after its eight-year presence. But terrorist groups gained more ground in this period across the region. At the same time, the UN peacekeeping mission in Mali (MINUSMA) failed to restore security in Mali despite its ten-year presence.

In the wake of the failures of these interventions, the governments of Sahel countries shift blame to France, MINUSMA, and other external entities. They are responsible for the deteriorating security in the region. This highlights why the region has become a coup belt. Nonetheless, the military-led governments are yet to improve the security situation having previously blamed civilian-led regimes for not aggressively combating armed groups. This illustrates that military governments are not solutions to weaknesses in statecraft.

Alternative Security Arrangements Not Promising

Security initiatives hatched by the Sahel states seem ineffective. While foreign military interventions failed to combat armed groups, local and regional-driven measures have not improved the security situation. For instance, the G5 Sahel Joint Force was unsuccessful in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. Fingers were pointed to France’s support of this joint force one of the reasons for its failure. However, none of these states want to take responsibility for persisting insecurity. Mali withdrew from the G5 in May 2022 and was later followed by Burkina Faso and Niger which exited in November 2023. These three states accused the joint force of failing to combat insurgents. But they did not assertively allocate enough resources towards the joint force. The military regimes and their supporters will quickly blame the civilian-led governments at that time but this is a lame argument since they have not improved the security situation. This issue will also cripple the operations of the joint force formed by the three countries under the Alliance of Sahel States.

The Sahel juntas anticipated strategic assistance from Russia through defense and security cooperation, which has increased over the last three years. Moscow has delivered more military equipment. Russia has organized strategic training and other capacity-building and development initiatives for the Sahel forces. Russian mercenaries have been deployed in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. Yet, the security situation remains precarious. The juntas perhaps anticipated the mercenaries to succeed as they did in the Central African Republic. However, they ignored the dynamics of these comparative security environments.

At the time of the deployment of the first contingent of Wagner mercenaries in Mali in December 2021, the Russo-Ukrainian war had not broken out. It is possible the situation could be different if there was no war. The Sahel states would be almost guaranteed near-unfettered access to the Russian military-industrial complex’s weapons and personnel. Who knows if Russian military personnel would be deployed on Sahelian soil? Quite cagey though as Moscow prefers mercenaries to avoid reputational hazards associated with troop deployment and misconduct. Maybe huge armies of mercenaries could be deployed instead of Russian soldiers. But these mercenaries are on the frontlines in the war. Even in the long run, the mercenaries do not hold any magic bullet in helping the Sahel states combat armed groups.

The Economic Community of West Africa States (ECOWAS) is a lame institution with respect to addressing insecurity in the region. The formation of the Alliance of Sahel States illustrates slow progress or none in improving the security situation by the ECOWAS. ECOWAS loudly threatened military intervention against the military regime in Niger prior to Burkina Faso and Mali ratifying their exit from the West African regional bloc. These were tantrums at best given that ECOWAS has all along been spineless since insurgencies intensified over a decade ago. At this moment and in the long term, ECOWAS can at best cooperate with the Alliance of Sahel States against insecurity in the region. Such cooperation seems unlikely due to multiple interests and factors.

The African Union (AU) lacks ambition and purpose against armed conflict. The AU excels at formulating policy blueprints regarding the continent’s future. However, the AU lacks the intellectual, personnel, and financial commitment to implement these blueprints. The Agenda 2063 formulated in 2013 envisaged the silencing of guns across Africa by 2020. Five years after the deadline, armed conflicts are a norm across Africa. Apart from the insurgencies in the Sahel, wars persist in Sudan and eastern DRC. Terrorism is on an upward trajectory in Somalia, Cabo Delgado Province in Mozambique, and eastern DRC among other regions. Rebellions continue threatening Ethiopia’s unity. Libya’s instability and insecurity seem not to give sleepless nights to the AU’s hierarchy. The AU’s complacency is not shocking though. For a continental institution whose headquarters was built by China and whose members are unbothered to fully finance its operations, nothing much can be expected from it. The AU’s response to armed conflict and insecurity in the Sahel is poor.

Outlook

Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger are technically on their own to address insecurity. Their best shot at meaningful cooperation to enhance joint counter-insurgency operations is Russia. But Moscow is entangled in a war against Ukraine. The anti-French sentiments fundamentally echo anti-cooperation with Western countries. The US is unlikely to take the front seat to attempt to succeed where the French failed. The prospects are so low for Trump’s administration to meddle in additional armed conflicts in Africa. On February 11, the US Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth said Washington’s partners in Africa must take the lead on their security. China’s involvement in such conflicts is unthinkable. Turkiye could be tempted but it is currently best placed to be a supplier of military equipment for its emerging military-industrial complex.

Terrorism will persist in the Sahel. This implies that political instability will continue in the region. Additional coups and coup attempts are certain. The joint force by the Alliance of Sahel States is not a security nostrum. This effort must be backed up with broad, well-coordinated security operations by ECOWAS and the AU. It is important to note though that tackling insecurity in the Sahel should not be an isolated affair. Pursuing and restoring stability in Libya, Sudan, the Lake Chad region, the Horn, and other parts of Africa is critical for Sahel’s stability. Yet, African state and non-state agencies are not acting fast enough to stem the insecurity crisis in the Sahel. The region’s military governments are attempting to thrive on the anti-imperialism mantra. But time is catching up with them on this amorphous management of state affairs. They may not be competent enough to transform their countries.

The writer, Sitati Wasilwa, is a geopolitical and governance analyst.