Migrants Feel the Heat of Economic Crisis

Migrants are among the hardest-hit labour force groups in the current downturn. In most OECD countries, the unemployment rate of immigrants is increasing more rapidly than among natives. In the United States, for example, the unemployment rate of immigrants was below that of the native-born prior to the crisis, it is now above (10% for immigrants compared to 9% for natives as of March 2009). In Spain, more than one out of four immigrants in the labour force is now unemployed (March 2009), a proportion which rises to more than two out of five for immigrants from Africa.

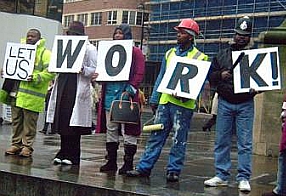

|

| Migrants demand for jobs Photo courtesy |

Many of the countries which are hardest hit were also among those which had record-high migration inflows in the years prior to the crisis, such as Ireland, the United Kingdom and Spain. This is a worrying coincidence. We know from past crises that arriving just before or during a severe economic downturn can have a lasting negative impact on the labour market outcomes of immigrants. In these challenging times, policymakers should address labour market integration of immigrants as a matter of priority.

Not long ago, many OECD countries were looking to labour migration as one way to address labour shortages and the expected impact of ageing. At the same time, inflows of both permanent and temporary labour migrants increased in many European countries and in the traditional settlement countries of Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States.

The International Migration Outlook shows the first evidence that the economic downturn has put a brake on this rising trend in labour migration. In the United Kingdom and Ireland, for example, migration flows from the new EU member countries have declined by more than half.

Countries are also reducing their labour migration programmes. Italy has announced its intention to set its quota for non-seasonal labour migration to zero this year, compared with 150 000 in 2008. Korea has more than halved its quota for temporary foreign workers under bilateral schemes. Australia has reduced its programme of permanent labour migrants by setting a quota 20% below the initially planned target for the ongoing fiscal year.

Ageing, technological change, and the integration of the world economy were among the driving forces of the accelleration of labour migration prior to the crisis. They will resurface with recovery. And not all labour shortages disappear during a downturn, nor does humanitarian or familiy migration come to a halt. Migration is not a tap that can be turned on and off at will.

We need a migration policy that is responsive to short-term economic conditions without denying the more structural needs. A system that seeks to ensure better lives for immigrants and their children while reducing irregular migration and illegal employment by redirecting them into legal channels needs to account for three basic insights:

*First, labour needs can manifest themselves at all skill levels. Failure to acknowledge this, notably regarding needs for low-skilled labour, has often contributed to a climate favourable to irregular migration.

*Second, many future labour needs will be of a long-term nature. It is therefore illusory to believe that such needs can be filled through temporary migration alone.

*Third, a successful labour migration policy involves a greater role for employers in identifying and selecting immigrants. Sound migration management thus needs to incorporate incentives for both employers and immigrants to follow the rules, as well as safeguards to protect immigrant and domestic workers from exploitation.

We need fair and effective migration and integration policies – policies that work and adjust to both good economic times and bad ones. This also means that OECD governments should strengthen their co-operation with developing countries. The most recent available estimates show that the crisis has had a major impact on remittance flows to origin countries. The World Bank forecasts a decrease in remittances of between 5 and 8 per cent in 2009 from USD 305 billion in 2008. The situation should be monitored closely as remittances contribute to poverty reduction and play an important role in supporting household spending on education and health in developing countries. Greater effort should be made to decrease the costs of remitting money. We also need to ensure that the benefits of migration are shared between sending and receiving countries. This requires responsible recruitment policies to avoid the risk of brain drain and greater portability of social rights to reduce obstacles to returns.

Finally, special attention should be paid to a balanced public discourse on immigration. It is important to refrain from a rhetoric that can accommodate if not reinforce discriminatory attitudes against migrants, and may lead to migrants’ disaffection with the host-country society.

We should aim for a world in which immigrants and their offspring are well integrated in the labour market, a world in which the potential benefits from international migration are reaped, to the advantage of all stakeholders involved. This can be achieved with the right policies. Now is the time to implement them.

By Angel Gurría,

OECD Secretary-General