The Crimes of Bongo

Apartheid & Terror in Africa's Gardens of Eden

By Keith Harmon Snow

13 July 2009

Keith Harmon Snow is the 2009 Regent's Lecturer in Law & Society at the

The June death of Gabon’s little ‘Big Man’—President Al Hajji Omar Bongo Ondimba—inspired praise worldwide.

Cameroon’s President Biya saluted Bongo’s wisdom while French President Sarkozy called Bongo the “great and loyal friend of France.” Equatorial Guinea declared three days of national mourning and a ‘saddened’ U.S. President Obama lauded Bongo’s role in ‘shaping’ U.S.-Gabon relations for 41 years and his dedication to nature conservation and conflict resolution. “At a continental level,” bemoaned Zambia’s President Banda, “he was a pan-Africanist who tirelessly and tenaciously worked for the unity of the African continent.”

|

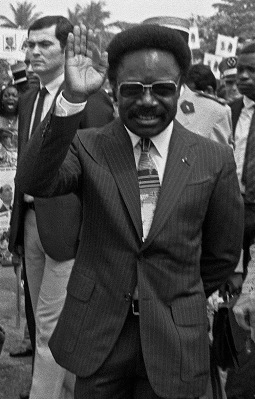

| The late Omar Bongo in 1965 |

Note the white secret service agent in the background in this ancient photo of Gabon’s new President, Albert-Bernard Bongo, circa 1965…and then there’s Halliburton, nuclear weapons, secret societies. Who is Omar Bongo really?

In September 2003 the National Geographic unveiled the first in a series of feature stories about the world’s ‘least spoiled’ and ‘most threatened’ tropical forests. The ‘Saving Africa’s Eden’ series showcased elephants walking on white sand beaches, silverback gorillas in lush greenery, and hippos surfing in the salty sea. Omar Bongo—“a self-possessed man with a wide mustache and a warm smile”—was the African hero who created thirteen new national parks literally overnight.

The National Geographic series followed the adventures of the requisite modern day white-skinned Tarzan personified by American biologist J. Michael Fay—the ‘man who walked across the continent of Africa’—and photos showed Fay trekking through the equatorial jungle, crisscrossing savannahs and, later, surveying the wilderness with the charismatic black-skinned then U.S. Secretary of State—fresh out of a helicopter for a photo op—General Colin Powell.1

It was all so captivating that I got the idea I had to go there. And so I did. Intrigued by the stories in National Geographic —which I recognized as the propaganda of the corporate empire 2 —in late 2004 I took a ‘vacation’ from the beauty and bloodshed in the big Congo (Kinshasa) and hitchhiked across the (not-so) little Congo (Brazzaville) for a visit to ‘paradise’.3

From Libreville I flew to Gamba, in the south of Gabon, took a boat to Sette Cama, and spent Christmas 2004 with my base camp on a bluff some 50 feet above the ocean in Loango National Park, the jewel of Gabon’s largest new protected area, the 1,132,000 hectare ‘Gamba Protected Area Complex.’ It is also the heartland of Shell, Halliburton and Schlumberger oil corporations in Gabon.

“Blue seas, white sand, elephants, whales, sea turtles, monkeys, bush pigs, unbelievable scenery,” biologist Fay was quoted to say. “Gabon has it all. It has everything that everyone ever dreams about in paradise, as far as I’m concerned.”

J. Michael Fay was right, I said to myself, many times, surrounded by beauty and wildness, warm (90 degree) mists on the ocean and elephants on the beaches, soaring ospreys and chimpanzees falling out of trees, and the peace of the deserted shores of one of the most fantastic enduring wild places on earth.

But J. Michael Fay skipped the dirty details. Fay didn’t mention the poverty and suffering of black Gabonese villagers whose mud-hut and malaria suffering stands in sharp juxtaposition to the swimming pools and golf courses for highly paid white expatriates, sport fisherman or adventure tourists. Or that the Gamba Complex is a private zone controlled by Shell Oil, with checkpoints and guards, where pipelines, oil barges, well-heads and huge toxic flames burning off natural gas are more visible than the elephants. And the medical waste, dumped at sea, that litters the ‘pristine’ beach: one day I picked 48 syringes with 2 inch needles out of the white sand where I was walking barefoot. J. Michael Fay became a personal adviser to Omar Bongo, but he didn’t tell us about the terror Gabonese people live and die with.

“It [‘Saving Africa’s Eden’] is unbelievable,” Marc Ona Essangui told me, in Libreville. It was just like another film about Africa.” In April 2009, Marc Ona received the Goldman Environmental Prize 4 for his selfless grass roots struggle to exposing corruption and human rights violations and protect Gabon’s environment, and he was threatened, arrested and illegally detained by the Bongo government.

“They announced that setting up these new Gabon parks would bring one million tourists a year, but even Kenya couldn’t do that. The pictures in National Geographic suggested that it’s easy to encounter these animals, but it’s not. It would take many days. Even though the whole world may perceive that conservation is proceeding in Gabon, this is not the reality.”

“Why did Bongo create [gazette] these thirteen new reserves? Because of scandals that took place in the past few years, like the financial scandal with FIBA Bank and the fraudulent presidential elections here, and to create tension and play off the United States against France. Bongo needed to find some way to repair relations with the United States.”

Welcome to Gabon, a small otherwise unheard of Banana Republic in equatorial Africa. Hippos in the surf… gorillas in the mist… the adventures of the great white Tarzan, National Geographic Society explorer-in-residence, J. Michael Fay, “the crazed American, the wild child who footed his way across all those nearly impassable forests and swamps, who sat half-naked atop the Inselbergs, who brought back photos and tales of a Gabon that Omar Bongo himself hadn’t known existed.” 5

Now he’s bushwhacking through tropical lianas and serpent filled trees with machete… now’s he wading through leech-filled crocodile swamps… his trusty negro porters and trackers at hand… now he’s being gored by an elephant… Welcome to the state-of-the-art cartography and explorer-conqueror genre: Fay’s private helicopter almost daily dropping supplies in the jungle to the tune of hundreds of thousands of U.S. taxpayer dollars and mom & pop conservation donations…

|

Controlled by French Companies since 1900, Gabon's corrupt logging sector is the second largest income earner. One goal of the Congo Basin Forest Partnership is to facilitate U.S corporate access to Gabon woods to 'sustainably' plunder Eden. Over 600,000 m3 of logs are annually exported illegally. Photo Keith Harmon Snow, Gabon, December 2004.

The coup des gras on all this propaganda was the portrait of Omar Bongo—the altruistic African President more interested in saving the environment than selling it off for the glitter of gold or the bling bang of diamonds or for parquet floors and plywood. President Omar Bongo was portrayed as the intent listener, the wise philosophical leader, the humanitarian negotiator. He was not—according to the spin-doctors of the propaganda system—your usual African dictator who packs people’s severed heads in his refrigerator (Idi Amin) and later has his ears cut off (Samuel Doe).

The National Geographic photos of Eden unveiled were splashed all over cyberspace. Films were made and speeches given to capitalize on the momentum of public interest. Maps and guides were mass produced, DVDs and coffee table picture books, interactive features—even “classroom companion African resources” to properly influence the kiddies. The travel agencies jumped on board. Everyone was echoing the mantra: “Could Gabon be the next ecotourism destination?”

The National Geographic series was a sort of public relations pitch for the big money conservation non-government organizations—Bi(g) NGOs or BINGOs—who get all the funding: corporate entities like World Wildlife Fund, Conservation International, Fauna and Flora International, and the Wildlife Conservation Society. But the series also introduced and paved the way for the Congo Basin Forest Partnership (CBFP), a predatory USAID 6 initiative involving some seven African countries, U.S. logging companies, NASA, the Pentagon and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, launched under President George W. Bush.7 In 2002, Walter Kansteiner, U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs, paid a six-day visit to President Omar Bongo to negotiate the CBFP, and “Saving Africa’s Eden” whitewashed the Kansteiner story as falsely as they did the Bongo regime.

National Geographic was selling ecotourism and wildlife protection as a panacea to ‘save’ Africa’s idyllic gardens of Eden. But it was all a smokescreen, a blanket of propaganda draped over the primitive realities of the country of Gabon. The script was written by big business masquerading as conservation: the Wildlife Conservation Society wrote Colin Powell’s speeches, delivered in Johannesburg. Kansteiner was described as a humanitarianism possessed with the need for democracy, health care and peace, but the Kansteiner family profits by exploiting Africa as ruthlessly as King Leopold. Trading in columbium tantalite (coltan) out of the bloody Kivu provinces of D.R. Congo, Kansteiner is also a director of Moto Gold, a company that sprouted out of the genocide in the DRC’s bloody Ituri districts.8

Today the blanket of propaganda is being draped over the casket of Albert-Bernard Bongo, the elfish little man who for forty-one years ran the country of Gabon as a private enterprise for himself, his family, his foreign backers and protectors. Articles that mildly illuminate the corruption of the Bongo government merely serve to distance Western governments and cover for multinational corporations and state sponsored terrorism by blaming everything on Bongo.9

This was not my first visit to Gabon. In 1997 I was focused on the murder of Ken Saro Wiwa and the petroleum genocide in the Niger River Delta.10 I wanted a visa for Nigeria, and I passed through every country around or near Nigeria trying to get one. But the country was closed under dictator Sani Abacha—the butcher—and I was too frightened of Nigeria to enter the country without a visa.

Ghana was an Anglo-American stronghold, but the others I passed through were all Francophone dictatorships: Burkina Faso, Niger, Benin, Togo, Cameroon—and Gabon. It was a wake-up call to the structural violence that enslaves Africa and enriches the West and its comprador class agents like Omar Bongo.11

In Libreville I met Thierry (not his real name). Thierry quietly told me he had worked in human rights until he became a very outspoken critic of the government. He was on the run, living ‘underground’ and existing by moving, one day to the next, through networks of friends. He was an intellectual, and he described a climate of terror in Gabon involving extra-judicial executions, disappearances, torture, all run by Bongo’s intelligence operatives and the Deuxieme Bureau, also known as the Service de Documentation Extérieure et de Contre-Espionnage (SDECE), the French secret service.

The most egregious repression occurred in 1990, Thierry said, when civilians were massacred during the ‘pro-democracy’ protests in Port Gentil. The true human rights situation is hidden, he said, even after numerous letters were sent to Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch.

“President Bongo knows everything that goes on in Gabon,” said Thierry. “Everything. Nothing happens that he does not know about. And there are very sophisticated forms of terror, like torture, disappearing, ritual killings, using plain-clothes operatives, in designer blue jeans or NIKE tracksuits. Bongo knows all about it—he is involved—and they have killed a lot of people with no one knowing about it. People just suddenly disappear or turn up dead.” 12

A white woman named Catherine who worked in language translations confirmed the 1990 massacres. “There are a lot of things you can do in the United States that you cannot do here,” Catherine told me, acerbically, “and one is to be politically curious. You just don’t go around asking these kinds of questions here. You would never get away with it but even if there was an attempt to investigate the massacres it would be blocked.”

I also met a white expatriate consulting in the oil sector. He had just come from Port Harcourt, Nigeria but he shuffled around between Cameron, Nigeria, Gabon and Angola. “Foreigners who work in Gabon work in wood or in oil,” he said. He confirmed that killings were routine before the mid-1990’s, and that massacres occurred in Port Gentil just as Thierry had said. He said that the stories about protestors being arrested and tortured were true. “It was not just a few people killed,” he insisted. “It was a lot of people. Protestors were taken out over the ocean in oil company helicopters and pushed out, alive or dead. It’s more than just a rumor.”

Togolese and Nigerian refugees in Benin, human rights activists in Cameroon, all have described these terrorist tactics involving petroleum sector helicopters. One Togolese refugee explained that in Togo they didn’t just push people out, they hang them from helicopters and fly low over the ‘jungle communities’ to instill them with terror.13

“Bongo used to just kill anyone he wanted, openly, before 1990,” a local Gabonese man, Maconi, told me in Libreville. Maconi’s family is involved in the timber sector in Gabon, and his mother is French and he moves within the French community. “Bongo would just kill them without trying to keep it quiet. Now [2004] it is different, it is subtle, quiet, you don’t see it, but it hasn’t stopped.”14

...to be continued next week

Footnotes

1 See: David Quammen, “Saving Africa’s Eden,” National Geographic, September 2003; J. Michael Fay, “Gabon’s Loango National Park: In the Land of the Surfing Hippos,” National Geographic, August 2004; Quammen, “Views of the Continent,” National Geographic, September 2005; and J. Michael Fay, “Ivory Wars: Last Stand in Zakouma,” National Geographic, March 2007.

2 E.g., Catherine A. Lutz and Jane L. Collins, Reading National Geographic, Univ. of Chicago Press, 1993.

3 The Gabon mission was partly funded with a small grant from the Rainforest Foundation U.K.

4 http://www.goldmanprize.org/2009/africa.

5 Quammen is one of the Outside magazine editorial gang (David Quammen, Donovan Webster, Jon Kracauer, Randy Wayne White) who guided Outside when it went astray of any substantive reportage in the late 1980’s, becoming a corporate travel and beauty rag, and who now unquestionably serve the Empire in producing whitewashed features about Africa for National Geographic, IMAX cinema productions, Vanity Fair, Smithsonian, New York Times Magazine, and other white institutions; their reportage has been directly funded by big corporate entities. See, e.g.: David Quammen, “Saving Africa’s Eden,” National Geographic, September 2003; Quammen, “Tracing the Human Footprint,” National Geographic, September 2005; Donovan Webster, “Journey to the Heart of the Sahara,” National Geographic, March 1999; “USADF Hosts Writer & Editor Donovan Webster as Part of Distinguished Lecturer Series: Talk Focuses on Water Projects Funded in Niger by USADF,” http://www.adf.gov/USADFUSADFHostsWriterandEditorDonovanWebster.htm.

6 United States Agency for International Development—another Pentagon-intelligence conduit.

7 CBFP involves too many agencies, countries, corporations and NGOs to list here.

8 See: keith harmon snow, “Merchant’s of Death: Exposing Corporate-Financed Holocaust in Central Africa: White-Collar War Crimes, Black African Fall Guys,” Black Star News, December 4, 2008.

9 See, e.g., “Omar Bongo,” The Economist, June 18, 2009, http://www.economist.com/displaystory.cfm?story_id=13855223

10 Ike Okonta and Oronto Douglas, Where Vultures Feast: Shell, Human Rights, and Oil, Verso, 2003.

11 An excellent writing on the nature of race relations and control is: Frances Nesbitt Njubi, “Migration, Identity and The Politics of African Intellectuals in the North,” Paper Prepared for CODESRIA’s 10TH General Assembly on “Africa in the New Millennium”, Kampala, Uganda, 8-12 December 2002, http://www.codesria.org/Archives/ga10/papers_ga10_12/Brain_Njubi.htm.

12 Private interview, “Thierry,” Libreville, Gabon, 1997.

13 Interviews with Togolese refugees, Cotonou, Benin, 1997.

14 Private interview, Maconi, Libreville, Gabon, December 29, 2004.