The Crimes of Bongo Part II

Apartheid & Terror in Africa's Gardens of Eden

By Keith Harmon Snow

Keith Harmon Snow is the 2009 Regent's Lecturer in Law & Society at the University of California Santa Barbara, recognized for over a decade of work, outside of academia, contesting official narratives on war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide while also working as a genocide investigator for the United Nations and other bodies. He is also a past and present (2009) Project Censored award winner.

PARISTROIKA

From the very beginning, circa 1865, Gabon was the focal point from which France projected its military and economic power across the continent, serving as an intelligence-gathering base much as Burkina Faso has historically served that role for Israel and the Congo (Zaire) has for the USA. In fact, France forced Gabon’s independence movement to accept France’s full economic control as a pre-condition for ‘independence’.

Gabon’s first President Leon M’ba—and his early one-party dictatorship—set the stage for the Bongo regime both through sheer corruption and the Gabonese state’s nefarious military and intelligence alliance with the French. A rapid intervention by French Foreign Legion commandoes secured M’ba’s presidency after an attempted coup d'etat in 1964: M’ba was said to be a close friend of Charles De Gaulle. Many of Mba and Bongo’s French supporters considered Gabon their private domain and were threatened by Gabon’s ‘independence’ after decades of French colonial occupation. When M’ba died of illness, Bongo took the reins and with the help of France he consolidated absolute power: one of the fledgling President’s first actions was to immediately dissolve all political parties and replace them with the ‘Democratic Party of Gabon.’

Charles de Gaulle and his ‘Monsieur Afrique,’ Jacques Foccart directly installed Bongo in 1967. Bongo was the choice of a powerful group of Frenchmen—the Clan des Gabonais—composed of key members of the French government and influential Gabonese in alliance with strategically placed French nationals who controlled the economy of Gabon.15 Foccart maintained French control in the former colonies through the Reseau Foccart, an intricate ‘network’ who collaborated with the French military and major French economic interests to guarantee access to strategic minerals. Former French ambassador and close M’ba adviser Maurice Delauney was a central figure in the Foccart network and the man who handpicked Bongo as Mba's successor. 16 French mercenaries and legionnaires like Bob Denard were (and remain) members of the Clan des Gabonais, using Gabon as home base for intelligence, covert operations and terrorism from Sao Tomé to Madagascar. 17 French soldiers operate within the Gabonese military and French pilots in the Air Force; elite Mirage and Jaguar aircraft from the French air force are based on the military side of the Leon Mba airport in Libreville.

Petroleum exploration in Gabon was begun in the early 1930s by the French national oil company and Gabon was the first African country to host French oil giant Elf in the 1960s, from where Elf operated as a state within a state, serving as a base for French military and espionage activities, and for many decades Libreville remained the French nerve center of covert operations in central and southern Africa. 18

Shell Oil Corporation began explorations in Gabon in 1960 (and Nigeria in 1958). Other oil companies in Gabon today include: AGIP (Italy), Amerada Hess (USA), AMOCO (US), BP (British Petroleum), Occidental Petroleum (USA), Energy Africa Gabon (South Africa), Pan African Energy, Marathon Oil (USA), Exxon/Mobil (and subsidiary Esso Exploration West Africa), Broken Hill Petroleum and Tullow Oil, a U.K.-based profiteer also involved in war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide in eastern Congo and Uganda. 19 The French oil conglomerate Total acquired Belgium’s PetroFina in 1999, and Elf -Acquitaine in 2000, creating one of the world’s nastiest multinational oil companies.

For almost 50 years, France’s entire international security policy—its classified nuclear weapons strike force and atomic reactor complex, le force de frappe atomique—revolved around uranium from Gabon and Niger. Production in Gabon began in 1961 through the Compagnie des Mines d’Uranium de Franceville (COMUF), a consortium involving multinational corporations like Total and AREVA. COMUF is 68.4% owned by French multinational COGEMA, which is also one of Canada’s largest uranium producers; COGEMA is partnered with the U.S. Department of Energy in the production of nuclear fuel for the U.S. weapons complex. The infamous U.S. multinational Union Carbide, responsible for crimes against humanity in Bhopal, India, was heavily involved in another catastrophe: uranium mining in Gabon. A local hospital near the remote Mounana uranium mine has documented the long history of under five children living and dying with disfigured bodies, gynecological tumors, blood and skin diseases, cancers and leukemias, or the epidemics of radiation poisoning that quietly obliterated so many adult miners over 38 years of operations. 20 It is the same, ugly story in Niger, only uglier, due to higher populations of Tuareg and Toubou nomads, and the same imperial realities of uranium are hidden by the same National Geographic writers. 21, 22

Also involved in uranium in Gabon are: Motapa Diamonds (U.S.A.); Mineral Services International (Cape Town, Vancouver, London, Gaborone and Libreville); Pitchstone Exploration (Canada, U.S.A.) and CAMECO (U.S.A., Canada)—a DeBeers connected company also tied to the Washington D.C. law firm Winston & Strong. 23, 24, 25

Manganese is essential for superalloys essential to the western aerospace and defense complex: Gabon is the second largest producer behind South Africa and manganese is Gabon’s third largest export earner. U.S. Steel owned 44% of Gabon’s manganese producer, the Compagnie Miniere de l’Ogooue (COMILOG), which U.S. Steel set up with France in 1953; U.S. Steel reportedly sold out in the 1960’s, but 60% of COMILOG was controlled by French and U.S. interests until 1996 when Eramet Group (France) bought 57%, leaving the Gabon government with 27% and ‘other private parties’ (read: U.S. & French businessmen) with 16%. 26 COMILOG has a capital value of over $80 billion and its profits soared from US$ 4.2 million in 2003 to US$ 183 million in 2004; about one-third of COMILOGs production is used by Eramet's manganese plants in France, Norway and USA (two-thirds goes to China, India and Ukraine).

COMILOG also controls the TransGabonese Railway—crucial to the massive devastation of rainforest logging. (Due to heavy metals emissions, Eramet Marietta is under fire in Ohio and West Virginia for epidemics of disease.27 ) Repression in the logging sector in Gabon is widespread: foreign companies penetrate rural areas, dividing and conquering forest people with cash and conflict, bringing alcohol, hunting, prostitution, traffic in endangered species, and direct paramilitary violence. The entire western NGO (e.g. BINGOs like WWF, WCS, Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund, the Great Apes Survival Project, Jane Goodal Institute) narrative on the ‘bushmeat trade’ ignores the role of state repression backed by western institutions and the private profits and white supremacy of the BINGOs. 28

Directors of the mighty French nuclear conglomerate AREVA also serve on the boards of Lloyd’s of London, Goldman Sacs (USA), Power Companies of Canada, Euro Disney, Total Oil and others. AREVA’s connections to the Belgian establishment include intelligence insider Viscount Etienne Davignon, a man deeply tied to the depopulation of the Congo (DRC) through his long-time directorship of Belgium’s Societé Generale—one of the DRC’s longest and most lasting enemies. Davignon is also an affiliate of Donald Rumsfeld and George Schultz through Gilead Sciences, a U.S. biowarfare pharmaceutical firm, and he is a director of Kissinger Associates. Davignon was Belgian Minister of State during the ‘independence’ transition and the installation of Colonel Joseph Mobutu. A 2001 Belgian parliamentary enquiry concluded that Davignon played an important and active role in the assassination of Patrice Lumumba. 29

|

|

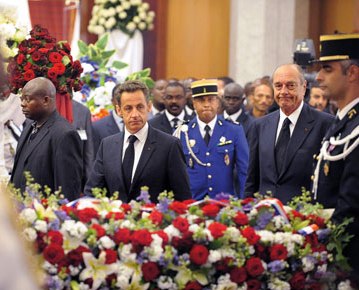

French President Nicolas Sakozy (2-L) and former French President Jacques Chirac (3-L) pay their respects before the coffin of former President of Gabon Omar Bongo at the Presidential palace in Libreville on June 16, 2009. Photo by AFP/Getty Images |

Successive government’s of Japan have also supported the corruption and terror in Gabon through mining and oil and direct financing provided by Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) to the Bongo regime. 30 Mitsubishi holds four major petroleum concessions, one in partnership with Tullow Oil, but Gabon was also critical to Japan’s nasty atomic reactor industries.

The stranglehold of the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) economic austerity plans led to civil unrest as labor taxed, wages were cut, education and public health sectors, never much to begin with, were gutted. By the late 1980’s Bongo was overseeing a massively oppressive regime predicated on state terror backed by France and, more poignantly, multinational corporations.

With the fall of the Berlin wall and the Soviet Perestroika the veneers of stability in Gabon gave way to deep, festering wounds of decades of state oppression: students, onshore oil workers, civil servants and the general public took to the streets in pro-democracy protests. It was the same story in Burma, South Korea, Indonesia and China, but only Tiananmen Square made the news: China is considered an ‘enemy state’ of Western predatory capitalism, while the others are client states. 31 It was the same story in Port Gentil and Libreville, Gabon as in Colonel Joseph Mobutu's Zaire, General Gnassingbe Eyadema's Togo, Paul Biya's Cameroon, and General Ibrahim Babangida's Nigeria: all Western client states which saw massive repression of civil society, with student massacres, 1989-1991. This state orchestrated terrorism occurred at Jos and Port Harcourt, Nigeria, and in Lubumbashi, Zaire (May 11-12, 1990), and massacres were covered up by the West and its propaganda system; subsequent student-government clashes in Zaire occurred in Kisangani, Mbuji-May, Bukavu, Kinshasa and Mbanza-Ngungu during the communications blackouts, and were never known to the world in any details.32,33 Meanwhile, Dennis Sassou-Nguesso and Omar Bongo collaborated with Mobutu to prevent all news of the Lubumbashi massacre from leaking out. And then, a few weeks later, Bongo had the same problem: corpses needing to be disappeared.

The violence in Gabon reached a local peak in March, April and May of 1990. Pressured to declare the ‘end of one party rule,’ Bongo and his one-party state set about to neutralize all significant opposition. The people protested fearlessly. The state terror apparatus clicked into action after foreign oil sector executives (e.g. Shell Gabon's director André-Dieudonne Barre) complained. 34

On May 21, 1990, France sent in several hundred elite paratroopers. Dubbed ‘Operation Requin’ (Shark), the rapid intervention forces of the French Foreign Legion 2nd Paratroopers Regiment (REP: 2eme Regiment Etranger des Parachutistes)—the elite of the world’s elite soldiers—were sent to support the French Foreign Legion Infantry Regiment (REI: 2eme Regiment Etrangere d'Infanterie) troops permanently based in Gabon. The REP was known to attach U.S. covert operatives on missions and is described as “some of the most skilled and dangerous soldiers on earth.”35

From May 21-30 some 500 French troops were dispatched to the luxury oil city of Port Gentil. Bongo, furious, arrogant and absolute, declared a ‘state of siege’ throughout the coastal province of Ogooue-Maritime, the only significant population center in the country. Quite literally overnight, key opposition leaders were assassinated or disappeared. But the French troops collected all French nationals at the Elf Corporation compound in Port Gentil and together with the Presidential Guard they battled with ‘rebel forces’ [read: civilian protestors]. The Presidential Guard was ‘credited’ with the killing and not the French troops —it is always black Africans who are credited with massacres in partnership with foreign troops. 36

|

|

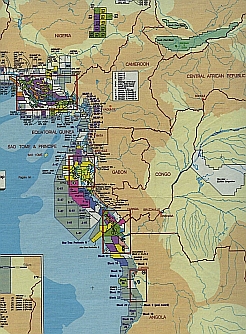

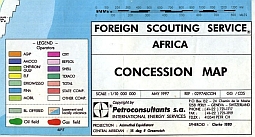

1997 industry map of oil concessions in the Gulf of Guinea and along the West Coast of Africa.Yellow blocks are ELF (see KEY on the right). |

While reporting that “several people had been shot in the unrest”—official reports today suggest only five dead 37—international media also reported that the Presidential guard crushed civilian barricades “deploying tanks, automatic weapons and grenades” and, in the last days, finally “began to round up demonstrators” amidst “continued intermittent gunfire.” 38 But people in Gabon report that at least 500 to 600 civilians (some Gabonese believe it was as many as 2000), many of them students, were massacred on the streets of Port Gentil-from May 21 to May 31, 1990-by the orders of President Omar Bongo. 39

|

The appearance of tolerance for any ‘opposition’ in the country was provided by a faux opposition connected to Bongo's and France's multinational corporate competition: any true opposition was bought off by Bongo and/or compromised by their participation in secret societies (like the Freemasons).40 The intelligence networks and terror apparatus targeted anyone unable to be silenced by bribery or blackmail. The long arm of Omar Bongo’s assassinations squads even reached outside Gabon: in 1996 one opponent of Bongo was assassinated in France on the orders of Libreville. 41

All so-called ‘elections’ that have occurred in Gabon (Cameroon, Togo, Nigeria, etc.) are demonstration elections meant to legitimize nasty dictatorships serving western capitals.42 Of course, President Omar Bongo Ondimba always won—in 1993, 1998 and, most recently, 2005—and Bongo’s foreign patrons characteristically whitewashed elections violence.

Meanwhile, Bongo visited the White House, and its counterparts in France, England, Belgium, Holland, Switzerland, Luxembourg, Canada, Germany, China and Saudi Arabia.

Military relations between the U.S., Canada, France, England and Israel on the one hand, and the dictators like Bongo on the other, continued throughout their decades long tenures, no matter their brutalities: under the Clinton Administration, for example, the Pentagon sent U.S. covert forces to train General Eyadema and Paul Biya’s elite killers under a new program, the Africa Crises Response Force (‘Force’ was later changed to ‘Initiative’ to soften it, transforming ACRF to ACRI); troops also trained at the Pentagon’s Special Operations School at Fort Hurlburt, Florida. 43

Bongo meddled in weapons and money-laundering: one of Bongo’s private arms dealers, Frenchman René Cardona, fell out with Bongo and was imprisoned in Gabon in 1996: a corruption investigation in France found that Cardona’s son paid 300 million CFA francs into Bongo’s personal account to buy his father’s freedom. 44

Gabon grew to become an unprecedented example of the success of the national security client state, where the offshore petroleum industry was designed to operate as an independent state, with its own private communications, transport, and supply chain infrastructure thus making offshore oil operations immune to onshore civil strikes or public protests. The oil operations grew to become islands of stability staffed by foreign expatriate labor and management, supplied by independent shipping and aviation, protected by elite networks of the foreign and domestic security apparatus.

To be continued.....

Footnotes

15 See: Nicolas Shaxon, “Gabon: Omar Bongo; Franco-African Secret Society,” The East African, June 22, 2009; “French Secret Services: African Debate,” Africa Confidential, date uncertain; James F. Barnes, Gabon: Beyond the Colonial Legacy, 1992; “Gabon: Oil, Money, Paristroika,” Africa Confidential, Vol. 31, No. 12, June 15, 1990.

16 James F. Barnes, Gabon: Beyond the Colonial Legacy, 1992.

17 See: Aidan Hartley, “Paradise Lost,” Africa Report, March-April 1990.

18 “French Secret Services: African Debate,” Africa Confidential, date uncertain.

19Tullow Oil, http://www.tullowoil.com/tlw/operations/af/gabon/. See: keith harmon snow, “The War That Did Not Make the Headlines: Over Five Million Dead in Congo,” Global Research, January 31, 2008; and keith harmon snow, “The Rwanda Genocide Fabrications: Human Rights Watch, Alison Des Forges, and Disinformation on Central Africa,” Dissident Voice, April 13, 2009.

20 See: “Gabon: AREVA sets up its observatory of health at Mounana,” Gaboneco, April 4, 2009; and

21 See, e.g., “Desert residents pay high price for lucrative uranium mining [Niger],” UN Integrated Regional Information Network (IRIN), March 30, 2009; and “Niger Uranium: Blessing or Curse?” IRIN, October 10, 2007, http://www.irinnews.org/Report.aspx?ReportId=74738.

22Donovan Webster, “Journey to the Heart of the Sahara,” National Geographic, March 1999.

23See: Motapa Diamonds web site: http://www.motapadiamonds.com/s/StrategicPartnerships.asp .

24Pitchstone Exploration Ltd., http://www.pitchstone.net/africaprops.htm.

25See: CAMECO, http://www.cameco.com/responsibility/governance/; and http://www.wise-uranium.org/uccam.html.

26James F. Barnes, Gabon: Beyond the Colonial Legacy, 1992

27Ohio Citizen Action, “Eramet Marietta Inc.,” http://www.ohiocitizen.org/campaigns/eramet/eramet.html

28The Jane Goodall Institute, for example, has directly backed war in eastern Congo. See the KING KONG series at http://www.allthingspass.com.

29Parliamentary Committee of enquiry in charge of determining the exact circumstances of the assassination of Patrice Lumumba and the possible involvement of Belgian politicians, Belgium, 2001.

30 “Gabon: Oil, Money, Paristroika,” Africa Confidential, Vol. 31, No. 12, June 15, 1990.

31On ‘enemy’ versus ‘client’ states see Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky, Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media, Pantheon, 1988; Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky, The Washington Connection and Third World Fascism, South End Press, 1979; William Blum, Killing Hope: U.S. Military & CIA Interventions Since WW-II, Common Courage, 1995.

32 There were “estimates of at least 100 killed” in Lubumbashi (see, e.g., “Zaire: Mobutu Takes to the Water,” Africa Confidential, Vol. 31, No. 12, June 15, 1990, pp. 1-3), but DRC experts attest to more than 2000 casualties as the murderous Division Spéciale Présidentielle massacred throughout the night on a campus with a student body of 7000 resident and 3000 external students. By the time the U.S.-based Lawyers Committee for Human Rights issued its 1990 report, the U.S. had “confirmed that one person had died” at Lubumbashi (see Zaire: Repression As Policy, Lawyers Committee for Human Rights, 1990).

33 Zaire: Repression As Policy, Lawyers Committee for Human Rights, 1990.

34 “Gabon: Opposition Leader’s Death Unleashes Riots,” Africa Research Bulletin, June 15, 1990.

35 See: Howard R. Simpson, The Paratroopers of the French Foreign Legion: From Vietnam to Bosnia, Brassey’s, 1997.

36 “Gabon: Opposition Leader’s Death Unleashes Riots,” Africa Research Bulletin, June 15, 1990.

37 See, e.g., Nicolas Shaxon, “Gabon: Omar Bongo; Franco-African Secret Society,” The East African, June 22, 2009.

38 “Gabon: Opposition Leader’s Death Unleashes Riots,” Africa Research Bulletin, June 15, 1990.

39 Interviews in Gabon, keith harmon snow, 1997, 2004.

40 See, e.g., Nicolas Shaxon, “Gabon: Omar Bongo; Franco-African Secret Society,” The East African, June 22, 2009; and Shaxson, Poisoned Wells: The Dirty Politics of African Oil, Palgrave, 2007: p. 75-78.

41 Africa Research Bulletin, Vol. 45, No. 3, March 2008, p: 17479.

42 On ‘demonstration elections’ see: Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky, Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media, Pantheon, 1988; Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky, The Washington Connection and Third World Fascism, South End Press, 1979.

43 “Africa-US,” Africa Research Bulletin, July 1-31, 1997, p: 12770. On ACRI, see Wayne Madsen, Genocide and Covert Operations in Africa, 1993-1999, Mellon Books, 1999, p. 251-257.

44 Africa Confidential, Vol. 48, No. 14, July 6, 2007.