Kwame Nkrumah: Authentic Legacy?

|

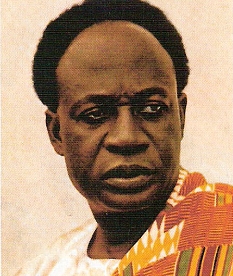

| Dr. Kwame Nkrumah Photo courtesy |

However, while Nkrumah’s Pan-Africanism was relevant to the African cause, it lacked original African cultural roots, thus failing to appropriate African values critically for the Pan-African project.

When some years ago people in Ghana's Northern Region told policy-makers to consult them and their values when making policies, they were in effect protesting against being sidelined in policy making, a terminal error dating back to Nkrumah's era. This is part of Africa’s Big Man Syndrome where the Big Men assume to know everything; cannot be challenged; and impose their will on Africans. This, from the inception of the Ghana nation-state, not only created a huge problem of trust in the development process but also reveals that Ghana started on a wrong footing.

The Pan-Africanism project, which pre-dates Nkrumah, was more or less an African diasporan vision to raise the injustices ex-African slaves were encountering in the diaspora; unite them, and explore the possibility of returning them back to Africa. Sierra Leone (the Krios) and Liberia (the Americo-Liberians) are some of the products. Of prominence in the diasporan Pan-African vision was the issue of politics of skin colour and Africa's marginalization in the international political economy.

Initially Pan-Africanism was more or less an ex-slave diasporan African project, lacking a deep sense of the continental Africa environment and other original African home-grown developmental nuances. The Pan-African project, therefore, didn't flow first from within continental Africa, and this may explain why it initially lacked the deep African cultural orientated paradigms needed for developmental goals.

As a student in the United States and Britain, Nkrumah experienced such racism and returned to the then Gold Coast with such baggage. Short of African home-grown developmental nuances, Nkrumah and his associates wandered around the world, like headless chicken, looking for developmental paradigms, from ex-Soviet Union-oriented socialism to Europe-leaning capitalism or something in-between, as if Africa has no history, cultural values and experiences in terms of progress.

Nkrumah and his associates overwhelmingly carried on with the ex-colonialists' development paradigms without hybridizing the enabling aspects of African cultural values and the ex-colonialists' legacies in the continent's progress.

It is therefore, not surprising that Nkrumah harshly marginalized the traditional rulers, one of the key frontline traditional institutions for progress. Africa’s traditional rulers, as Dr. George Ayittey of the American University in Washington D.C. would tell you, are hugely untapped human resource materials in Africa’s development process.

The colonialist suppressed African values and imposed theirs. They thought, wrongly, as today's international development literature would correctly tell you, that African values were “primitive” and that they were more civilized than Africans, and so the Africans should be “civilized.” The French, for instance, minted the “assimilation” project to “civilize” the African. It failed. Then they created the “association” one, which aimed to mix African native culture with that of the French. That was daisy also because it wasn’t done from African perspectives or by Africans themselves.

In the process, both enabling aspects of African values and the inhibiting parts were suppressed for so long that even the earlier elites who came to power, as their behaviour revealed, thought Africa had no values worth appropriating in national development. Senegal's former President, Leopold Sedar Senghor (October 9, 1906 – December 20, 2001), part of the Nkrumah's era, thought Africans are better at expressing their emotions than thinking. No doubt, some prominent Africans such as Y.K. Amoakoh, the former chair of United Nations Economic Community for Africa, have observed that Africa is the only region in the world where foreign development paradigms dominate her development process to the detriment of its rich values.

Nkrumah and his associates did not think first from within African values in their zeal to develop Africa. The Japanese, like other ex-colonies, faced similar challenges and were able to circumvent any attempt to either fully carry on with American foreign development paradigms or let the foreign paradigms forced on their development throat, as America's post-war occupying Governor of Japan, General Douglas MacArthur, attempted to do.

Like the Southeast Asians, Nkrumah and his associates, using their Pan-African project, should have first envisioned Pan-Africanism as development policy-maker, brewed from indigenous African values, and juggle it with foreign legacies.

Fifty-two years on, foreign development paradigms dominate Africa's development scene despite lots of energy, time, and money spent on the Pan-African project, creating huge distortions in the continent's progress. The disturbing implications are that not only was the enabling aspects of African values not appropriated openly in national development planning but, as former Ghana’s Minister of Health, Courage Quashigah, would tell you, they were no attempts to refine the inhibitions within African values that have been stifling progress for the continent's progress.

Nkrumah’s Pan-Africanism, in all measure, is however growing, notwithstanding the hiccups. The emerging success of the Economic Community of West African States (and other African regional bodies), noticeably in helping restore order in Sierra Leone, Ivory Coast and Liberia, after years of civil wars, is one example. The transition from the Organization of African Unity (OAU) to the present African Union (AU) is another in the sense of African unity. These examples and many more reveal that Nkrumah’s Pan-Africanism is not illusory but working, taking on new meanings and challenges that emanate from the values and experiences of Africans.