Rethinking Governance in Africa

|

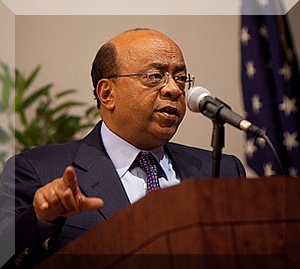

| Mo Ibrahim speaks on governance |

Three overlapping concepts: governance, democracy and leadership have increasingly captured public imagination. They have gained prominence because concern has developed regarding what constituted good governance in Africa in pre-colonial days. Driven by the anguish over Africa’s lost cultural values that anchored governance, people tend to be philosophical in discussing pre-colonial institutions that worked in harmony. Governance, they confidently declare, was a shared responsibility.

Colonialism, it is noted, transformed Africa socially and mentally by disrupting good value systems and declaring virtually everything African to be inferior. The disruption was so effective that it became almost impossible to resuscitate values. Those who became the new rulers of post-colonial entities tended to be externally beholden and allowed society to be manipulated. This partially explains the bad governance condition that Africa finds itself in, perpetuated by mediocrity in leadership and by constant “international” pleasure in stressing the negative on anything African. A rethink on governance in Africa is necessary to restore trust in the African self. This would require physical and mental vigour in confronting bad governance and recapturing the trust in the process of redefining governance.

Governance

Societies are organised ways of life or forms of governance in order to advance common interests that depend on environmental conditions and the effort mounted to improve life. While a lot of that effort is likely to be physical, it is the mental effort that is most important in ensuring the advancement of that particular organised society. To be organized, therefore, implies having a form of governance that regulates belief systems, customs and behavior, relations between people in that society, and the enforcement of accepted norms.

The question of governance also implies demarcated geopolitical jurisdictions, each limited to certain geographical zones beyond which other “governance” would have similar responsibilities. Governance, in this sense is a way of regulating and enforcing what is expected in a place and this calls for enforcement mechanisms. This means a system of formulating laws, procedures for settling disputes, the defense of values, and even rules on how to raise and educate children. All these are aspects of governance that are to be found in every organised living. Some governments are good and some are bad.

The question that arises, then, is on the type of governing structure that is best suited to particular peoples. Irrespective of the type, there are basics that must be observed. Most important is the protection and advancement of interests. This means proper assessment of a country’s relations with other entities and placing them in a geostrategic scale of importance relative to its interests. It starts with itself as the primary focus or the “centre” of everything and around which everything else should rotate. The survival and wellbeing of that “centre” becomes the determining factor in assessing the geo-strategic value of another place.

Every governing system should look at the concerns that can affect the “centre.” These include the interests of other geopolitical entities that can affect, positively or negatively, the well being of that state. It takes into account the relative distance from the centre and the kind of threats to be anticipated whether they are physical, economic, ideological, political, military or even cultural. It requires clear definition of who the “we” is that has to be protected from the “other.” These are issues to consider in redefining governance because governance in a place is not isolated from external forces. Each of the external forces, therefore, must be assessed as to their value relative to the interests of the centre.

Governance in a place hinged on the search of identity by people who claim to have a common ancestry that, in the course of evolution, acquired unique religious beliefs to explain themselves. Among those beliefs is the claim of divine anointment of an individual a legitimizing assertion that makes that individual unquestionable because to do so would be like questioning God’s wisdom. Such a ruler goes through religious rituals while instilling fear among the followers and survives in office by invoking God’s blessings as a way of legitimising what is essentially questionable governance. To do this effectively, rulers work hard to brainwash the people to accept and defend certain practices as part of their ritual, values and belief systems. Brainwashing and fear make it difficult to question the divinely appointed ruler. Such leaders, and their supporters, believe that they have good governance as an essence of governance.

Other than religious claims, good governance has also meant having a strong person ordering everybody around, for the good of the society. It is an elitist argument that preserves power to a select few and it is a logic that leads to what is called benevolent dictatorship. Basic to the rule of benevolent dictatorship is a lot of assumptions of good will and good-heartedness on the part of the “dictator”. The reality is that few rulers are good-willed or hearted or make decisions in the interest of the subjects.

It is the way that a ruler applies himself that often leads to claims that some are good and others are bad. In those few instances when they are good, “benevolent dictators” take credit, or are given credit, for being just, fair, and efficient. They avoid the duplicity of saying one thing and actually doing or meaning the opposite. The bad ruler thrives on the ignorance of people and enforces the laws selectively. His country lacks good governance. In general, when the public permit the ruler to decide everything because he is presumably wise, the end result is the hamstringing of the same public.

Democracy

If the rule by one individual is generally bad governance, the alternative has increasingly become “democracy”. Good governance has therefore been tied to “democracy” and tends to arouse different emotions. Although the two concepts have points of convergence, they are not necessarily the same. One of them, democracy, is a derivative of the other, governance. It is possible to think of governance without democracy but it is not possible to think of democracy without governance. In this sense, democracy is a form of governance that takes popular concerns into account before decisions are made.

In the notion of democracy, justice is the starting point because it is a basic criterion for governance if it is justly applied to all. The people in a given polity must agree on the broad principle of justice taking into account natural or god-given rights. The end result is an agreement on principles of justice, not the legalistic details. Governments, being creations of the agreement, must not contradict the principles and is then required to be “democratic”. This way, good governance is presumably assured through rotation of office and periodic elections.

The enforcement of the laws justly rather than legalistically is a whole-mark of good governance. This starts with the intent of the laws being proclaimed. Is it a pernicious intent aimed at repressing the citizens who are then required to choose between obeying a bad law and obeying their conscious? If the intent of the law is unjust, it becomes an instrument of bad governance once it is proclaimed. The tools of enforcement, meaning the police, the judiciary, and the prisons, then appear to be illegitimate even as they go about enforcing a law. An important element of good governance, therefore, is that the laws are accepted as being just in intent and in application. Deciphering the difference between what is legal and what is just is therefore at the centre of the very notion of good governance because there is no such a thing as good governance where the justness of the laws is suspect.

Good democratic governance also entails efficient delivery of expected services to the citizens who pay taxes. Justice requires that citizens get value for their money since to be taxed continuously for non-existing services creates discontent and a feeling of deception on the part of those entrusted with the responsibility. What is even more, there evolves a feeling that citizens should refuse to pay the taxes in order to avoid supporting what they consider evil projects, to be unjust, and therefore undemocratic.

To be continued.

By Macharia Munene,

Professor of History and International Relations, United States International University.