Sudan Intrigues: Will the Center Hold? Part 2

|

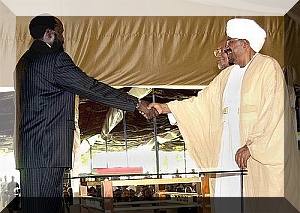

| A Pro-Bashir demo Photo courtesy |

The deliberate policy of internationalizing Sudanese issues, including the problems of the South, Darfur and the East, has undermined both national sovereignty and the national will. The regime has deliberately prevented the political opposition forces – which represented an overall majority at the last elections in 1986 – from playing a part in the resolution of national issues, as this would entail its implicit recognition of them. Instead, the regime preferred external mediation – specifically American and European – because of the sway of external pressures: all parties opposed to the regime have relations with the West, which could act as a driving force for them. It is striking that all the conferences and reconciliation meetings on Sudanese crises were held outside

Ironically, following the decision of the International Criminal Court (ICC) to issue an arrest warrant for President Omar Al-Bashir, the United States has begun to play a decisive role in steering and supervising the situation in

Secondly, there is the United States’ supposed influence among Southerners. Thirdly, there is an urgent desire to improve relations with

The United States finally designated a presidential envoy to Sudan, who changes depending on policy (the latest of these envoys is retired General Scott Gration), and whose role has grown closer to that of the High Commissioner in

A short time ago, Gration revealed that the American administration intended to send a permanent American team to Sudan to support the process of democratic transition and the elections, and to oversee the implementation of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement. This development follows the announcement of the Obama government’s strategy towards Sudan on October 19th, 2009, the preamble of which states that, “Sudan is at an important crossroads that can either lead to steady improvements in the lives of the Sudanese people or degenerate into even more violent conflict and state failure.Now is the time for the United States to act with a sense of urgency and purpose to protect civilians and work toward a comprehensive peace. The consequences are stark.

The declared strategic objectives consisted of: (1) a definitive end to conflict, gross human rights abuses, and genocide in Darfur; (2) implementation of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement; (3) ensuring that Sudan does not provide a safe haven for international terrorists.

This warning appears in the text itself: “It must be clear to all parties that Sudanese support for counter-terrorism is valued, but cannot be used as a bargaining chip to evade responsibilities in Darfur or in implementing the Comprehensive Peace Agreement.”

It is notable that the issue of democratic transition was not a clear priority in the American strategy. However, after the confrontations in parliament and the forced passage of the National Security Act, the Americans realized the difficulties involved in achieving their three objectives without genuine democratic transition. In subsequent statements made early this year, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton warned of serious threats to the progress of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, indicating that genuine democratic transition remained a distant prospect.

She held the NCP responsible for the slow implementation of the agreement, and called for the laws that limit freedom of expression, assembly and peaceful protest to be repealed.

To be continued.

By Haydar Ibrahim

Director, Center for Sudanese Studies.

Source: Arab Reform Initiative. http://www.arab-reform.net/