White Migrant Workers in Kenya:X-pats or Illegal Migrants?

|

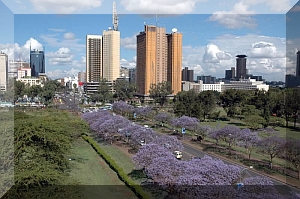

| Part of Nairobi city |

This wide class of wealthy people is not comparable in size with any other city in the region, thus making

Many employers still prefer European/North American candidates. A postgraduate degree in

While the Kenya government supports retired people or returning tourists who come and spend their money in

European Northern-American migrant workers are conventionally labelled expatriates or X-pats. The name evokes a cosmopolitan life of luxurious services as advertised by X-pats magazines and X-pats exclusive parties. Without denying the evidence that this is a privileged class, this article is an attempt to deconstruct the image of this class and show how many X-pats are in fact illegal economic migrants. The following examples present some of their stories and the strategies they deploy. The three-month tourist visa, renewable for another three months, is the main tool used by these migrants.

George, a free lance journalist, has been in

Marisa, 30 years old, has an NGO that offers services (such as event organization and production of documentaries) to other organizations. She has also been using tourist visas. On her last arrival in

Giselle, 28, is the foreign correspondent of an important media group. After years of illegal limbo, she paid a well connected person in the immigration office to get her a work permit as a consultant as “bribing was the only way to get a work permit.” The only problem is that now she has two governments asking her to pay taxes, the Kenyan and her own. Anne, 29 years old has a beautiful 2-year-old daughter with her Kenyan partner. Since they are not married, she is not entitled to stay in

Europeans get a new passport every one-two years so that the immigration officers cannot immediately see the number of Kenyan visas on their passports. However, the immigration office is adopting computer technologies which will render this expedient ineffective.

As a result of a strong alliance between the Church and the Kenyan Government, missionary congregations enjoy a special status. As long as they can demonstrate they have skills useful for the country (a University Degree is normally enough), they can get a missionary permit which does not allow paid work. Many NGOs who have projects or partnerships with missionaries congregations use this channel to get their employees work permits, as explained by Alex, 27 years old, who is managing the logistics of an NGO operating in South Sudan from Nairobi.

Being a student, as long as my research is approved by the Government of Kenya and I am given a research permit, I am entitled to a student visa. However, I have spent more than a week going to the immigration office just to be told to come back another day without being given the chance to speak or explain why I was there. This reminded me of the racism faced by legal migrant friends in

When I expressed to a friend my difficulties in getting a student visa despite paying expensive fees and fulfilling all the requirements, she answered that she admired my obstinacy to go the ‘legal way’ without bribes. She explained that no one will ever ask a white person to show his/her passport and he/she can always say that it is in the hotel because she did not want to have it stolen. In the worst case, a small tip will stop further questions. Most of her European friends were in

In almost three years in

llegal X-pats also share the anxiety of their illegal status and their increasing difficulties to face immigration authorities making it a common topic at X-pats Sunday’s picnics. Many of them belong to a generation of well-educated and prepared youth that in their home countries, especially Spain and

This migration has many complex interconnected causes that range from cultural interests to an exotic orientalist attraction for Africa. In essence it is an economic migration based on the quest for better quality of life that a young European can enjoy in

The issue of illegal white migrants in Africa is an underestimated and understudied emerging phenomenon which opens new research trajectories. In particular, it can challenge current beliefs of ‘black invasion’ of Europe and emphasize the fact that people have always migrated in any direction despite opposing legal framework. There is need to rethink migration policies globally; not only as a problem affecting Europe as incoming country but as a bidirectional issue.

In a world of free movements of capital and goods, only people are still facing constraints to their movements. Only by opening up European and African borders to foreign workers and recognising their contribution to national economies can we mutually and fully benefit from this exchange.

By Andrea Rigon

Government of Ireland Research Scholar in the Humanities and Social Sciences at