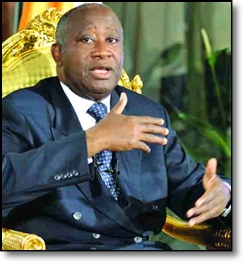

Laurent Gbagbo: Epitome of 'Big Man Syndrome'?

|

| Laurent Gbagbo |

Despite having a PHD in History, the African political diseases have destabilized Gbagbo’s rationality. In Cote d’Ivoire’s politics, these are toxic issues. Gbagbo is from the Bete ethnic group. Ouattara is from the Dioula ethnic group. Gbagbo and his associates from the south see Ouattara and his group from the north as “foreigners” or immigrants.

Clouded by tribal thinking, both the Constitutional Council; the southern elites and the military threw away the security of the country and the Ivoirian realities. They inverted the impartiality of the Independent Electoral Commission that is supervised by the United Nations and that said Ouattara had won the presidential run-off with 54 percent of the votes.

Security and political experts such as Knox Chitiyo (Head of the Africa Programme at Britain’s Royal United Services Institute) may give all sorts of compelling reasons for the Cote d’Ivoire imbroglio. Chitiyo told the BBC that “a number of complicating factors may lead to a protracted struggle” that will “stiffen Laurent Gbagbo's resolve.”

The complications come from Gbagbo and his associates, and the African political diseases of tribalism and the Big Man syndrome have consume them. Ivoirian elites have not been able to extricate themselves from these political diseases that are eating away beautiful Cote d’Ivoire and driving it towards self-destruction.

Drenched in the African Big Man syndrome, Laurent Gbagbo, 65, looks down on the likes of Ouattara, 68, whom he and others see as less of an Ivoirian because of his ethnic background. It doesn’t matter whether Ouattara was a former Prime Minister. Add tribalism to the egoistic African Big Man syndrome and you get a Cote d’Ivoire in eternally unpredictable chaos. Gbagbo, who has ruled for ten years, is expected to know better and do away with such warped thinking.

Labelling some ethnic groups as more Ivoirian than others doesn’t reflect the African reality. In the real Africa, no ethnic group is more of an African than the other. Gbagbo’s Bete is no more African than Ouattara’s Dioula. No matter what most of the politicians said during the general elections about the evils of tribalism, tribalism is a fatal issue in Cote d’Ivoire’s politics. The patterns of voting reveals this.

The Ivoirian presidential election controversy has opened debate on where the entire Ivoirian, and for that matter African, ethnic groups came from. They are all the same culturally and have been migrating within the continent for thousands of years, mixing with each other along the way. Their differences are basically geographical, as Prof. Jacob Ade Ajayi, the renowned Nigerian historian and editor of General History of Africa (1989) explains.

In an era of international multiculturalism; United States' President Barack Obama African (Kenyan) and European origin; Botswana President Ian Khama's blend of African (Botswanan) and English (Ian was actually born in Chertsey, Surrey, United Kingdom) heritage; and of Ghana’s ex-President Jerry Rawlings, a fusion of African (Ghanaian) and Scottish, the “Ivoirity” issue reflects some of the unrealistically doubtful policies running Cote d’Ivoire’s and Africa’s development processes and a terrible indictment on African humanity and civilization.

In African culture (and sociology) if you have a drop of African blood, you are African. It doesn’t matter which other racial blood drop you have. That’s why Rawlings and Khama are accepted. Ivoirian elites who perpetuate erroneous thinking stand condemned by African civilization and humanity. The troubling political crisis where there are two sitting Presidents in Abidjan – Laurent Gbagbo and Alassane Ouattara - reveals the dangers of the “Ivoirity” identity issue, in contradiction to the on-going global multiculturalism. It is a shame to Cote d’Ivoire elites, 50 years after freedom from France rule.

The cultureal tenets driving the over 65 ethnic groups in Cote d’Ivoire are practically the same (holding geography constant) and could be skillfully appropriated to resolve the Ivoirian uniqueness controversy way beyond the Gbagbo and the Ouattara presidential storm. They could also be used for grander local, national and continental progress. For the larger progress of Cote d’Ivoire, the over 65 ethnic groups that form the country need each other more than any of them imagine.

In his university school days (at Abidjan, Lyon and Paris), Gbagbo was called “Cicero,” after the Latin orator, because of his love of Latin studies. Gbagbo might help Cote d’Ivoire and Africa by re-orientating himself in new pathways in African historiography so that we can re-nickname him “Ajayi.” This will help him comprehend Cote d’Ivoire and Africa better and avoid uncalled for chaos.

When this happens, Gbagbo’s new thinking may help Ivoirians and Africans to look clearly at the whole poisonous ethnic and Big Man syndrome problems both culturally, morally and intellectually, as if it is for the first time that they are experiencing such troubling incidents, and use its refined end-products in the on-going African enlightenment processes for progress.