London Riots: A Case of Double Standards?

|

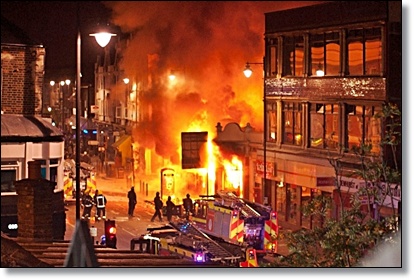

| London burning Photo courtesy |

While criminal procedure invented by 17th century capitalist societies convinced suspects that they are innocent until proven guilty, this legal presumption only holds validity under standard conditions of political temperature and in the absence of social pressure. The accused person - whether guilty or not, whether issues are relevant or irrelevant or testimony is admissible or inadmissible - is confined to an adversarial trial process by answering questions in binary form.

It is not possible to use abstract forms to control the social behaviour of riotous mobs. Amid chaotic crowds, liberties are safeguarded through brute force and repression to impose order. Thus British Prime Minister David Cameron responded to recent riots in England by authorising not only the use of rubber bullets and water cannons to protect property against looting and arson – but also the disruption of mobile phone communications. David Cameron's domestic repression of London demos can be used to assess Britain's foreign policy towards developing countries’ internal security polices.

On one hand, Cameron’s use of force is justifiable in light of the inherent limits of rule by law. To contain anarchic situations and prevent or deter existing threats, proportionate force may be necessary. On the other hand, questions arise as to what the causes of the spontaneous social protests are and what long-term measures should be implemented to address underlying social disorder. In such situations, a Commission of inquiry is likely to be established to improve on the Scarman Report on Brixton riots (1981) and the MacPherson Report (1999) which recommended diversity in police handling of complaints and rooting out of institutional racism. It is not clear whether these recommendations were implemented by aggressively recruiting ethnic minorities into the force or whether “stop and search” laws and “profiling” of ethnic minorities on mere suspicion are still commonplace.

Are the current UK riots race-driven or class-driven?

The current riots in Britain are no different from those afflicting other regions of the globe attributable to factors of “globalization.” Shelly Wright, in International Human Rights, Decolonisation and Globalisation (2001) attributes disruptive riots in Seattle, Melbourne and Quebec City to the uneasy relationship between the “late 20th century expansion of economic trade and financial arrangements across international boundaries” which challenge state sovereignty. These twin challenges comprise first, “political and legal globalization through international law, labour law, human rights law and environmental regulation.” Second, economic globalization. It is necessary to understand the social, economic and political environment in which labour peace has prevailed in Britain in order to evaluate what new policies may be required to redress the existing malaise.

During the Industrial Revolution, the first and second estates – consisting of nobility and clergy – conspired to retain the trappings of power and privilege accorded to elites. Unlike in France or Russia, social revolution was averted in Britain by neutralizing the third estate or commoners through co-opting the “labour aristocracy.” First, because religion, which Karl Marx accused of being “the opium of the people” endorsed slave labour, thus subsidizing the exploited classes. Second, because the colonial project consolidated British imperialism to elevate national pride above class consciousness. However, the British Empire sowed the seeds of its own destruction. Liberal justice presupposes that all citizens are equal before the law. This core common law principle was disregarded by colonial governments most unfortunately.

Take the Kenyan case of Commissioner of Local Government, Lands and Settlement v Kaderbhai [1931] AC 652 in which the Commissioner gave notice of sale by auction of plots at Mombasa. A British-Indian subject who had participated in railway construction as expatriate labour successfully challenged the restriction preventing non-Europeans from bidding. However, a discriminatory decision on appeal to Privy Council, reversed the East African Court and endorsed – not only the racial bar – but also the special condition that houses built on the land could not accommodate either Africans or Asians, except as domestic servants. Such racial segregation policies ultimately undermined the colonial enterprise conferring nationalists the moral high ground based upon the universal equality of human beings and democratic governance, which demanded majority rule.

Shaun Gabbidon’s Race, Ethnicity, Crime and Justice: An International Dilemma (2010) traces racial pluralism in Britain from the early 20th century upon an influx of about 150,000 Jewish nationals, which triggered the Jewish question. Riots erupted in 1919 as an expression that they had overstayed their welcome. Next, Afro-Caribbeans were on the receiving end of violent exclusion by the white majority during the 1950s. East African Asians became victims of Idi Amin’s aberration of Ugandan power in the 1970s that precipitated mass emigration. Inevitably, the surplus migrant population created pressure on social services – including jobs – culminating in the UK Race Relations Act of 1976. Under industrial society, liberal law combined with imperialism to effectively to contain class tensions and even foster hospitable race relations. However, the advent of globalization and the onset of post-industrial society, ushered in novel challenges. Ulrick Beck’s “risk society” recommends rethinking legal rules and policies in order to retain labour peace.

The question of who should get the plum jobs and how the national cake should be distributed, afflicts all countries. The landmark American Supreme Court decision in Brown v Board of Education (1954) 347 US 483 outlawed its fallacious “equal but separate” notion handed down in Plessey v Ferguson (1894). In the work context, the employer-employee equation became compounded when immigrants competed for equal pay for equal work to the detriment of indigenous Britons. Although the British society never formalized racial discrimination at home, it nevertheless prevaricated inexplicably – by simultaneously affirming equal rights for citizens irrespective of race – while denying equality to immigrants. Given the double standards in attitude, cultural diversity became variegated into first-class and second-class citizens.

British Home Office records disclose disproportionate disparities between minority blacks in its crime and justice statistics as evidence that they are not welcome among the white majority. According to the Sage Dictionary of Criminology, the phrase “moral panic” – first coined by criminologist Stanley Cohen (1972) – is defined as: “Disproportionate and hostile social reaction to a condition, person or group defined as a threat to societal values involving stereotypical media representation and leading to demands for greater social control and creating a spiral for reaction.” Cultural theorist Stuart Hall et al. in Policing the Crisis (1978) analysed social reaction to “mugging” or street crime. “Economically, this was a period of crisis in Britain. Politically, Britain’s standing in the world continued to decline and, domestically trade unions, left wingers and the welfare state were blamed fore much of the state of ‘sick Britain.’ New racial discourses were developed that of urban riots thus impact disproportionately more harshly against blacks.

Besides, the global backdrop corroborates moral panics regarding current riots in Britain from an international perspective. It is possible to extrapolate from the UK’s domestic criminal justice policy to its foreign policy on the international security plane. If at home “stop and search” arrests are disproportionately inflicted upon the underclass as second-class citizens and immigrants to maintain labour peace, then abroad, the third world countries become victims of western “crimes of aggression” under the guise of global peace-keeping. It is evident that international financial austerity has ramifications on human security, including peace. Yet the international community particularly the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) military forces appear to associate third world civil unrest and riots with black misrule or criminality rather than to failure of the capacity of liberal laws to sustain socio-economic equality. Ironically, Britain acquiesced in the Libyan bombings inflicting victimization upon President Muammar Gaddafi for taking repressive actions against his own citizens.

In the international labour relations context, the OPEC countries increase oil and petroleum prices to placate their dissatisfied populations. The world over, blacks bear the brunt of corresponding rising commodity prices and declining real wages. Some, like Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni resorted to brute force to restore order in repressing opposition leader Kizza Besigye’s walk-to-work protests. Others, like Kenyan President Mwai Kibaki conceded a power-sharing agreement, which elevated main rival Raila Odinga into Prime Minister. Given ethnic polarity, Kibaki therefore retains use of rule by law to suppress “Unga” (maizeflour) demonstrations, while cushioning consumers by controlling fuel increases. They leave the private sector and NGOs to donate famine relief dubbed “Kenyans4Kenya.” Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe similarly ceded Prime Minister’s powers to opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai, to avoid persistent civil conflict. Cameron’s Conservative party shares power with Liberal Democrat’s Nick Clegg too, but simultaneously endorses the need to deal with demonstrators drastically.

Whenever developing country leaders deploy violence against their own people, the West vilifies them as the “quintessence of evil.” Those arraigned before local criminal courts include Saddam Hussein, while others such as Sudan's Omar Bashir are indicted at the International Criminal Court. Former Nigerian President Olesugun Obassanjo recently criticized Egypt for commencing local criminal proceedings against its non-democratic, former president Hosni Mubarak. Now others like him can hardly be blamed for clinging onto power in order to avoid similar humiliation. Hence Kenya’s notorious Ocampo six desperately seek re-election.

Clearly, if criminal proceedings and retribution are inappropriate to address politically or economically systemic catastrophes like destandarization of labour under globalization in Britain, then military intervention followed by possible prosecution must also be wrong elsewhere. The 1948 UN Declaration of Human Rights recognizes the right of every human being to claim protection against the state. Yet that instrument is neither “universal” nor are its rights “inalienable.”

From the outset its rights mischievously fail to declare the entitlements to opportunities and resources as equal. Legal philosopher Brian Barry argues that it is absurd to assert that that the right to education entails that no one is prohibited from obtaining an education while in reality none but the rich can afford schooling or purchase books. Clearly, the poor who lack facilities also lack opportunities. The right to life is only guaranteed to those who can afford its collateral amenities such as a livelihood in a capitalist society. Without the means to earn a living, the opportunity to live is curtailed. Social equality for the disadvantaged groups requires conferring positive rights such as constructing ramps and lifts to facilitate access by physically challenged persons to spaces in highrise buildings. Formal equality to individuals to enter into five star hotels does not facilitate access by the poor, courtesy of economic discrimination. Since developing countries lack the means to provide for the basic needs of their populations such as food, shelter, clothes, education and even jobs, it is for affluent countries to assume a humanitarian duty to supply such basic provisions.

The current global financial crisis impacts unequally on the North and South. Yet neither UK Premier Cameron nor even US President Barrack Obama do more than subsidize failing companies in their own populations while creating “moral panics” against dangerous minorities at home and abroad. It is essential for human rights lobby groups and even local consumer organizations in Africa apply even-handed standards to determine their definitions of human rights, which inspires an agenda of protest against rising commodity prices. Social justice interests demand that if popular protests are valid in Africa then they are then they can also be used to democratize or destabilize UK. NATO should refrain from bombing Libya while authorizing strongman tactics of using necessary force to suppress popular unrest at home.

In reality, labour has become destandardized the world over, courtesy of the electronics revolution. Many employable persons cannot find gainful employment. The state is not only prolonging the length of compulsory education but also forcing many others to retire early through redundancies termed “golden handshakes.” Computers have driven employees away from car factories in the North and farms in the South. Upon closure of manufacturing industries, purchasing power for agricultural commodities dwindles. Only those with oil can hike the price. The rest succumb to poverty. Yet Beck describes wage labour and occupation as the axis of living in the Industrial society.

Work provides income, status and supports dependants. As work and non-work have become indistinguishable, employers are out-sourcing their jobs through performance contracts. Such part-time or seasonal work is merely contracts for services. It does not provide any medical benefits, retirement benefits, social security or housing allowance, overtime, leave pay. Many employers are under-paying despite large increased profits reaped by multinationals and increased tax revenues paid to the state reflected in the so-called GDP and budgetary expenditure. The masses have no disposable incomes. Women and youth replace men in the workforce since their starting wages are often less. Employers then ruthlessly eliminate personnel to keep pace with cutthroat competition. In Kenya no labour inspectors patrol or criminalize such practices or enforce minimum wage requirements such as the recent one-hundred dollar per month wage guideline for maids.

Without social protection, poverty is a constant companion. Stalked by hunger and bitten by the anger of betrayed promises, the unemployed and underemployed populations of the world must either ritualize, retreat or rebel against the status quo. Trade unions have acquired a so-called right to collectively bargain (Article 41) or even strike under Act 37 of the new Kenyan Constitution. But this is non-existent for casual workers who are non-unionisable.

The gap between the rich and poor is widening intolerably. Poor people want some action. Freedom demands that the 21st century states should not only enshrine a legally guaranteed right to work but also a minimum basic pay. Who should pay to make such rights viable? Why, the affluent populations, of course!

By Charles A. Khamala.

The author is Lecturer at Kabarak University, School of Law; Ph.D. Candidate in Law (Université de Pau et des Pays de l’Adour); Advocate.