Oyster Shellfish: Africa's Untapped Food Security?

|

Unlike all other forms of aquaculture, farmed shellfish have been identified as the only sustainable form of aquaculture that has no negative impact on the environment. Rather, shellfish aquaculture operations actually improve water quality by filtering out pollutants, sediments, and phytoplankton from the water column. Moreover, shellfish are environmentally sustainable since they neither require fish feeds, compete with wild species for food, nor consume more protein than they produce.

Oyster shellfish were once the global ecosystem engineers enabling prosperous habitats for other species. Amazingly, a single adult oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water each day removing nitrogen and other nutrients from the water for mitigating eutrophication and helping control and prevent harmful algal blooms.

Nutritional oysters are the number one farmed aquatic species worldwide packing huge amounts of protein, loaded with vitamins, stocked with omega-3 fatty acids and replete with minerals: calcium, iodine, iron, potassium, copper, sodium, zinc, phosphorous, manganese and sulfur.

The Mighty Pacific Oyster

While Pacific oysters (Crassostrea gigas) originate from Japan, this species has been intentionally introduced in many areas of the world to replace native oysters that have been decimated by disease. Pacific oysters are typically more resistant to the diseases that afflict native oysters and their relatively fast growth rate and high meat yield makes them ideal for farming. Globally, Pacific oysters have become the gold standard for replacing stocks of indigenous oysters severely depleted by over-fishing or disease, and to create an industry where none previously existed.

|

On the West Coast of Africa, the hardy Pacific oyster species has not been recorded north of Namibia; yet it can survive at salinities between 10 and 35 percent and has a broad temperature tolerance ranging between 28 to 95 degrees Fahrenheit. Offshore surface water temperatures for West Africa range from 56 to 82 degrees based upon 25 years of data. By extrapolating temperature data with the scientific certainty that oysters grow faster in warmer water, the Pacific oyster could anecdotally reach harvestable size within 6 months throughout the region. This is because oysters are “cold-blooded” so their metabolic rate increases with temperature, which translates into faster growth rates.

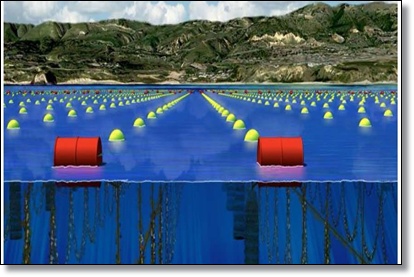

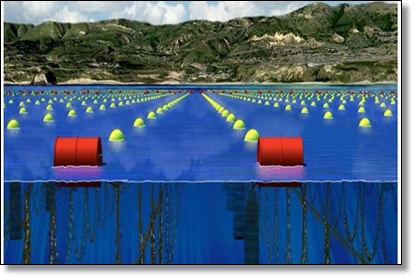

Potential for Open Ocean Oyster Farming in West Africa

A feature article published in the July, 2011 issue of Intrafish, Lifting the Veil on Africa – Aquaculture’s Next Frontier, reported: “Africa has all the characteristics needed to turn itself into an aquaculture force to be reckoned with. Just to maintain the present per capita consumption of fish in Africa, aquaculture will have to expand by 250 percent in the coming years.”

Only by moving aquaculture offshore will this enormous demand for fish be met for helping feed West Africans in the future. Near-shore production has limited capacity for growth due to competition for space and uncertain water quality. Offshore shellfish farms have shown higher growth rates, better meat yields, and heavier production compared with inshore farms. This is attributed to the lower stress, reduced turbidity and better water exchange experienced at the offshore farms.

While commercial shellfish cultivation is currently non-existent in West Africa, there are lessons to be learned from the 2010 report published in the Journal of Shellfish Research “The History and Status of Oyster Exploitation and Culture in South Africa”: After years of experimental trials, South Africa now follows the global trend of importing the much hardier Pacific oyster because there was insufficient knowledge on culturing indigenous species. The introduced Pacific oyster is now widely farmed and has become naturalized in estuaries along the southwestern coast. Approximately 2 million Pacific oysters were annually produced in South Africa throughout the 1970s and early 80s increasing to about 8 million in 1991. The market for cultivated oysters in South Africa has grown steadily during the past decade but production has not kept up with demand.

Introducing the Fittest for Feeding West Africa

The Pacific oyster with its large size, vitality, resilience to adverse conditions, resistance to deceases, rapid growth and reproductive capacity has been a tremendous success for cultivation making it the most widely farmed oyster species in the world. However, the introduction of a stronger foreign oyster has critics claiming harmful environmental impacts because it overtakes the weaker native species.

In a recent New York Times opinion piece, Mother Nature’s Melting Pot, author and anthropologist Hugh Raffles articulately spins the controversial invasive species issue as having positive potential:

“But just as America is a nation built by waves of immigrants, our natural landscape is a shifting mosaic of plant and animal life. Like humans, plants and animals travel, often in ways beyond our knowledge and control. They arrive unannounced, encounter unfamiliar conditions and proceed to remake each other and their surroundings. Designating some as native and others as alien denies this ecological and genetic dynamism. It draws an arbitrary historical line based as much on aesthetics, morality and politics as on science, a line that creates a mythic time of purity before places were polluted by interlopers. What’s more, many of the species we now think of as natives may not be especially well suited to being here. They might be, in an ecological sense, temporary residents, no matter how permanent they seem to us.”

Invasive species in many cases do better biologically in their newly adopted domains, which translates into economic gains for farmers and lower food prices for denizens. Consider:

• Honeybees introduced from Europe in the 15th Century have succeeded in becoming indispensible to agricultural economies across the globe and the more productive farmers are grateful they arrived.

• Tilapia, native to Egypt’s Nile River, easily adapted across the globe to double production during that past decade to about 3.7 million tons with Asia representing about three quarter of world tilapia production. Tilapia’s introduction to Sub-Sahara Africa resulted in a 100 percent increase in production during the past decade, contributing 430,000 tons to food security for the region in 2010.

• Soybeans, native to China, now represent a $30 billion industry in the United States; ironically, over half of the world’s soybean exports now go to China where the crop originated.

West Africa has over 300 million people and its population is expected to double in 20 to 25 years at the present rate of growth. A new open ocean farming paradigm introducing the Pacific oyster as the “soybean of the sea” for a "Blue Food Revolution" should be given serious consideration. As traditional fisheries collapse, this could become a sustainable solution contributing to food security for the region.

By Phil Cruver, President.