The Pope and Africa’s Witchcraft Menace

|

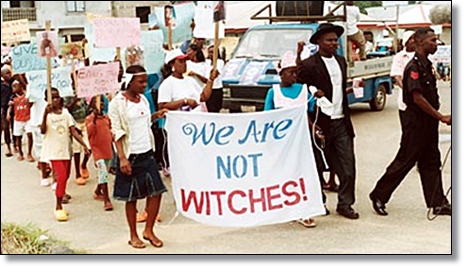

| Children in Nigeria decry the witch stigma Photo courtesy |

The eerie image of a one-month-old baby called Mercy accused of being a witch and afterward abandoned to die in Ghana’s Upper East Region reminds me of the beginning of the Book of Job, where in the mysteries of evil, God and Satan talk to each other about how much pain Job should go through before he caves in. Baby Mercy is no Biblical Job. She is too young to know what is wrong and right and why she should go through pain and death.

Baby Mercy’s ordeal is set in a Ghanaian culture which believes in witchcraft as the cause of existential adversities. She was dumped in a dark room to die and go away with her alleged evil. Baby Mercy did die.

Like most parts of witchcraft-infested Africa, baby Mercy’s inhuman ordeal is going international in an attempt to find solutions to Africa’s ancient witchcraft calamity that have been entangling Africa’s progress. In some parts of Africa, the witchcraft hazard is so deadly that it has made people live almost permanent impoverished lives and terribly consumed in perpetual ignorance, fear, and misery.

In this African witchcraft universe, every existential challenge – death, hunger, accidents, disease, conflict and poverty, among others, are attributed to witchcraft. There is no human agency responsible for glitches. Witchcraft is responsible for all problems. Witchcraft beliefs are so dominant that they decide the African’s fortune, asphyxiate him and renders him helpless. How bizarre and troubling!

Roman Catholic Pope Benedict XVI, in Benin Republic recently, warned of the dangers of witchcraft to Africa’s progress. The Pope imbues the Ghanaian enlightenment movement with a strong recommendation and a degree of validity. The Pope said Africans “must fight against dangerous beliefs and superstitions.” Materially, the African reality is that witchcraft is counter-productive to Africa’s advancement. Witchcraft beliefs simultaneously undermine Africa’s civilization and make the African uncivilized and self-destructive.

In African’s witchcraft universe, the African lives in eternal anxiety. This makes the African life pathetic. The consequences is the booming spiritual churches, juju and marabou spiritual mediums and witchdoctors who allegedly work spiritually to ward off supposed evil spirits, witches and other malevolent forces that allegedly afflict Africans. Such activities have also inflamed the witchcraft craze.

Though not openly accepted, witchcraft is a pandemic in Africa, impinging even on African elites’ thinking. After fifty years of self-rule, African leaders have not demonstrated any grasp of the connection between witchcraft and progress, and strategize solutions to tackle the contagion. Witchcraft is a psycho-cultural disease. Witchcraft’s main victims are children, older folks and generally defenseless people. UNICEF, the global children’s welfare agency, says tens of thousands of children in Africa, like Ghana’s baby Mercy, are tortured and killed because of witchcraft.

The social disease of witchcraft is prominently seen in the vast Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Underlying DRC’s recurring misery is the strong irrational believe in witchcraft. Witchcraft has entangled the reasoning of the DRC so much so that even when a refrigerator breaks down, families blame their children for bewitching the refrigerator. Some children are killed and some cast away as a result.

African leaders aren’t immune from the witchcraft poison. Equatorial Guinea’s President Francisco Macias Nguema tough witchcraft practices were projected nationally in devastating fashion. Macias used the knowledge of witchcraft he inherited from his sorcerer father and built a huge collection of human skulls (from the people he has killed for his witchcraft rituals) at his homestead. Marcias used witchcraft to engage in human sacrifice, including burying some of his victims alive with juju-witchcraft rituals. Marcia darkened Equatorial Guinea as a result. Despite Marcias’ subsequent death by firing squad, witchcraft is still problematic in Equatorial Guinea.

The troubling African witchcraft menace is at the centre of the African human stories, as Pope Benedict XVI indicated in Benin. Witchcraft has become a “social drama.” In poor African families or those affected by life’s tragedies, often, the witchcraft culprit is hunted out in those who are weakest, who are then are tortured, killed or cast away. A few months ago, a 72-year old woman was accused of being a witch and burnt to death in Ghana’s port city of Tema. The witches’ villages, where those accused of witchcraft are protected, in Ghana’s northern regions reveal the complexity of the witchcraft syndrome.

The British philosopher and poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge would say, witchcraft “has its ground or origin in the agent, and not in the compulsion of circumstances.” In Africa’s witchcraft practices, there isn’t any compulsion of circumstances – the destruction of the witchcraft victim is driven by the sense that witchcraft rather is responsible for life’s existential troubles and not the African accountable for his or her actions. That’s where we draw the Coleridge line.

Such thinking makes the African appear intellectually fragile and at the mercy of external forces that cannot be rationalized. Nature is far out of this equation. Rather, the African is nurtured into such inexplicable witchcraft beliefs by certain parts of the African culture. It feeds into the African’s strong believes in evil spirits, demons, witches, juju and other malevolent forces as responsible for life’s difficulties. The African isn’t accountable for his or her actions.

Such predicaments reveal the battle between rationality/human agency and irrationality in the soul of the African. The African appears helpless under this bizarre battle. There are two possibilities: 1. The believer in witchcraft does not question why witchcraft is responsible for life’s tribulations. 2. The witchcraft believer acts under not only the cultural circumstances but also his or her human agency. In such frame of mind, the witchcraft believer is guilty of atrocities committed against victims of witchcraft accusation and not witches influencing circumstances.

At Tete, a village in central Mozambique, there is an alarming rise in witchcraft accusations. In June this year, Simon Manuel Gomes’s hut was burned down by his son. All of Gomes’s property was destroyed and he narrowly escaped death. This happened after his son had visited a traditional witch doctor, who told him his sexual impotence was caused by being bewitched by his father.

Despite African elites’ long silence on Africa’s witchcraft peril, witchcraft is a psychological pandemic that has to be tackled head on if the African is to live a comfortable life. Unlike the unrealistic African elites, Pope Benedict XVI and his mission have pondered about Africa’s witchcraft plague. The Pope’s solution: “Being a regional problem, a joint effort of the ecclesial community would be important to counter this calamity, trying to determine the deep meanings of these practices, to identify the risks for pastoral and social development, and to find a method leading to its definitive eradication, with the cooperation of governments and civil society.”