Crossing Borders: Women Informal Traders Capture City Spaces

Talking to The African Executive, Dr Mary Kinyanjui of University of Nairobi’s Institute of Development Studies observes that in too many places, it is still too difficult for a woman to start a business. Cultural traditions may discourage her from handling money or managing employees. Complex regulations may make it hard for her to buy land or keep land or get a loan. Using women informal business owners at Taveta Road in Nairobi, she argues that future economic growth in Africa depends on tapping the entrepreneurial skills of women. African women ought to get the tools and the resources they need to produce, market, and sell their products.

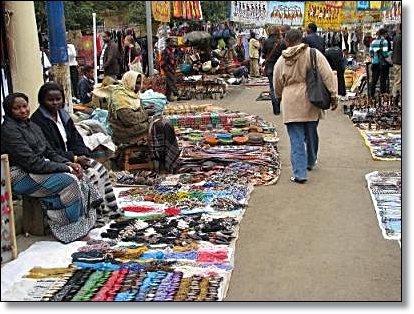

Women traders Photo courtesy

Q. Briefly describe Nairobi city space during the colonial era and shortly after colonialism.

During the colonial period, Nairobi city was segregated on the basis of race. While Europeans occupied the most accessible parts of the city, Asians occupied the middle spaces while Africans occupied the outskirts. After independence, city buildings that were previously owned by white people were acquired by rich Kenyans, majority who were men. Ordinary Kenyans squatted on empty plots, roadsides or undeveloped land.

Q. How did women who were largely excluded from the city’s spatial policies eventually acquire trading spaces in the heart of the city?

The process involved ‘take- off’ (that saw elite businesses withdraw from urban spaces due to liabilities in business) and ‘takeover’ that saw subalterns occupy and make territorial claims in spaces formerly occupied by elite businesses, among other factors.

I will use the “Taveta Road” phenomenon to explain this. Taveta Road has five buildings which are all occupied by women. In the 1990s, most buildings on Taveta Road housed Asian-owned retail shops. The liberalization of the housing market in the city led to the rising costs of buildings and premises. As the cost of buildings in the city doubled or tripled, it became difficult for an individual to hire out a building and make profit. As Asians began to close shops within the city due to the increased costs of rental buildings, women began to jointly ‘take-over’ and rent the shops that Asians had ‘taken-off’ from. They would subdivide the shops into stalls, thus lowering the cost of doing business. Some prominent businessmen and women also rented the shops, subdivided them into stalls and rented them out to small scale vendors.

The liberalization of trade and opening up of new markets for imported goods from China, Dubai, Turkey and South Africa also contributed to this acquisition. Travel to these countries was easier compared to Europe and North America which had stringent visa regulations. Although, liberalization led to closure of businesses, it opened up avenues for new traders who could travel abroad in groups. Upon return, the groups would sell their goods in exhibitions. Initially, customers would pay to enter these exhibitions but this was withdrawn. The stiff competition that Asian goods faced from imported goods made some of them to wind up their businesses. Women then took over.

Another factor was the act by a man called Nelson Kajuma constructing temporary stalls on sites that he leased from the city council. He would rent the stalls out to individuals to carry out small businesses. Individuals who sold goods in these stalls were not harassed by the city council. When other hawkers quickly realized that one did not need a large space to sell goods, but could be housed in a small cubicle and operate without harassment, they joined the bandwagon. Among them were women traders. This gave them a sense of entitlement to owning business space. Women feminized Kajuma’s concept and looked for buildings in the city to subdivide into small business spaces; hire out and occupy. Today, a good number of regular shops on Moi Avenue, Tom Mboya Street, Latema Road and Taveta Road have been converted into small cubicles for trade in clothing and electronics.

The ability for women to organize themselves into chamas (welfare groups) where they would pool money and give to one person on a rotational basis to buy durable goods, invest in business or invest in microfinance greatly helped them acquire trading spaces within the city. When the stalls opened up, they were able to get loans from the group savings as collateral and members as guarantors. The women would then send one of their group members to purchase goods abroad on behalf of the rest. Through collective action, women learnt from each other and contributed to the construction of alternative business spaces.

Trust was also a key factor. At the time of entry, some women already knew each other. Home visits and sharing of meals had bonded them and increased their trust in each other. That is why a group could comfortably send one of its members to Turkey or Tanzania to buy commodities on behalf of the rest. The trust was further enhanced by the fact that each person in the cluster had a reference point who brought or introduced her to the cluster, and thus could be traced. The trust enabled them to stay in the ship as well as draw positive energy from each other.

Q. What are the implications of women agency?

By feminizing the Kanjuma concept, the women have brought the ordinary to the city. This ordinariness includes occupying shared spaces like in a typical African open-air market or operating in small cubicles. Women have contributed to the transformation of the cityscape in Taveta Road and other parts of the city. The women’s self-organizing into chamas that pursue social justice confirms the importance of social infrastructure in contemporary African cities. It largely points to the fact that African cities are driven forward by the rubric of social networks.

It also has implications for the feminist theory. African Women are proactive unlike in the feminist theory where they are presented as victims or subordinates to dominant cultures. The informal economy women exhibit a form of subaltern feminism that is different from the elite African women feminism which is mired with foreign ideologies.

The phenomenon also has implication for the post capitalist theory. The women have contributed to the emergence of a community economy in the city where competing individuals co-share premises, create economies of agglomeration but still compete.

The women’s prior self-organization largely points to the need for giving people space and opportunity to evolve their own initiatives. Such initiatives can become congruent with the larger macro social and economic changes taking place nationally.

Q. The mounting acknowledgement of women contribution has not translated into significantly improved access to resources and decision-making powers. What should they do?

Women have to be increasingly proactive; organize; express their concerns at both grassroots and national levels and seize opportunities created by the new political openings.

Q. What should African governments do?

Governments' macroeconomic policies ought to incorporate gender perspectives in their design as improvements in women's incomes can significantly promote equity in their respective communities. Gender prejudices negatively impact on women's access to productive resources and markets, ultimately frustrating economic reform policies. Since women informal traders have not passively sat and waited for government or donor largesse to catapult them to socio-economic wellbeing, it makes economic sense to take into account gender biases and tailor planned interventions to improve women's ability to take advantage of incentives, thus enhancing overall socio-economic efficiency. As Secretary of State Hillary Clinton once said during the African Growth and Opportunity Forum in Zambia in 2011, "No country can thrive when half its people are left behind." And the evidence is persuasive: women agency is a major driver of economic growth.