Planning for Inclusive Growth in Africa

|

Africa is the least urbanised region with low average population densities; long distances within countries and between African countries and their trading partners; as well as too many borders which fragment the continent. It is estimated that as many as a third of Africans live in landlocked countries. What does the persistence of these conditions after more than half a century since independence in many countries say about our progress?

To take Africa forward, we need a different political perspective and planners who appreciate the enormous burden they bear of physically transforming their societies. Planners need to be cognisant of the challenges that lie ahead. Around half the world’s population is already living in cities and the number looks set to rise. In South Africa we estimate that 8 million more people will live in cities by 2030. The economic and health imperative to plan for and create sustainable cities is not a luxury; it is a necessity if the 21st century is to provide a secure and sustainable way of life for a world population that over the next four decades will increase by a third.

Cities are central in bringing about tomorrow’s ‘green’ economic benefits and welfare; the provision of decent jobs and human well-being within an environment liberated from the risks and threats of climate change, pollution, resource depletion and ecosystem degradation. The quest for sustainability will be increasingly won or lost in our urban areas. The promise that the cities hold requires foresight, political will and intelligent planning.

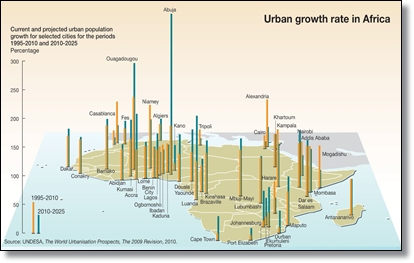

Over the next three to five decades, Africa will experience unprecedented levels of urbanisation. Whether or not this delivers benefits for the people of Africa depends on whether the profession of planners is able to rise to the challenge. It also depends on whether political decision makers create the necessary policies to enable planners to make the right planning decisions.

The report of the Africa Progress Panel (African Progress Report 2012) notes that “Africa in 2012 has an unprecedented opportunity to set a course for sustained economic growth, shared prosperity and a breakthrough in poverty reduction. But this journey will not happen without determined action and crucial changes to make growth much more equitable”.

It carries a strong message for policymakers to focus on jobs, justice and equity to ensure sustainable, shared growth that benefits all Africans. It further warns that failure to generate equitable growth could result in “a demographic disaster marked by rising levels of youth unemployment, social dislocation and hunger.”

The future of the global economy, including African economies will be driven by many factors – some global, some specific to particular countries, some known and others unknown as yet. Five key known global factors that will shape the world and Africa are noted in the Africa Progress Report 2012. They are:

• Demography and human geography. African cities will need to prepare for a youth surge as well as increasing urbanisation. It is estimated that Africa’s youth population (15 – 24) will increase from 133 million at the start of the century to 246 million by 2020.

• Global food security. The fast growing world population, global warming and climate change will put immense pressure on agriculture and compromise food production.

• ‘Tectonic’ shifts in economics and politics. The rise of emerging powers creates wider conditions for growth in Africa, but also requires management of integration with emerging markets. The tilt in the geopolitical centre of gravity from West to East will have profound implications for the world economy. China has become an especially dominant force in the global economy. In 2010, it outstripped Japan to become the world's second largest economy as measured in nominal GDP (about 40 percent as big as the United States economy), and was by far the biggest contributor to global GDP growth; its economy added US$638 billion to growth in global nominal GDP, versus US$497 billion added by the United States economy. By some forecasts, China will overtake the United States as the largest economy by 2025; others put the date at 2035, or even 2050.

• Science, technology and innovation will fuel growth and development - highlighting the importance of an African agenda for science, technology and innovation, as well as the importance of ICT connectivity.

• The rising tide of citizen action and global social protest - fuelled by the availability of communications, technology has opened up new forms of organisation and helped citizens regain their voice.

• In addition to the forces identified by the African Progress Panel, I add the demand for Africa’s mineral resources. Examples abound of how the natural resources are again redefining Africa’s relationship with the rest of the world. Consider for a moment how the city of Luanda has changed inexorably as a consequence of infrastructure development by the Chinese.

These factors are not dissimilar to those identified in the National Development Plan. If these shaping forces are unsettling for a profession that for the most part sets and administers rules, I hope it convinces us that we cannot rely on yesterday’s tools to solve today’s problems. Tomorrow’s challenges will undoubtedly be far more complex and will require different approaches and tools.

There are actions we can take today to prevent tomorrow from being catastrophic. The African continent faces significant deficits in infrastructure, entrepreneurship, human resources, science and technology. The experience of the last decade shows that with consistent and focussed leadership, we can make significant progress as Africans. During the last decade the African continent experienced improvements in macroeconomic management and governance. Africa has also witnessed a substantial improvement in economic performance, with average GDP growth of 5.6% between 2002 and 2008, making Africa the second-fastest growing continent in the world at times. This growth was not limited to resource-rich countries.

Africa also recovered much faster from the economic crisis than many other continents. In order to sustain growth, African governments need to continue to promote good governance, make the most of the demographic potential of its youthful population and prepare for increased rates of urbanisation. Industrialisation and investment in infrastructure and human capital is also critical. However, simply identifying priorities for the development of the continent and stating what needs to be done is not enough.

Creating more equitable, inclusive societies in Africa has to top our development agenda. Achieving it requires complex interventions at multiple scales - ranging from regional, national, sub-national, city and neighbourhood scale. Political decision-makers need to create space for planning norms and standards, failing which those with spending powers will do as they please, and the people of Africa will remain poor.

Urban practitioners around the world convened in Naples, in Italy for the World Urban Forum, where the State of World Cities 2012/2013 was launched. Under the title, “The Prosperity of Cities” the report calls for development actors to shift attention around the world towards a more robust notion of development that looks beyond economic growth and include various dimensions. The five dimensions of prosperity it proposes include productivity, infrastructure, quality of life, equity and environmental sustainability.

The State of the World Cities report recognises that the world is engulfed by waves of financial, economic, environmental, social and political crises. It also recognises that an over-emphasis on purely financial prosperity has led to growing inequalities between rich and poor, generated serious distortions in the form and functionality of cities and caused serious damage to the environment. Planners have the mammoth task of directing development in ways that help overcome these distortions and secure a prosperous future for people of the globe.

Turning to the National Development Plan. Two years ago, we began the difficult but necessary work of planning for a prosperous future. We drew on enormous amounts of research that existed already in various sectors. We also benefited from the insights of those who have been involved in planning in this country for many years. The plan that we produced does not purport to be policy. It harvests existing policies and packages them in a way that enables better implementation.

In the plan we outline six pillars that we believe are necessary preconditions for fighting poverty and inequality. They are to:

• Unite South Africans of all races and classes around a common programme;

• Involve all citizens actively in their own development, to ensure that democracy is strengthened and government held accountable;

• Raise economic growth, promote exports and ensure that the economy is more labour absorbing;

• Focus on the key capabilities of both people and the country. (We interpret the idea of capabilities to include health, skills, infrastructure, social security, strong institutions and partnerships)

• Build a capable and developmental state; and

• Ensure strong leadership throughout society to work together to solve problems.

The diagnostic overview released in June last year identified the pervasive spatial challenges as one of the reasons for trapping and marginalising the poor. Our settlement patterns place a disproportionate financial burden on the poorest members of society. These patterns increase the cost of getting to or searching for work, lengthens commute times, raises the costs of moving goods to consumers. The ripple effect of this is felt throughout the economy.

The plan commits an entire chapter (8) to transforming human settlements and the national space economy. It calls for a systematic response to entrenched spatial patterns that exacerbate social inequality and economic inefficiency.

The proposals are structured according to three main themes, namely strengthening our vision for human settlements, improving implementation instruments and building capabilities – not only in the planning profession, but also in communities. Some of the specific objectives outlined in the chapter include:

• Strong and efficient spatial planning system that is well integrated across the different spheres of government.

• Upgrading all informal settlements on suitable, well located land by 2030.

• More people living closer to their places of work.

• Better quality public transport.

• More jobs in or close to dense, urban townships.

Some of the immediate actions necessary to achieve these spatial objectives are:

1. Targeted reforms to the spatial planning system for improved coordination.

2. Developing strategies for the densification of cities and resource allocation to promote better located housing and settlements.

3. Substantial investment to ensure safe, reliable and affordable public transport.

4. Spatial development frameworks and norms, including improving the balance between location of jobs and people.

5. Comprehensive review of the grant and subsidy regime for housing with a view to ensure diversity in product and finance options that would allow for more household choice and greater spatial mix and flexibility. This should include a focused strategy on the housing gap market, involving banks, subsidies and employer housing schemes.

6. Establishment of a national spatial restructuring fund, integrating currently defused funding.

7. Creation of national observatory for spatial data and analysis.

8. Creating incentives for citizen activity for local planning and development of spatial compacts.

9. Mechanisms that would make land markets work more effectively for the poor and support rural and urban livelihoods.

One of the fundamental questions that we should always retain at the back of our minds is how change happens in society. As a still-young democracy, we have the privilege of sharing ownership of the truly empowering Constitution. I occasionally hear people ascribing the tardiness of transformation to the Constitution; respectfully I submit that they are wrong. The Constitution empowers and enables, but beyond that actual change requires human actions. So, for transformation it is important that we recognise the value of our Constitution as presenting the values that bind and enable us.

A second aspect of change that we sometimes appear to aimlessly debate is the place of policy. Policy should guide and provide a framework for evaluating the progress of actions by people. Policy documents do not suddenly assume the ability to walk, talk and act – they only guide. In guiding it is also important that we recognise how different policy elements intersect and mutually reinforce.

A third aspect of transformation is about who is responsible. The short answer may be that it is and remains the exclusive domain of government. Again, we will counter that this is patently untrue. Whilst government should never be allowed to devolve its responsibility, the process is actually a bit more complex. The Commission is of the view that transformation occurs when a number of agencies interact. The first, and perhaps the most important of these is an active citizenry – a nation whose conscience is vested in the ordinary women and men who comprise and who act in their own and in the national interest – they cannot outsource this responsibility to government. The second agency is leadership – focused, determined and manifest. When we speak of leadership, we counter the notion of the “big man.” Our model of leadership is one that involves tens of thousands of active citizens who take initiative, in the common interest. The third agency is an effective government. This needs to be a clear objective at local, provincial and national levels. An effective government is responsive to the needs of its people, in its listening, policy priorities and allocation of resources. Without the close interaction of these three agencies, no transformation is possible.

Conclusion

Turning visions and plans into reality is hard work. It requires us grappling each day with two questions posed by Ben Okri," can we make something worthwhile of our freedom? Can we create a good life for our people?" Engaging with these questions starts with understanding the reality that wrong does not self-correct, transformation only happens when leaders engage in the messy day-to-day reality of implementation. It requires the marshalling of human and financial resources; investment in the development of skills of planners among others; and creating incentives for young people to choose the planning profession. It requires the strengthening of the capacity of governance in planning – ensuring that government (at whatever sphere) is focused on norms and standards and not permit developers to over-ride. We should also look at compliance and enforcement through different lenses – simply issuing penalties is hardly sufficient. We need a compact between developers to ensure that all parties work towards the same goals.

The loops in local government democracy need to be closed. Very often planners visit communities with councillors to elicit views but seldom return with responses. This breeds mistrust.

Finally, in every society there are always more needs than there are resources. Planning is about making choices and prioritising between competing demands.

By Trevor A Manuel

Minister in The Presidency: National Planning Commission,

Republic of South Africa.