Somalia: The Road for Post-Transitional Government

|

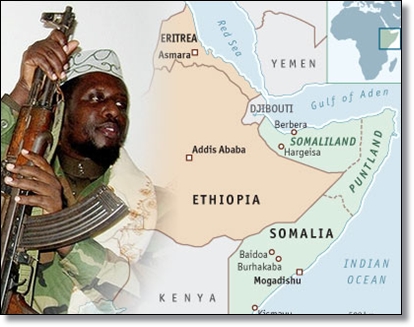

| Somalia braces to stand on its own feet Photo courtesy |

Basically, the new post-transitional government is responsible, with help of international partners, for its state and security. Already, Somali forces together with coalition partners are taking over key towns from the insurgents, notably Kismayo, the third largest city in Somalia and al-Shabaab's biggest revenue-generating town and ramping up their operations. In addition, the aim for post-transitional government is, in essence, to let Somalia to stand on its own – politically and militarily – and have four years mandate to structure and lay the groundwork for a prosperous Somalia. Moving forward, the African Union has formally proposed to the UN to lift the arms embargo on Somalia, to enable the new government establish its own security.

Hassan Sheikh Mohamud represents the new crop of leaders who are genuine and seek to resuscitate Somalia. His appointment itself was a rare moment for Somalia; unlike previous governments where the presidents and parliamentarians were cooked outside and parachuted on the ground, he was appointed inside the country – Mogadishu – and enjoyed a degree of legitimacy. This new political momentum would not have been possible without the courage of the previous transitional government who, despite all its setbacks, paved the way for responsible transition. Of equal importance was the international community's unflagging commitment in ending the roadmap process that yielded this nascent transformation.

But looking ahead, and as the dest begins to settle slowly, the prospect for successful transition is in the offing – at least in the foreseeable future. Some fundamental facts remain unchanged; government institutions are woefully dysfunctional, insecurity has reached into unacceptable level, Somali forces heavily dependent on AMISOM 's assistance in every step of the way, the government is in bankrupt. As yet, and despite al-Shabaab been severely degraded, they still remain very potent force and control a sizable swath of territory in the central part of the country, the country finds under sway of competing – yet at odds – foreign powers. Addressing these challenges will not be easy, but keeping them in mind will help the president to avoid repeating past mistakes.

Chronic Insecurity

First and most important is the security. In the days leading to the presidential election, countless people have been killed including seven journalists, politicians and district commissioners, showing how security situation remains very tenuous. Moreover, al-Shabaab are hiding among the local people, intimidating and killing journalists and government officials. Their assassinations, hit-and-run tactic – sort of asymmetrical guerrilla warfare, remain a lethal threat to local population. The new government, for its part, must encourage local residents to tip-off suspicions, enforce the local government systems. The last government, for its credit, have fairly managed on this and collaborated with local population to ensure community-centered security. This is very important measure to enhance local security. For years, challenges have been tackling the widespread insecurity, which is the biggest source of instability in Somalia.

Most dangerously, a recent report by the Saferworld – a UK based think-tank, found that an staggering number of Somali police work for private companies and individuals largely due to the the government's inability to pay their salaries. Rebuilding Somali national security forces entails a concert steps and shaped with realistic plan. The president must improve the quality, the morale, of Somali army and police, reimburse their overdue salaries and strengthen central and regional administrations. Ultimately, Somali national and cohesive army can secure and stabilize the country.

Governance Institutions

Another unrelenting obstacle for the government lies in the weak government institutions. Over the past decade, there have been numerous transitional governments that were paralyzed by infightings and run a government without institutions. The only exception to this is the National Security Intelligence who prop up by other Western intelligence agencies but performed reasonably well to push the insurgents at bay. Rightly or wrongly, previous governments were widely regarded as syndicate corrupted officials who put their interest first, and second the country. At this point, Somalia lacks functional government institutions that is capable of delivering basic services including health, education, water and all social infrastructures. The new government must plan to address these crippling government institutions who feed instability, extremism and poverty.

Than come to Kismayo, by far the most complex issue of the day in Somalia. Obviously, the fall of Kismayo has dealt a huge blow to al-Shabaab's marginalization but its is harbinger to more sinister things to come: the intensification of deep-seated inter-ethnic rifts. Historically, Kismayo has been a multi-ethnic region with no specific clan configuration. Its very complex place where local realities often diverse. Secondly, while the coalition troops have successful toppled al-Shabaab, the real test is now weather they will succeed in building effective local governance system – some kind of tribal local structure, that fills the vacuum and provides the basic services to the local people. Thirdly, and perhaps more dangerously, its the long-established regional rivalries between Kenya and Ethiopia over Nairobi's driven Jubbaland Initiative, which is problematic on many level.

Therefore, in the grand scheme of things, the debacle of Kismayo will only intensify the regional rivalries – through directly or by proxy –, to the detriment of the new government. Fourthly, the role of Mogadishu government has been blatantly undermined, adding fuel to the already deep-rooted suspicion by the Somali government in Kenya's motivation towards Kismayo. To avert future fallout, IGAD, the inter-governmental body's role is very critical to coordinate and provide frameworks for cooperation between the stakeholders.

Talks with Al-Shabaab

Unlike his predecessor, president Hassan has realistic narrative towards negotiating with al-Shabaab. Like he often says, al-Shabaab made up of two camps – nationalist (Somalis) and global Jihadist (foreigns) –, all with their own views of negotiation and peace agreement. There're a considerable elements, mostly a frustrated and disoriented youths, who can be reconcile and pursued. And this is the camp the president wants to bring into the process, and he's right about it. Then, there is small – but quite powerful – global Jihadist inspired hard-core contingent whose vision for Somalia, among other things, is to become a launching pad for terrorist activity and keep Somalia in anarchy for their own benefit and safety. There can be no accommodation room for this camp.

To avoid past mistakes, the president needs to articulate his negotiation strategy package. A blank-check negotiation wont help, the president must appoint an interlocutor or governmental body to spearhead the process.

For its part, international community, while continuing its decapitation figures, should abandon its narrow focus on fighting terrorism to a broader approach of reconciliation and diplomatic engagement by strengthening the government institutions, providing resources and support for the national reconciliation project.

External Players

Even if Somalis agrees on broad-based internal political settlement, the country still needs a broad-based external political settlement as well. This where the international community's role comes to mind. For years, Somalis and non-Somalis alike, have questioned – and critiqued – about the external interferences in Somalia's own affair. Aside from the external elements, Somali leaders are well to blame when they invite external actors to take part and reconcile in their internal disputes. This practice was notorious in the past government. For the sake of their own stability, neighboring countries, Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda and Djibouti need to agree on coherent and constructive strategy for stabilizing the country, one that respects Somalis sovereignty and forswear internal intervention.

The greater international donor community should support, with no strings attached, Somali's plan for stability, governance and developments. At the end of it, the international community's interest in Somalia is to see Somalia become stable, a country that is at peace with itself and to the world. And this should be the ultimate goal for the international community.

The importance of minimizing the foreign intervention was, however, recognized by many including Ken Menkhus, one of Somali's eminent scholar, through a recent Nairobi Forum and contended: “As Somalis are sick and tired of statelessness, perpetuate conflicts, warlordism and piracy they're, equally, sick and tired of us – the international community.”

By Abdihakim Aynte.

The author abdihakim.aynte@gmail.com is an independent analyst.