Somalia: Learning from the Past

|

It’s puzzling that the inter-riverine region, which was once the commercial centers of Somalia, would experience a famine when the region saw less conflict than many other parts of the country. Yet the famine was confined to these areas, with its largest urban area, Baidoa, being dubbed ‘the city of the death.’ By mid-1992 the death toll in Baidoa alone had reached over 200 a day, with relief workers reporting dead bodies littering the streets and some comparing the situation to Auschwitz.

What has caused these repeated famines in the most agriculturally-rich regions in the country? One thing is sure, the famine was not the result of environmental circumstances. Other cities in Somalia, such as Galcaio, were equally affected by the drought and had a similar interior location like Baidoa making it difficult for relief works to reach, yet no famine was experienced there pointing to the man-made nature of this catastrophe. Experts agree that both famines could have been averted.

Food as a weapon

According to Nobel Prize winning economist Amartya Sen, functioning democracies play a role in preventing famines because democratic governments “have to win elections and face public criticism, and have strong incentive to undertake measures to avert famines and other catastrophes.”

Somalis have dealt with bouts of drought through-out their history, but famines were unheard of until recently. Somalia had a short-lived nine-year experience with democracy, but following the military coup d’état in 1969, successive ‘governments’ have used food as a weapon. It first started following the Ogaden War of the late 1970s when the brutal regime of Mohamed Siad Barre was accused of using food aid to enrich political allies and pursing a scorched-earth policy to crush political dissidents (killing livestock, destroying crop and poisoning water-wells), setting an ugly precedent for years to come. The blockage of emergency food aid was responsible for turning both droughts into devastating man-made famines.

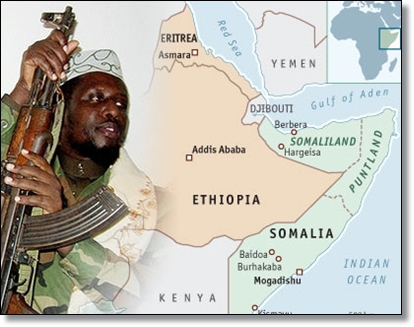

With the ouster of the former dictator, it became increasingly clear that neither faction of the United Somali Congress (the rebel group that was in control of Mogadishu and much of Southern Somalia) was willing to form an inclusive or democratic government. To them, it was a zero-sum game with the winner taking all. With the continuation of the civil war, those without arms were at the mercy of marauding gangs. In the early 1990s, forces loyal to Barre targeted the inter-riverine region with the aim of displacing the inhabitants and occupying their farms. Elders in the region recall militias burning crops, essentially bringing agricultural production in the region to a standstill, and confiscating animals and stored grain.

By 1992, the regions dubbed the ‘triangle of death’ were in the control of militia’s loyal to warlord and self-proclaimed President Mohamed Farah Aidid, who pursued a genocidal policy against the inhabitants of the region and made it difficult for aid workers to reach the surrounding villages. The militias would routinely harass and attack aid workers, obstructing their work to prevent the delivery of food aid to those they saw as their political opponents. Soon enough the clan militias started to realize the value of the food and looters began stealing food aid to sell on the market for cash or would trade them for weapons and ammunition. Unsurprising, nearly two decades later similar tactics were employed by Harakat Al-Shabaab Al-Mujahideen.

The rise of political Islam

By the time the U.N. peacekeeping force had arrived in Mogadishu, the ‘White Pearl of The Indian Ocean’ was an empty shell of what it used to be. The capital lay in ruins and the ‘government’ of Ali Mahdi Mohamed did not provide even the most basic of services. Robert Oakley, the former U.S. Ambassador to Somalia, urged the Somali factions to share power and rebuild the country’s institutions. He feared the alternative would see Somalia headed down a path similar to that of Afghanistan.

The absence of a real government saw the rise of political Islamist movements which would ultimately prove to be one of the most significant developments in post-war Somalia. Starlin Arush, a peace activist who was murdered in 2002, believed that Islamist radicals, who were rumored to be receiving support from Iran and Sudan, benefited from the anarchy just as the clan militias did. In her opinion, they were lying in wait for the right opportunity to pounce and gain power and, less than a decade later, her assertions would be proven to be correct.

Islamist groups began popping up everywhere, but all operated with the blessing and co-operation of the numerous clan militias. In Mogadishu, by April 1991, the first ‘Islamic court’ had been opened by the interim chairman of the U.S.C., Hussein Shidow. In the Medina district of the capital, the courts began enacting a harsh, Wahhabi, interpretation of Sharia law that the Somali people were unaccustomed to. They were known to hand down arbitrary sentences without any right to appeal and carried out capital punishment, amputations and public flogging. They were also in control of the Southern port city of Merca where they used port revenue to buy arms and set up a military training camp. The city would remain in the hands of various Islamist groups until being liberated by the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) forces in August 2012. In the Northeast of the country (present-day Puntland), radical Islamists were in control of the Bosaso port, where they used port revenue to fund their activities. They were eventually defeated and expelled by the Somali Salvation Democratic Front (S.S.D.F.)

By November 1992, between 300,000 to 500,000 Somalis had died of starvation. Despite the increase in media attention, food aid, and supplies, the situation was worsening at a dramatic pace and the death toll continued to mount. It became increasingly clear that no effective solution to the humanitarian crisis could occur without stabilizing the affected regions first.

Upon hearing news of the planned increase in foreign forces, the ‘Somali Islamic Union’ met with General Aidid to unite their forces and form an alliance to fight the U.N. presence in Somalia. They declared a jihad against the ‘infidel forces’ and told their followers that it was obligatory for them to fight UNITAF. One month after Operation Restore Hope had begun several other Islamist organizations established an alliance with Aidid. The Islamists used the foreign forces’ presence to play on nationalistic & anti-colonial feelings and began circulating propaganda against the foreign forces and humanitarian organizations. They claimed that the foreigners were fighting the establishment of Islamic law in Somalia, plundering the country’s natural resources, and forcefully converting Muslims to Christianity – all claims made by Al-Shabaab against AMISOM.

With the arrival of the UNITAF, the attacks against the humanitarian organizations grew more brazen. The militias routinely attacked aid ships and aid workers were harassed and assaulted. As the country slid further into a downward spiral, Al-Qaeda trained foreign jihadist started streaming into the country, the foreign jihadists and Somali militias were all united by a single aim: the forceful expulsion of the UN forces and aid workers. The conflict would culminate in the infamous ‘Black Hawk Down’ incident during the Battle of Mogadishu when U.S. and U.N. forces attempted to capture warlord Mohamed Farah Aidid for his part in the deaths of twenty-four Pakistani peacekeeping troops and the murders of at least 25,000 unarmed civilians.

Withdrawal

After meeting their mandate and ending the famine, saving an estimated 100,000 lives in the process, the United Nations declared their mission a success, ignored the growing Islamist threat, and moved to end their proactive policy in Somalia. By 1995 the U.N. had given up on peacemaking efforts in the country and the last of the U.N. troops departed from Somalia leaving the radical Islamist scourge to be dealt with by AMISOM forces nearly a decade and half later.

The withdrawal of U.N. troops played right into the hands of the terrorists. With no legitimate power or government to challenge them, the Islamist strengthened their presence in the country and continued to fester unabated. By mid-1998, Al-Qaeda operatives who were active in Somalia went on to launch attacks on the U.S. embassies in Tanzania and Kenya.

By then, many Somalis had given up on depending on a national government to ensure security in their regions. The Northeastern regions (Puntland) would go on to establish a semi-autonomous state and the Northwest regions (Somaliland) declared independence from Somalia. With the failure of consecutive reconciliation conferences, more and more regions began assembling to restore peace and governance in their respective areas.

A few short years later, self-styled ‘moderate’ Islamists had their first (of many) political victory with the ‘election’ of Abdiqasim Salad Hassan as the President of the Transitional National Government. Although the government would fail, the election of an Islamist to the highest seat in the land served to legitimize the movement. From 2000 to 2012, three out of four Presidents would be ‘moderate’ Islamist, including the current President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud.

The way forward

The current situation in Somalia is unsustainable. AMISOM cannot forever police the Southern regions of the country and, sooner or later, they will have to leave, but they should not leave until: 1) Al-Shabaab is completely defeated (as opposed to providing their ‘nationalist’ elements amnesty as President Mohamud is reportedly considering), 2) the warring clans are disarmed, 3) an inclusive national army is formed and 4) genuine national reconciliation takes place. If this does not happen, Somalia will continue being the chaotic failed state it has been for the past two decades, ultimately ensuring the balkanization of the country.

The Somali people are sick and tired of empty promises and continual failed governments. A growing number of them are beginning to realize that politics and religion simply do not mix. As history has shown, when governments try to mix the two, the constitution goes out of the window. President Mohamud, much like his ally President Mohamed Morsi of Egypt, has shown this to be true. Instead of opting for a government of inclusion and national unity, he has allowed the narrow views of his religious party, The New Blood Islamists ( Damul Jadiid), to hijack Villa Somalia and dictate the decision-making of the government. Now some fear that, like Morsi, he will soon move to grant himself unprecedented powers.

The only way to solve Somalia’s problems, and to prevent a repeat of 1992 and 2011, is to establish a democratic government that respects and protects the constitution and is accountable to its people. In order for Somalia to move forward, democracy and fair and free elections must reign in Somalia. The successive Islamist governments have not been elected by the people but have been installed through corruption and vote-buying assisted by Arab donors from the Gulf states and all have used their time in office to benefit their respective Islamic parties. After twenty-one years under a military dictatorship and another twenty-one years of anarchy, it’s safe to say that the current generation of Somalis are not accustomed with democratic values and principles. A terror-free Somalia should have been the legacy of the U.N. mission in Somalia but now it’s left up to AMISOM to finish what UNOSOM and UNITAF started. AMISOM’s legacy must be the end of the evil scourge of terrorism in Somalia and the promotion of good governance and democratic ideals in the country.

By Zainab Guleed

Email: z.guleed@dissidentnation.com