Towards Building 21st Century Mines

|

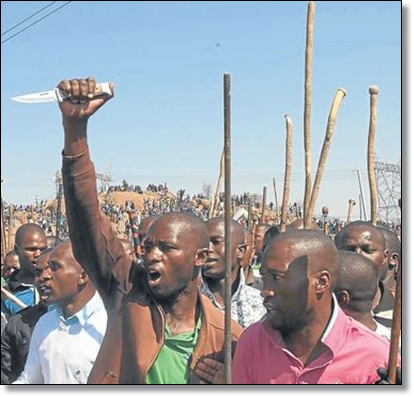

| Marikana miners strike, South Africa P. Courtesy |

Elite pacts that have underpinned most mining licence agreements across the globe are being challenged by local communities and civil society actors. Greater transparency is being demanded about the nature of the agreements, benefit sharing arrangements, environmental impact assessments and management of the mining footprints on ecological systems.

The proverbial resource curse has continued to plague most emerging economies where political elites are seen to be the sole beneficiaries of non-transparent licensing arrangements with industry players. Extractive industry approaches are often inextricably linked to extractive political systems driven by patronage networks that take home the greatest spoils. In such circumstances higher royalties and taxes do not necessarily benefit ordinary citizens who continue to live in grinding poverty. Post-colonial Africa has more than its fair share of countries caught up in the vicious cycle of the extractive industry mode in mining and other natural resources. Nigeria, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Angola and now increasingly my own South Africa are showing signs and symptoms of the resource curse.

Inclusive economic and political systems focus on institutions that emphasise meritocracy and promote the contributions of the best talents and creativity of their citizens to increase productivity and generate a sense of shared value in resources. Unfortunately, South Africa has sustained an extractive economic system that started with mining and energy companies, but now includes monopolies in many other sectors including many serviced by large and powerful – and not necessary – very efficient parastatals.

The experience of the black economic empowerment programme demonstrates how this extractive economic system has seduced new black elites to become part of the closed patronage system. Very few BEE deals have really achieved what they set out to do – namely empower the many and not the few. If we could go back to the drawing board, I would make employees the largest beneficiaries together with neighbouring communities as well as communities in labour sending areas that provide the mines with their manpower.

South Africa is also increasingly finding itself in a very difficult position that reflects all the symptoms of the Dutch Disease. The huge export revenues we enjoyed at the top of the resource super cycle pushed up our exchange rate and rendered our agriculture, textile and other industrial sectors increasingly uncompetitive. The failure of successive post-apartheid governments to invest in, and manage the creation of high quality education and training systems to enhance productivity, has led to a classical unsustainable economic base.

The shrinking economic cake alongside the rising tide of higher expectations that freedom would deliver better material conditions has raised the risk profile of the country. The tragic events in Marikana and protests by agricultural sector workers in the fruit and wine farms in DeDoorns in the Western Cape are a wake-up call alerting South Africans to the many time bombs waiting to go off.

A turnaround is possible. It must start with difficult conversations between leaders of the government, mining industry, and worker representatives. The government must commit to creating an environment of: policy certainty, higher quality physical and social infrastructure, including education for the 21st century, and transparent fair regulatory systems to enable investors to commit long-term resources. The adoption of the first ever National Development Plan by the government is a promising starting point. Success will depend on the implementation of the commitments made to focus more intently on fighting poverty and creating a more positive investment climate with appropriate incentives for both domestic and international investors.

The mining houses and the government must accept primary responsibility for addressing the legacy of the extractive industry mode of mining: the triple burden of silicosis, HIV/AIDS, acid mine drainage, dusty and uranium contaminated environments. Industry led Public/Private Partnership arrangements must be struck to enable comprehensive holistic solutions to emerge. Government must provide incentives for the mining industry to invest in clean up operations which would also provide alternative livelihoods and jobs for ex-mine workers and local communities. Investors would also have to refocus their mindsets away from the short-termism that has driven the extractive industry mode. There is an urgent need to realign the time horizons of expectations of high returns with the unavoidable longer term horizons of the build up process of projects in this capital intensive industry.

Workers representatives and unions must shift their mindset from short-termism to focus more on sustainable livelihoods and higher productivity to enhance returns for everyone. A greater emphasis on demanding higher quality education and training as well as wellness for their members should be the primary focus. Unions have dropped the ball with respect of fighting for proper housing, promoting healthier families and conducive environments for work-life balance for workers. The distance that has developed between workers and their representatives is a key factor in the recent wildcat strikes and tragedies in the mining industry in South Africa. Union leaders are perceived to have become part of the elite with a focus on consumption and status for themselves.

What this requires is that companies continue to create shared value for communities, governments and other key stakeholders in the areas they operate, building on what has already been achieved. This means that mining houses must:

- Build on sustainable local economic development programmes

- Enhance programs focused on the procurement of local goods and services and promote responsible supply chain management

- Work with government to ensure community programmes align and support government development strategies

- Develop sustainable community infrastructure and other projects in collaboration with local communities, government and other key stakeholders

- Respect human rights

- Monitor and optimise stakeholder engagement

Finally and perhaps most critically we will all have to accept the fact that the traditional way of mining in South Africa with its reliance on cheap, low skilled and plentiful labour is over. It is not sustainable. The labour intensive nature of South African mining has deterred investment and the longer government structures its regulations around this model the longer investors will stay away.

How does One Escape the Trap and Build the Future?

I would like to share Gunter Pauli’s ideas informed by his work in Colombia which can be adapted to any other country:

“This possible solution operates within the free market philosophy. However, the future relies on a fundamental change of the mining business model which evolves from a core business centered around a core competence, to a clustering of activities that exploits all available local resources, generating multiple benefits for the mining companies, its industrial partners, the local communities and even the environment. This clustered approach ensures that the Dutch Disease will not smite the commodity trading countries. On the contrary, the design of a new business model for mining ensures that the whole economy regains competitiveness, including the farming and (manufacturing) industries which have already faced a downturn."

Clustering of Mining, Agriculture and Manufacturing Industry

A shift in the business model for mining provides a chance to reverse this trend of deindustrialization in commodity exporting countries. In order to accelerate its effectiveness, it is ideally combined with a shift in taxation policies. As long as mining companies remain core businesses focussed on extracting more ounces from the Earth, and ship these out of the country at lower costs paying a fixed percentage as tax to the government on each unit exported, then there is no solution.

However, if we rethink the activities of the extractive industries and how these could be redirected to respond to both global and local demand, maintaining a focus on minerals, while ensuring an effective use of all opportunities made possible by the mining boom, then there is a future for agriculture and local industries. If the government were to recognize the tremendous potential of this multiplier effect, then a smart shift in taxation can steer mining towards the clustering of productive activities. Mining and the commodity trade will then turn into a catalyst of local economic development instead of being a cause of de-industrialization and rural poverty.

Mining and Basic Needs

Let us take a gold mine as a case in point. Just about every goldmine in the world needs water to process ore. Actually, most mines require water and seldom find abundance in their area of influence. The traditional response of the mining engineers has been to pump water from aquifers, to pipe water over long distances, or to install reverse osmosis facilities if there is salt water in close proximity. These are major infrastructural adjustments, increasing both capital and operational expenses of the mine at a cost of water per cubic meter that the local population would never be able to afford.

Time to think different. While not all regions in the world can provide lasting solutions exactly like the one described below, most mining zones can undergo a major regeneration of native vegetation, or a reforestation in order to turn the hydrological cycles from excessive water consumption by mines and perceived drought and contamination of water to abundance of water for private, agricultural and industrial consumption. Since five to eight years will span the discovery of a commodity to mine and its commercial exploitation, there is enough time to reverse the water supply in the region using all available resources.

Convert Cost into Revenue

If we were only considering the regeneration of forests for the purpose of water, then this represents a cost. This still reduces capital and operational expenses of the mine, since water production and filtration by a natural forest remains cheaper than installing water catchment areas and water treatment systems. However in the business philosophy of the Blue Economy, we are not only interested in merely reducing expenses, we are keen on increasing revenues, not just for the company concerned, but for the local economy. A mining project in the Colombian Andes offers the opportunity to regenerate part of the bamboo forest that once reigned the region. Bamboo, especially giant bamboo (Guadua angustifolia) is well known for its capacity to regenerate water cycles, purifying contaminated water, while regenerating top soil and increasing rainfall since a bamboo cover of the land decreases the surface temperature and therefore increases precipitation.

From Extractive to Inclusive Mining Model

My experience of growing up in a rural area, operating as an activist in a hostile environment of the apartheid regime and being a witness to, and participating in efforts to build a post-apartheid inclusive society, has taught me that almost every challenge can be turned into an opportunity for

change. I have benefitted enormously from turning the hardships of my life journey into learning opportunities. The question for the mining industry today is how we are to turn the challenges we face into opportunities for creative fresh starts?

The mining industry in South Africa has no choice but to make a fresh start. Fortunately many are already working together to develop alternative models to tackle common problems such as the TB/Silica and HIV/AIDs Industry-led effort (The Chamber of Mines with Gold Fields, Anglo Ashanti, and some platinum companies taking the lead) supported by the National Department of Health and international development partners. But much more boldness is needed to develop the “clustering model” that Gunter Pauli refers to above.

Just imagine turning Rustenburg, in North West Province, into a modern mining town with a cluster of appropriate industries that form the supply chain of the platinum mines in the area. Imagine the human and intellectual capital that can be generated through the construction of both physical and social infrastructure to create a buzzing town housing all levels of employees working on neighbouring mines and industries.

Imagine turning the ugly landscape of mining shafts into green spaces that provide agri-business jobs for locals and feeds the households in the area and beyond. Imagine the government, private sector and citizens working together in a transparent way to build a sustainable future together.

But legacy issues in labour sending areas have to also be addressed. Imagine the Eastern Cape and Kwa-Zulu Natal becoming the bread baskets of the mining industry as part of its supply chain for food and other agricultural inputs. Imagine the potential of clustering agribusinesses in these provinces and enhancing the country’s food security as well as its export potential. Gold Fields and Anglo Ashanti are putting together just such an experiment with a chicken value chain in the Eastern Cape. Imagine the growing social capital of rural areas that could follow the termination of the destructive migrant labour model that has damaged rural family life. Imagine the return of these provinces to proud producers of high quality school graduates feeding into a rejuvenated higher education and training system.

All this is possible, but it will take a willingness to take risks and engage in tough conversations between the government, private sector, workers and civil society. It is possible to leverage the mineral resource wealth into a catalyst for re-industrialization of our country, continent and other parts of the world. But we must heed Einstein’s words – we cannot solve today’s problems by using the same thinking that created them in the first instance. Are you ready for change?

By Mamphela Ramphele

The author is Chairperson of Goldfields Limited. She is also an academic, businesswoman and medical doctor and was an anti-apartheid activist.