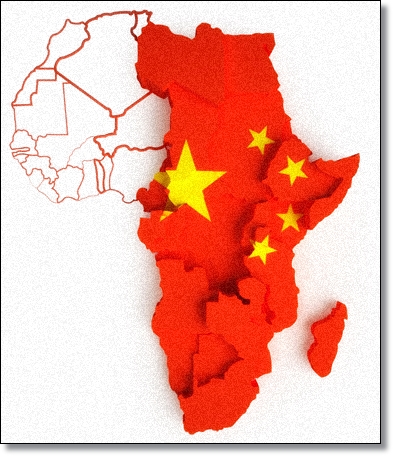

China-Africa: The Psychology and Sociology of Chinese Investment

|

Until the dragon gives its investment policies and approaches in Africa a sociological eye, it will soon be ripe for such high level investments to diminish in value to the average African. Africa is not a country but a continent with varying sociological dynamics. Therefore, the dragon ought to design its investments strategically in Africa. Only then can its sociology be said to be psychologically balanced.

Owing to either the disjointed nature or the magnitude of their investment, it has been very difficult to precisely track or quantify the volume, allocation and composition of aid provided by donor countries especially from the West to Africa. Conversely though, China from among the six largest non-Paris club bilateral creditors to LICs is today the largest creditor to Africa. Amidst Western criticism of Chinese aid to Africa on the grounds of ‘free riding’ inaction in human rights protection and corruption, the rise of China as a very visible actor in Africa is one of the most striking features of the first decade of the new millennium, that we should conjointly celebrate.

China’s critics view China primarily as a competitor unburdened by the kind of social, environmental, and governance standards increasingly applied to finance from the West. Western media dresses China as a new donor in Africa, rocketing to a position of prominence, without morals and mainly engaged with rogue regimes and resource rich countries. For the purpose of this piece, although trade and investment are two central means by which China and Africa engages, my primary focus will be on the sociology of development finance and official development assistance: the broad spectrum of activities called “foreign aid.” The hypothesis of my “Investment Diplomacy” article seeks to fill an important gap by explaining and analyzing the Chinese sociological system of aid and development finance, with the aim of asking whether such Chinese foreign aid is actually helping to improve particularly Africa’s debt and investment climate. Its purpose is not to take sides in the many debates over these issues, but to inform transatlantic discussions about China’s role as a development actor in Africa. I hope to speak to sociologists, policymakers and others concerned about development and poverty in Africa to better understand the nature of China’s impact as a donor, thereby contributing to transatlantic efforts to develop constructive approaches in engaging China as a newly prominent feature of the evolving aid architecture.

Contextualizing China’s Aid Sociology and Diplomacy in Africa

Like any other emerging or dominant economy, China gives aid for a variety of reasons: as a political tool of foreign policy and in support of its own economic interests; as a response to domestic stakeholders, and as a reflection of higher values and principles. As a tool of foreign policy, aid is critical in support of the “one-China” policy. Aid also acts to smooth the way for other economic transactions (exports, investment, and construction contracts) and it reflects China’s vision of itself as a responsible, significant power, quick to deliver humanitarian assistance. To what extent has this dream been achieved in Africa? While such aid policy approach towards Africa may not be stainless, it somehow appears to be strictly in conformity with the five principles of the Chinese foreign policy which to their credit has maintained socio-economic and political stability between the multi-culturally complex countries of Africa and one country, China.

While China’s aid package for Africa grows to the enviable tune of hundreds of billion loan and investments, China maintains respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of her fellow sister African countries, a non-interference/aggression, equality and win-win regardless of demography and above all peaceful co-existence from an economic interdependent perspective. Such foreign policy consistency backed by tangible investments and ‘unconditioned’ loan for African economies will unquestionably help improve development and sustainability issues in Africa. Again these virtues of the Chinese approach especially in debt cancellation, critics maintain, lowers standards, undermines democratic institutions and increases corruption, particularly in oil-rich countries that suffer traditionally from such resource curse.

My question remains: Is this a balance criticism of Chinese investments in Africa? Assuming the response is in the affirmative, hasn’t Africa equally seen worse excesses of the so-called democratic tenets? Have we as a continent sat down to ‘retreat’ on how and why we today have civil and political conflicts in countries practicing democracy? What will you critics say about China’s debt sustainability, for example, which has seen export and income growth in Angola and Sudan? Both countries have seen rapid export and income growth in the present decade. While Angola has an export share of 84%, Sudan is more ‘closed’ with a share of 23%.

Merits of a Sino-African Romance

Political economists the world over have maintained that market competition is key in enhancing domestic socio-economic stability and development. For example, China’s four summit meetings with African leaders (2000 in Beijing, 2003 in Ethiopia, 2006, and 2012 in Beijing) sparked the European Union to organize an EU–Africa summit in December 2007, its first in more than seven years. Universities and institutes in Europe and the United States have convened dozens of transatlantic conferences on China and Africa. Such competition for African markets will (if managed properly) contribute to export and income growth. The West need to take blame for their apparent loss of grip on Africa, because it is their share neglect on the guise of independence that saw the heightened interest from China who has invested over $100billion in Africa.

China is not only giving unconditional loans, but has taken giant steps in cancelling debts of most African countries. China has cancelled millions of debt and waived duties on exports in many African countries, awarded over 2000 scholarships to African students. As part of its outreach to Africa, China is also active in national security assistance programs, selling arms mostly to Sudan, Nigeria and Zimbabwe. Beijing’s assistance to African states in this context is ostensibly to enhance the capacity of these countries to maintain internal security. However, China’s arms sales to Sudan and Zimbabwe have been a cause for concern given the volatile political situations in these countries. Moreover, China has contributed to international peacekeeping operations in Africa, where it has more than 1,300 soldiers deployed in Liberia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Southern Sudan.

To conclude, like the structural functionalist Comte would emphasize, we want to maintain that regardless of the billions of dollars the dragon invests in Africa, sincere consideration should be given to the sociological make up of Africa as a continent and not the reverse where it’s like between two independent countries. All the basic units that makes up the African continent should be allowed to romance with China separately and not a one policy approach for all 53 states.

By John Juana

Lecturer, Njala University, Sierra Leone.