Education: Why Mother Tongue Must Be Embraced

|

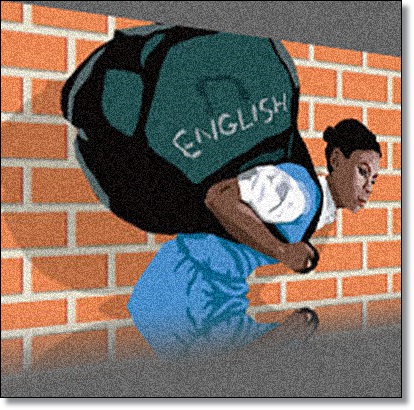

| Are foreign languages a burden? P. courtesy |

This was part of the news bulletin on Tuesday, April 8th, 2014. It was an assertion by the government that children in lower primary classes in Kenya will be taught in their mother tongues (or the dominant language of the region). An assertion which, as before, is expected to see reactions from both supporters and opponents of the issue at stake.

I am a strong supporter of teaching children in their mother tongue. I am a product of the policy, and can now speak fluently and proficiently read and write in my mother tongue, Gikuyu, and do the same for English and Kiswahili, and to a mild proficiency, French. But I am not about to throw stones at those opposing the move. When parents and teachers rise up in arms crying out that their children are disadvantaged when they learn in their mother tongues, we have to listen and ask why.

Societies across the world have grappled with the issue of language policies for a long time, and many scholars have researched on the roles of language in society at length. Bourdieu (1991) introduced the concepts “cultural capital” and “linguistic capital”, whereby “linguistic capital” is a part of the larger “cultural capitalAccording to Bourdieu, language is “a kind of wealth” (p. 43) in society.

Bourdieu argued that in every society, there are “linguistic markets” that are determined by possession of a particular language or language variety. Possession of a particular language might offer more opportunities for people in terms of getting jobs and upward social and economic mobility. In many of the post-colonial African countries for instance, the former European languages are still used as the official languages, even after independence from the colonial powers. English continues to be used in much of the former British colonies, now commonly referred to as the Anglo-phone Africa, while French dominates the former colonial countries, now the Franco-phone Africa. In a few former Portuguese colonies, the Lugo-phone Africa, Portuguese is the main official language. Notably, possession of these former colonial languages has continued to be associated with power, and to succeed in school, students must be proficient in these languages (e.g. Bokamba 1991, Bagmbose 1991).

This is why we must understand those that are opposed to the use of the mother tongue in school in Kenya. We are a product of colonialism and its linguistic imperialism, and delaying learning the English language in school implies, to many, lagging behind in the acquisition of this cultural/ linguistic capital that is important for social-economic upward mobility. But is that necessarily the case? You might ask. The quick answer is ‘No.’

Research has shown that a child’s first language actually facilitates, rather than hinders, learning. I have deliberately ‘borrowed’ the title to this article from the interview published in the “Conversations with book lovers” section of the Daily Nation dated February 1st, 2014, with Professor Duncan Okoth Okombo of Nairobi University. This is why I totally agree with the views expressed therein-- not because Professor Okoth-Okombo is one of my favorite former professors, one among those who initiated me into the world of Linguistics - that field defined as the “Scientific study of language”!

As professor Okoth-Okombo mentioned in his interview, research shows that it is possible to transfer knowledge- linguistic or content, from the first language to the second. In fact, children who gain their knowledge in their dominant first language will tend to out-perform those who are immersed in a second language learning environment. Cummins (2000), for instance, talked of the interdependence hypothesis based on the observation that “academic language proficiency transfers across languages such that students who have developed literacy in their L1 will tend to make stronger progress in acquiring literacy in L2” (p. 173). (In linguistic lingo, L1 and L2 refer to first and second languages respectively). Based on this premise, Cummins recommended that educators of second-language learners should promote the use of the children’s L1 while they are still acquiring their L2.

Elsewhere, scholars have referred to the concept of “swim or sink,” whereby learners are left to fight it out in a strange and foreign linguistic environment in school. While some manage to ‘swim’ and succeed, many, however, ‘sink’ and perish from the education system. Is it a wonder, then, that today we are talking of about a quarter of a million Kenyan children who cannot go on to achieve a secondary education because they have “failed”? Unfortunately, we are a nation that celebrates a few that “swim” across and quickly forgets the many who “sink” along the way. While we cannot claim that language is the sole cause of massive failures in our national examinations, we can comfortably rely on what research has showed elsewhere. Language, without a doubt, plays a major part in the performance of these exams.

May be if more of us get educated on the effects of the mother tongue in the learning process this debate might become more meaningful. Professor Okoth-Okombo provided some good examples, and here I cite one more case.

Two researchers, Bloch & Alexander (2003), conducted a project at Battswood primary school in S. Africa- a school that was designated as ‘colored’ during the apartheid era. Initially, Afrikaans was the main school language but over time English became the main medium. The researchers noted that the majority of the children were native Xhosa-speakers, with smaller numbers of Afrikaans and English-speakers. They further noted that the children were performing poorly in school. In their approach, Bloch & Alexander (2003) argued that one of their guiding principles was to view language as a ‘resource’ rather than a ‘problem.’ They therefore put emphasis on the children’s native language, i.e. Xhosa, and encouraged the teachers to use the L1 with the children in the classroom, while also teaching English. With time, the children demonstrated a rich progression of literacy skills in both languages, i.e. Xhosa and English. Like other similar studies, this project revealed the importance of children’s L1 in developing literacy skills as well as a second language.

Many children in our society get excited to go to school on their first day, only to find themselves in a foreign environment, compounded by a foreign language. A sudden disconnect occurs between home and school, and many children get confused. Many parents, especially in the rural areas, do not know what goes on in the school because they do not feel like they belong there. When the parents do not speak English, they become estranged to their children’s learning process. Yet, parents need to be fully engaged in the learning of their children, whether they speak English or not. Children’s homes form a part of “funds of knowledge” (Gonzalez, N., Moll, L., & Amanti, C. (eds) (2005), which facilitate a child’s learning in the classroom. A child’s mother tongue is a major part these “funds of knowledge.”

What more? Our mother tongues are important not only for academic success, but also for general personal growth. Language is a strong marker of self identity and a source of self esteem. Many young adults who have grown up in the metropolitan cities like Nairobi, where they acquired only English and/or Kiswahili as their L1, confess to the feeling of inadequacy for lack of their mother tongue. Many are those who, sadly, cannot communicate with their grandparents.

This debate reminds us- once more -what the colonial era did to us psychologically. We argue that there is little to come out of learning through our mother tongues. We believe that it is only in English that we can gain knowledge. We continue to equate knowledge of English with intelligence, which it is not. And as Professor Okoth-Okombo pointed out, only in these regions of the world do we continue to clamor for an Education that is conducted in another’s tongue.

For the good of our children and society in general, let us support the policy to teach them in our mother tongues. For this to happen, however, all stake-holders must be brought on-board and be assured that by the time their children sit their K.C.P.E., they will be well-prepared to perform in the English-based examination. That in fact, they could turn out to be better performers than those who are taught in English from Standard 1.

And there lies the catch. For parents and teachers to support this policy, they too must be well educated on the benefits of a first language. Rather than look at our mother tongues as a problem, we need to view them as a great resource in the learning and personal development process.

By Dr. Margaret W. Njeru

The author mwnjeru@gmail.com is Senior Lecturer, School of Education, Riara University, Kenya.

References

Bamgbose, A. (1991): Language and the nation: the language question in sub-Saharan Africa. Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press.

Bloch, C., and Alexander, N. (2003). A Luta continua!: The relevance of the continua of biliteracy to South African multilingual schools. In N.H. Hornberger (Ed.), Continua of Biliteracy: An ecological framework for educational policy, research, and practice in multilingual settings. Buffalo; Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Bokamba, E.G. (1991): French Colonial Language Policies in Africa and their Legacies. In D.F.Marshall (ed). Language Planning: Focusschrift in honor of Joshua Fishman. Philadelphia, John Benjamins publishing company.

Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and symbolic power. Oxford, U.K., Polity.

Cummins, J. (2000). Language, Power and Pedagogy: Bilingual children in the crossfire. Clevedon, Multilingual matters Ltd.

Gonzalez, N., Moll, L., & Amanti, C. (eds) (2005). Introduction: Theorizing Practices. In N. Gonzalez, L. Moll & C. Amant(eds.) (2005). Funds of Knowledge: Theorizing Practices in households, communities, and classrooms (pp 1-28). London, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.