Somalia:State of Maternal Health

Maternal and child healthcare is the most precious right of citizens, a moral obligation of the State and the best buy for development

The 1991 civil war in Somalia has led to a state collapse and persisting civil conflicts, a period constituting the darkest pages in the history of the country, since the period of colonization, extracting a heavy toll on the people’s security and livelihood. In the ensuing two decades or more of turmoil, the world has been witnessing the legacies of one of the most important summits, where the heads of states and governments of 189 countries attended a Summit on the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) held in New York in September 2000.

In this gathering, the human values of freedom, equity, solidarity, peace and security, tolerance, poverty reduction, halting discrimination against women, shared responsibility and development advancement were deliberated. The summit outlined eight goals that the humanity has to strive for and attain ranging from halving extreme poverty, providing universal primary education, generating significant reduction in maternal and child mortalities and combatting HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis and other diseases. The Millennium Declaration has galvanized a global race for achieving the MDGs by the set target date of 2015.

How close is the world to Achieving the Health MDGs?

Over the past two decades the world has made significant gains in achieving the maternal and child health MDGs. The target was to reduce child mortality by two thirds and maternal mortality by three quarters by 2015, considering the 1990 mortality conditions of each country as its baseline. Since 1990, global maternal deaths have been reduced from 400 to 210 for every 100,000 live births with a reduction rate of 47%. Likewise, the mortality in children under-five dropped by 41%, from 87 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1990 to 51 in 2011, cutting the child deaths from 12 million in 1990 to 7.6 million in 2010, despite the enormous population growth. Nevertheless, the world is yet short of achieving the maternal and child health related MDGs set for 2015. In fact, WHO reports that globally, a woman dies every two minutes from pregnancy related complications with poor survival chances for the newborn, while for every maternal death, 20-30 other women suffer from lifelong health problems consequent to their pregnancy.

The Current State of Somalia's Health Status. Measuring Performance from Maternal and Child Health Related MDGs

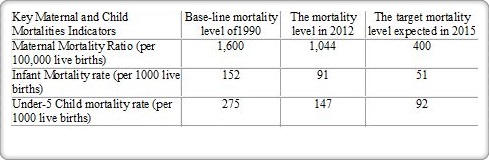

The health status of a nation can be measured by its maternal and child survival conditions. Accordingly, the health improvements achieved by nations can be monitored from its progress towards achieving the health MDGs. The table below shows the slow progress made by Somalia.

Table 1. The slow progress in health MDGs reflecting the poor state of maternal and child health in Somalia

|

These results should indeed ring alarm bells illustrating that Somalia is one of the countries with the slowest pace in the world with regard to its maternal and child survival conditions. If this does not yet serve as a wakeup call, the situation will deteriorate further. Moreover, if the same slow pace is sustained in the future, the country will achieve its maternal MDG target after 26 years or not earlier than 2040, while the infant and under-5 children related MDG targets will be reached after 15 and 10 years, or not earlier than 2029 and 2024 respectively. The majority of the world is prepared to achieve these targets by 2015 or shortly thereafter and embark on the post 2015 agenda outlined by the World Health Assembly of 2014. Accordingly, the Somali leaders and policy makers at every level will need to scale up maternal and child survival interventions, declare them an emergency and assign the highest priority to them in the public health sector.

Somalia the Toughest Place to be Mothers

Save the Children Fund, an international non-governmental organization (iNGO) promoting children's rights and providing support to children in developing countries produces a yearly global report on the state of the world’s mothers. The report ranks the countries according to their maternal health status from those qualifying to be the best or the worst places in which to be a mother. This is a composite indicator based on data on maternal and child survival, together with education, income and political representation of women. In the 2014 report, Somalia ranked at the bottom out of 178 counties, qualifying to be the toughest place to be a mother. The figure below illustrates this gloomy finding, reflecting the gravity of this situation. Moreover, the report also outlined that “Somalia has the world’s highest first-day death rate of new-borns (18 per 1,000 live births).” It is also one of the countries with the highest lifetime risk of death in the world, where one woman in 16 is likely to die in pregnancy or childbirth. Looking on child mortality data, Somalia is also one of most difficult places in the world for a child to survive and reach the age of five years.

Table 2. State of the World’s Mothers: the best and the worst Places to be a Mother

|

A call for Action:

To reverse the situation of the current high maternal and child mortalities, the Somali top leadership at federal, state, regional and local level need to rise to the occasion and mobilize resources, people and action to contain this recurrent and ongoing tragedy. The health system has to prioritize maternal and child health care, develop concrete and doable strategies, and take tangible steps for its implementation, as this constitutes a real visible measure and proof that attention is being directed to their survival and wellbeing. The following are some key operational steps for the effective pursuit of this mission:

-

Service delivery: offering universal access to maternal, neonatal and child health care

-

Equitable access to quality health care by bridging both the gap and disparities between urban and rural/nomadic population and ensuring universal access to the essential package of health services (EPHS)

-

Delivering essential health services at the community level where health promotion, disease prevention and basic care is offered to mothers and children at their door steps through the recently launched Female Community Based Health workers’ (FCHWs) programme

-

Organizing health facilities in all sub-district localities and villages that have a population of 2,000 or more, providing basic emergency obstetric care (BEmOC) and child care services with the imperative deployment of trained community midwives or assistant community midwives

-

Instituting in every regional hospital and at least in one additional district hospital from the same region, comprehensive emergency obstetric care (CEmOC) services where Caesarean Section Operations are effectively carried out, with readily available blood transfusion services in which all high risk pregnancies receive the quality of care they need

-

Ensure the early referral of high risk mothers residing in distant districts and rural settings where travel by car takes more than two hours, in which high risk pregnancies are temporarily relocated for additional antenatal care (ANC) and to promptly access CEmOC during labour that include caesarean surgery and blood transfusion in the case of need

-

Creation of waiting homes for the relocated high risk pregnancies that host these mothers for up to 30 days before their due date of labour, organized by the regional and district governments in coordination with the regional/district health officer

-

Ensuring that pregnant mothers receive at least one but preferably three or more ANC visits by skilled health workers and skilled birth attendance during labour

-

Encouraging families and mothers to practise child spacing to enhance maternal and child health and reduce the risk of maternal complications or mortality

-

Promoting adequate nutrition through first six months’ exclusive breastfeeding, complementary feeding and weaning, establishing therapeutic feeding centres to manage the severely malnourished and improving water and sanitation facilities, and hygiene practices in all community settings

-

Implementing integrated health interventions that incorporate vaccinations, vitamin A supplementation and de-worming as well as using long-lasting insecticide-treated nets (LLINs) in high malaria endemic districts

Addressing the shortage of skilled health workers

-

Training and deploying health professionals, particularly the midlevel health workers such as nurses and midwives/community midwives in all facilities and assistant community midwives at the grass root community level

-

Training and deploying Female Community Health Workers (FCHWs) at the community grassroots level in remote localities and villages to offer basic primary health care services with focus on maternal and child health

-

Imparting adequate knowledge, skills and behaviour change training to traditional birth attendants (TBAs) who are often the only source for assisting deliveries in communities living in underserved areas, and enable them to recognize the high risk pregnancies for their timely referral, while safely assisting normal deliveries

-

Ensuring the regular provision of essential commodities and medicines such as ORS, zinc, amoxicillin Iron/folate supplementation for all pregnant women, vitamin A supplementation for all children above six months and under-five years of age, routinely delivered vaccines with availability of basic equipment

Ensuring adequate health financing

-

Scaling up the health and nutrition programme support jointly financed by development partners to enable the expansion of the EPHS programme in the country with special focus on maternal and child health care

-

Scaling up the central, state, region and local government financing support to maternal and child health with focus on disadvantaged and remote population groups and localitie

-

Organizing Diaspora support for the establishment of health centers and MCH facilities and to finance the training of community midwives, assistant community midwives and FCHWs in different districts of the country

-

Creating community financing schemes in support for the work of FCHWs and the government to establish voucher schemes to encourage free ANC visits and facility based delivery with compensated transportation costs, with especial care to the referred high risk pregnant women, thus ensuring an unimpeded universal access to CEmOC services

-

Creating supportive environment for mothers and children

-

Eliminating all types of violence and abuse against women and girls including female genital mutilation and child marriage

-

Promoting girls’ education as this will have a significant positive impact on maternal and child health

Conclusion

The national authorities and the people of Somalia should react sharply and positively to the findings of the Save the Children Fund 2014 global report, in which the health of Somali mothers was ranked at the bottom of the world, with a view to reverse the current trends. There is need for Somalia to transform from being the toughest and worst place to be a mother, to a country that protects the rights of its mothers and children and is ready to offer quality health services and protection that they need. The Somali leaders should know that they are essentially responsible for the excess mortality of thousands of mothers and tens of thousands of young children annually from simple and easily preventable health conditions. Maternal and child survival requires actions within and beyond the health sector, which makes it imperative for the government, health professionals and the people to join hands and rise to the occasion and address the current appalling facts on a war footing, and speed up progress towards achieving the universal maternal and child survival goals.

By Prof Khalif Bile Mohamud

Email: drbile@yahoo.com