Breathing Life Into Lake Victoria

|

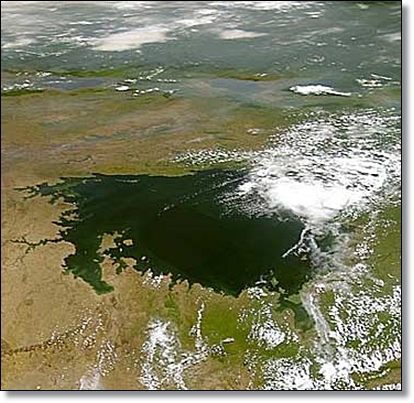

| Satellite image of Lake Victoria |

He adds that the resumption of Tin mining in the area which had closed down in the 1970s has led to the development of big stone quarries. Floods always wash away the opened soils from stone quarries to river Kagera.

According to a Senior production manager working in one of the vegetable oil industries In Mwanza region, Tanzania, “Most industries you see here are unplanned and uncontrolled, and most of them including the big ones don’t have waste management mechanisms. They discharge their untreated effluents into Lake Victoria, contributing to the industrial pollution of the Lake.”

Most chemical industries located in cities and towns along the shores of Lake Victoria such as Mwanza, Kisumu and Jinja, among others, are not connected to their central national sewerage systems and are unabatedly continuing to discharge their raw effluent into the Lake, with East African governments, and organizations such as, Lake Victoria Environmental management programme (LVEMP), Lake Victoria Fisheries Organisation (LVFO), National Environment management Authorities, and National water and sewerage corporations doing very little to abate the situation.

The Lakes’ ecological, fishery, water, and biodiversity resources, are also being destroyed by agricultural and mining pollution emanating from poor farming practices and artisanal mining activities in areas such as Geita and Musoma, in the Lake basin. Most farmers along the Lake basin and those living in its catchment areas regularly use organic pesticides and fertilizers to protect their crops and improve soil fertility. Some even use organochlorine pesticides such as dieldrin and aldrin which are very toxic to fish, fish breeding grounds and people’s health.

Most wetlands along major rivers such as Kagera, Nzoia, Mara, and Sondu- Miriu, which are the four major catchment runoff areas that feed water into Victoria are fast diminishing, as people encroach on them for agricultural and settlement purposes, meaning that, they are no longer acting as buffering strips. Water that is not properly filtered is thus being discharged into the Lake with excessive pollutants, leading to deteriorating water quality in the lake with catastrophic effect on the fish composition and catch, household incomes and livelihood standards of fishing communities. Many fishermen consequently engage in fishing immature fish, using illegal fishing gears, in a desperate move to make ends meet, leading to declining fish catch and possible extinction of some fish species.

Lake victoria, the second largest fresh water in the world, continues to be a key resource for riparian countries, through provision of food and water for various uses (industrial, agriculture, livestock, tourism, bio diversity conservation, and recreation). Export earnings from the lake amount to above US $400 million. The lake also supports the livelihood of over 30 million people. Why isn’t this key resource sustainably conserved? What is the problem at hand?

Tanzania, Uganda and Kenya, which principally share the lake, have a major responsibility of conserving it through their responsible established ministries. Since the lake’s total catchment area also includes Rwanda and Burundi, where river Kagera originates from, there is need for these five countries to come up with comprehensive ecosystem management mechanisms, ably fund organizations like LVEMP, LVFO, NEMAs and NW&SC, and task them to perform their stipulated mandate of conserving the lake through developing and implementing programs such as catchment afforestation, wetlands restoration, water hyacinth control and municipal and industrial waste management, among others.

By Moses Hategeka

The author moseswiseman2000@gmail.com is a Ugandan based independent governance researcher, public affairs analyst, and writer.